#40 NOCLUTCH,NO GEARS,NOFUEL TANK, HOWELECTRICBIKESARE NONOISE,NOFUMES... SHOCKING THEFLATTRACKWORLD

enter 2020 with the invaluable help

input of the following people: John McInnis; all at BlatantMoto; Cory Texter; Sammy Halbert; Sammy Sabedra; Shawn Baer; Eddie & Mark at Zero; Jamie Robinson; all at The One Moto Show; Tim & Bill at H-D Museum; Todd Marella; Prankur Rana; Toria Jaymes; Max & all at HookieCo; Ed Subias; Paul Bryant; Nik Ellwood; Caylee Hankins; George & the piglet photo crew; Scott Toepfer; Geoff Nickless; Leah Tokelove; Katja ‘Kayadaek’; Maxwell Paternoster; Cheetah; Kentaro Yamada; Inuchopper Kei; the Have Fun!! crew; John Harrison; Chris Watson; Tom Bing; Lenny Schuurmans; Sticky; Jason; all at American Flat Track; Anthony Brown & the DTRA; all our advertisers old and new. Support those who support the scene. Thank you for buying Sideburn.

opinions expressed in Sideburn magazine are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the magazine’s publisher or editors.

meets 2020, see why on p25

SIDEBURN

Sideburn is published four times a year by Inman Ink Ltd

Editor: Gary Inman

Deputy editor: Mick Phillips

Art editor: Kar Lee

For advertising/commercial enquiries please email:

©2020 Sideburn magazine

2040-8927

None of this magazine can be reproduced without publisher’s consent

SIDEBURN 41 will be published

May 2020. To subscribe go to sideburn.bigcartel.com

@sideburnmag sideburnmag sideburnmagazine.com We

and

The

1920

sideburnmag@gmail.com

ISSN

sideburnmag@gmail.com

Cover: BlatantMoto Death Rattle and Kim Lohstroh Young Photo: John McInnis

in

IS THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF AMERICAN FLAT TRACK Photo:Cay leeHankins

The Brat 125 eats up the urban terrain and turns it into your own personal amusement park. Designed in the UK by the team at Herald, it has an attitude to match its unique rugged looks. Available in military green, iron grey or copper. #heraldriders DON’T BE anti-social www.heraldmotorcompany.com

#40 issue 6 ENERGY FIELD The inaugural Electric National was was shocking 22 C-TECH New regular racer-tech with Cory ‘C-Tex’ Texter 25 PIGLET Recreating a century old photograph 33 SNOW TIGER Hookie Co’s 1967 Triumph T100R 42 CLASH Leah (above) compares Indian’s pair of hooligans 51 PORTFOLIO The engaging race photography of Geoff Nickless 60 ICE BLUE RACER Have Fun!! Fantic Caballero straight out of Japan 66 BLUE COLLAR BMW Shawn Baer’s F800-based Production Twin 72 PERRIS Southern California’s favourite short track 80 BOLT x EDIE Adventures in moto clothing design. Features rough cider 88 THE RACER’S RACER Jon Bell and his Yamaha 500 93 VESPA RAID MAROC Much like the Dakar but on 10in wheels 100 NBBBS Harley XLR900 can’t cure Next Bike Syndrome 5 Regulars 18 Interview: Anthony Brown 107 Have Fun!! Japanese Flat Track 109 Schuurman’s Backflash 110 Racewear 113 Sideburn merchandise 114 Trophy Queen Illustration: Chris Watson

Energy Field Rider, builder and organiser all report from the first ever Electric National flat track race Words: Jamie Robinson, Brandon Dawson, Thor Drake Photos: Cameron Strand, Erik Jutras, Kyle Hannon, Jason Hansen, Dylan Andrako, Sammy Halbert

Our frontline correspondent Jamie Robinson, no clutch, no noise, and, as it turns out, no chance

7 >

RACER

THE FRONT ROW is tightly packed, bar-to-bar. All eyes are on the starter, waiting for his flag to drop, but it’s so quiet I can hear my own squeaky farts, and the crunching of the chubby kid munching on popcorn in the stadium seats to my right.

A deafening silence has fallen around Portland’s Veterans Memorial Coliseum in anticipation of the first ever Electric National flat track, part of 2020’s One Moto Show. To my left, I have a host of motorcycle pros including Davis Fisher, Andy DiBrino and none other than Slammin’ Sammy Halbert. Halbert is the holder of 13 Grand National victories, a de facto National #1 and someone who has already used me as traction in a heat race earlier in the day.

Prior to this nerve-jangling moment I’ve done four practice laps and nearly got lapped1. Next it was time for the six-lap heat race, and I nearly got lapped. Slammin’ Sammy crashed in turn 1 and he still got back up and beat me into last place. He skilfully slid up to me then slammed into my side, causing me to take a sharp right in this left-handed sport. It was a hard hit, but ‘rubbing is racing’. Still, you could say I’m feeling less than confident about what is to come…

As the starter makes his way towards me, my right wrist begins to twitch in anticipation, but there’s no noise, no vibrations, no toxic fumes to get me high. This is a very real-life Scalextric slot car race, and I’m sat on the joystick. To add to the madness, I don’t have a clutch to drop, or gears to shift, only a throttle to twist and go and brakes to squeeze and stop. Half of what I know about riding a motorcycle is missing, and yet, I’m about to race one.

With a nod of my head to the starter, signalling I’m ready to go, he makes his way down the line shouting, ‘Eight laps!’ What? I thought it was six. I’ll do well not to get lapped. But the flag man has made a mistake and returns, waving his hands and shaking his head. I’m relieved for a split-second until he shouts, ‘No, no, 12 laps! 12 laps!’ My heart sinks. I shout out loud, ‘What? 12 laps?’ The rider next to me quietly says, ‘Yes, 12 laps.’

Up until now, every start line I’ve ever sat, on from being ten years old, has featured deafening, revving engines and vibrations that tingle through you like an electric shock. Usually, just seconds before the start, you can’t hear yourself think, let alone hear someone speak. Now, I’m hearing everything, much of it I don’t want to, and wish I was wearing the same earplugs that I’d laughed at my competitors for using as we geared up. It is all oddly surreal as the starter raises his flag.

I pin the throttle back and wheelspin my way towards turn 1 with a gaggle of other racers. I don’t know if you’ve been concentrating, but there is no ‘VVVRRROOOOMMM! or BBBbrrrraahhHH! Just a ‘WWhhhiiiizzzZZ! And a BBiiiiiZZZZZ! Like a swarm of

(clockwise from top left) BlatantMoto crew meet their rider, Andy DiBrino in The One Moto Show’s exhibition hall the night before the race; Temporary track in Portland’s Veteran Memorial Coliseum; Wet winter clay made track conditions tricky; Organiser, Thor Drake, receives some feedback; DiBrino leading the pack; Road racer Cory West, one of Zero’s entries; Thor is a shovel head; Zeroes for heroes: 69 is Sammy Halbert, on his right is Davis Fisher, 0 is West, 499 is Zero R&D test rider, Trevor Doniak

Appendix

1 Englishman Jamie Robinson is no mug when it comes to racing bikes, he’s a former World Championship Grand Prix 125, 250 and 500 racer and has competed at the Isle of Man TT.

>

aggressive bees around a hive. There’s plenty of argybargy going into turn 1 and I keep well out of it, hoping to pick up the pieces, but no one goes down and my wide line is for nothing. I exit turn 2 dead last. Going into turn 3 a rider goes down on the inside and I have to take avoiding action, more time lost, and as I cross the line to end lap one I’m already nearly half-a-lap down on the leader, and there are still another 11 to go. Oh boy, this is going to be a long race – for me, at least.

I blow corner after corner and waste more time as I try to get used to the Zero’s lightning-quick kick in the on-off powerband, which has nearly spat me over the high-side a few times already.

As the laps wear on and I lose sight of the next rider, a dread fills me. It is only a matter of time before I’m going to be used as traction. This time, before I get whacked, Sammy does me a favour and shouts, ‘Get out of the way!’ And I hear him! I do just that and avoid being used as a berm once again. Not wearing earplugs has come in useful after all.

Despite my own sluggish performance, which lacks spark and is not lightning fast, the Zero electric motorcycle is the total opposite. This thing is zippy, and goes places fast. It doesn’t feel powerful in the same way as a two- or four-stoke motor does, but you can still feel the energy each time you twist the throttle, and that energy surge connects with the rear wheel. No clutch or gears to worry about, just twist and go, and next to no sound or vibration between your legs.

Instead, my hearing is in tune with everything else, like the whizz of the spinning tyre on the moist Oregon dirt, and the clang of the chain as I hammer on the rear brake. For the first time during a race I can even hear the crowd scream, riders yell, and the race commentator jabbering down the mic.

This is undoubtedly a different sensation, because a lot of what I enjoy about riding a motorcycle is now missing – things that I believe add to a fulfilling ride – but the rest is the same: two wheels, a powerplant, and, with a simple twist of the throttle, fun is to be had.

So plug me in and charge me up, as I am all in for electric motorcycles and doing it the greener and cleaner way. And think of the possibilities of where we can now ride… Imagine more indoor motorcycle races, moto parks in residential areas, and more moto events that combine racing with shows.

I’ve had so much fun whizzing around on a dirt oval I could easily have blown my own fuse, and I’m seriously looking forward to my next electric moto experience. But to get the full effect I’ll be making my own brum-brum noises.

JR motogeo.com

If you thought first corners were scary, imagine holding the rider meeting in front of this lot

BUILDER

A DEATH RATTLE is the colloquial name for the noise someone makes as they’re about to die of terminal respiratory secretions. This bike is the death rattle of Alta Motors and it is the sum of so many things we wanted to accomplish during our time at the all-electric motorcycle company founded in 2007 in San Francisco.

The demise of Alta was painful, but it wasn’t without its positives. This bike is one of them. Not widely known, there was an internal effort at Alta to create a tracker based on the Alta Redshift. For numerous and unimportant reasons, this bike never came to be.

After Alta went out of business, we found ourselves without jobs, a surplus of Redshift parts and a bad taste in our mouths about what went unfinished. The three of us (John, Vinnie and I) founded BlatantMoto and set out to create a purpose-built flat tracker. Dale Lineaweaver2 helped us with the frame hard points and we went to work bending and notching tube. We ditched almost everything on the stock Redshift other than the battery and drivetrain. The bike ended up with a 54.5in (1384mm) wheelbase, 25-degree head angle and was more than 30lbs (13.6kg) lighter than it started. Almost as soon as we finished the bike we were invited to be part of the Electric Revolution exhibit at the Peterson Auto Museum in LA. Although honoured, it meant the bike wouldn’t see a race track for a whole year.

While the bike was in the museum, we caught word that Thor was organising an all-electric race class at the One Moto Show. The timing of when the bike was to be released and when the race was being held was tight, but we knew we had to be there. With only one chance to go testing, we reached out to James Monaco3, who was nice enough to invite us to his private track and even set us up with Damon Coca as a test pilot. To finally see the bike’s design intention realised, spinning laps on a proper short track, was awesome. With a few small tweaks to the bike, we were as ready as time allowed.

Andy DiBrino rode the bike at the race, grabbing a flagto-flag win in his heat. To most, winning a heat race isn’t much to write about, but in that moment it was validation of all the hard work started by Alta and carried on by the three of us at BlatantMoto. During the main, Andy nailed the start, breaking out front early and led a couple of laps before getting stood up aggressively by another rider, pushing him off the podium. All in all it was a success; one that we were proud to accomplish.

Our Death Rattle closed the door on Alta and gave birth to BlatantMoto, but, most importantly, it represents a challenge to the motorcycle world for the possibility of what could be next.

BD blatantmoto.com Appendix 2 Flat

track engineer and former Alta employee.

3

Monaco is the former AFT Twins racer who was paralysed in an accident at the penultimate round of the 2019 season. Coca is a 23-year-old California fast guy who has competed in AFT’s GNC2, Singles and Production Twins classes.

ORGANISER

FINALLY, AFTER YEARS and years of talking about ‘Wouldn’t it be cool?’ and ‘Man, I wonder if it would work?’ there are enough electric flat-track-looking race bikes to have a full-grid race. I took notice of this and somehow talked Zero Motorcycles into co-hosting a professional indoor short track race: electric bikes plus nationally recognised riders.

Getting pros to participate wasn’t too hard. Sammy Halbert asked if there was money on the line and I told him, ‘Yes, $1000 in $1 bills.’ He was in. When I asked Davis Fisher if he wanted to race my bike, he said yes without hesitation.

I find it funny that flat trackers by and large are the most accepting of the electric wave, when much of the rest of racing is pretty well consumed by tradition. Try getting a motocrosser on the electric wagon and they will most likely laugh in your face. They usually say something like, ‘What about the sound?’ Like if you can’t hear the bike it’s not actually going fast. I’m going off on a tangent, but it strikes me as a funny opposition.

So then came the day of the big race, The One Pro, inside a 12,000-seat historic venue right in downtown Portland. Part of a weekend of motorcycle celebration called The One Motorcycle Show. I expected the race to be so quiet

that you could hear the grunts of the racers or some shit-talking in the corners, possibly even a pin drop. As it turned out, that wasn’t the case. The buzz of the crowd and the whizz of the chains created a unique and satisfying sound, loud enough to feel the intensity but not the ear-destroying scream of ten bikes inside your grandma’s house. And it was the best racing I saw all night. Every bike was set up to a different spec, but with the same game-levelling power. It came down to aggressive riding and a slow hand. Sammy Halbert came out victorious, but not by his usual half-a-lap lead. It was anyone’s win, and all the riders could see the glory of winning the first ever Electric National. You’d better believe we will be doing this again next year, bigger and better (but not louder).

TD @the1moto

(above) Halbert’s One Pro Race spoils; (below) Sammy’s celebratory burn out at the end of the first Electric National

Always wear a helmet, protective eyewear and clothing and insist your passenger does the same. Ride within the limits of the law and your own abilities. Read and understand your owner’s manual. Never ride under the influence of drugs or alcohol. Copyright © 2020 Indian Motorcycle International, LLC. All rights reserved. BOOK YOUR TEST RIDE INDIANMOTORCYCLE.CO.UK/FIND-A-DEALER @indianmotorcycleuk @indianmotorcycleuk

SCRAMBLER STYLING

WITH MODERN PERFORMANCE.

Who? What? When? Why? Where?

Anthony Brown

Interview: Gary Inman Illustrations: Toria Jaymes/ Stay Outside

You head up the Dirt Track Riders Association, running flat track races in the UK and Europe, and you’re the current European vintage flat track champion, but when was your first bike race?

It was at a speedway training track, that doesn’t exist now, inside a banger track1, in Farringdon, Oxfordshire, UK. I was 14, so it was 1987. I was riding a methanol-burning, 500cc, two-valve Jawa speedway bike.

My dad, Dickie, was a speedway enthusiast who used do vintage demonstrations [read about Dickie in SB24]. It was a pirate race meeting, there were no age limits, so I was against anyone else on a 500cc speedway bike. Previously, I had a moped that I used to ride around a field, but this was my first bike and I did terrible. I’d ridden that track a couple of times, slowly got the hang of it and when the race meeting came up I entered. I was nervous. Racing that bike was like trying to ride a rocketpowered cricket bat. It was so fast.

Did you ever turn pro?

I was never pushed, it was just, ‘See how you get on’. I rode speedway from the age of 14 to 19. I rode for the Milton Keynes Knights, I signed for them on my 16th birthday. At that point I was racing once, sometimes twice a week. I raced for a season and a half. I won my first ever speedway race in my last meeting for them. During that season I put someone through the fence and broke their

Appendix

back and knocked myself out. That made me think I probably didn’t want to do this long term.

I stopped speedway and did two seasons of grasstrack, representing the South Midlands Centre team, which was a big deal. Simon Wigg2 was our captain. Grasstrack was a big deal then and it was hard to get into that team. Then I went to university and didn’t ride much when I was there, I used to go mountain bike racing, downhills and avalanche cups and that sort of stuff. At the same time, I was passengering a guy in pre-’65 sidecar motocross. I didn’t have any money and he paid for everything. When I got a job I bought a trail bike and started doing some enduros. That was the first time I’d ever ridden a bike with brakes. Before that it was speedway and grasstrack only.

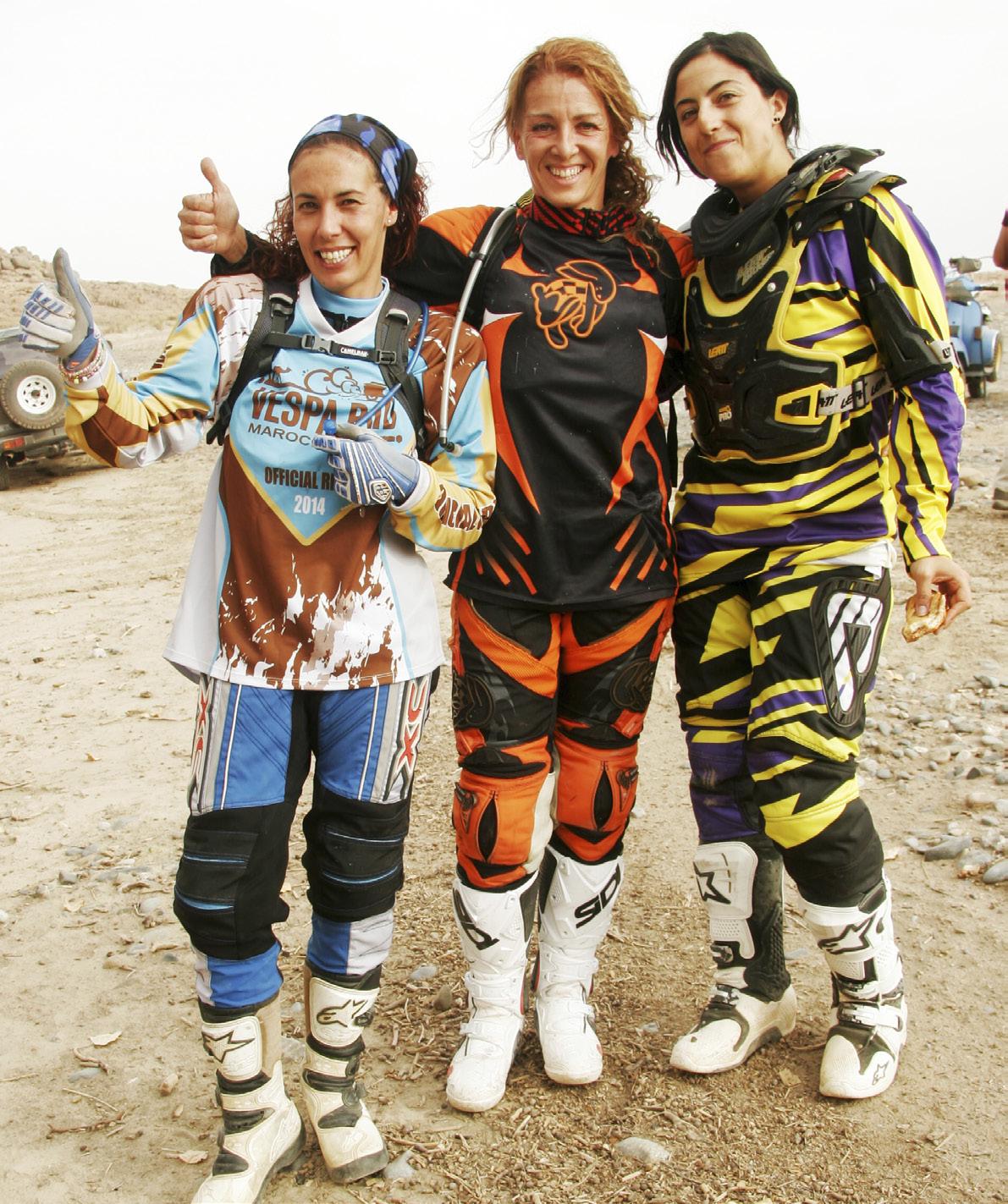

I used to do long-course enduros, where a lap would take the whole day. That progressed into doing rallies; the first was in 2004 and I did about four of those in Morocco. I worked for the organisers at two Tuareg Rallies.

How did flat track come into your life?

It was the year Kenny Roberts’ MotoGP team finished in the UK3 , as a celebration of winding up they organised a day at Peter Boast’s CCM Flat Track School. I think it was end of 2007. Me and Geoff Cain4 went along. We rode the DRZ-powered CCM FT35 at Rye House and that was it. I bought an SR500 and went flat track

racing. My first race was at Buxton. I had a shitty start in my first heat, everyone fell off in front of me and I ramp-jumped a bike that was lying on the ground. I finished out that season and over the winter we built the first Co-Built Rotax5

What has been your most memorable win so far?

The most memorable result, not a win, was 14th at Weston Beach Race [in Weston-super-Mare, UK] on a sidecar against 120 motocross sidecars. Everyone in front of us was a pro motocross sidecar team. I was driving and Geoff Cain was passengering. If it’s a win, it would be the 2011 Short Track UK Thunderbike series. I’d never won a championship before.

What’s your favourite flat track?

Mariánské Lázně. It’s in the Czech Republic. It’s in the centre of town, surrounded by hotels and houses. The town looks like it’s out of the film Grand Budapest Hotel, a spa town, they have to sweep the streets after a race because it’s a deep, pea gravel track, nearly 1100m (almost three quarters of a mile) long.

What the best bike you’ve ever raced?

My Co-Built Rotax. The best bit about it is I’m racing it in the knowledge that me and my friends built it. The Rotax engine is a simple, tuneable motor that lends itself really well to a flat track bike with good handling.

1. Banger racing involves stripped-out former road cars (old bangers). Colliding with opponents’ cars to damage them is the norm. 2. Grasstrack and speedway pro, five-time world long track champion. Died of a brain tumour in 2000, aged 40. 3. KR’s MotoGP team was based in Oxfordshire, UK, Anthony’s home county. He was friends with some of the employees. 4. Co-founder of Co-Built, racer, frame maker, exhaust fabricator. 5. Anthony, Geoff and motorsports design engineer Barry Ward have created a number of Rotax-powered

framers under the name Co-Built. See SB9.

>

And the worst?

I raced a rigid Triumph grasstrack bike called Killer. You had to put your leg under a bar on the right-hand side and full-leg trail with your left. Nearly everyone who got on it ended up severely hurt. I rode it at Reading speedway track and didn’t get hurt, but it was super sketchy. Because your leg was trailing, you couldn’t do anything to save a crash and the front wanted to tuck all the time.

What’s the worst injury you’ve suffered?

Either multiple concussions or a broken leg, depending how I get on in 20 or 30 years and if I can remember anything or not. Or perhaps when I impacted speedway track shale up my bumhole. I was racing speedway and I’d almost worn through my leathers doing practice laydowns then we had a practice race at the end of the day and I crashed going into the corner, my leathers wore through and the dirt went right up inside. I had to sit on a pile7 cushion at college for two weeks. Or the time I crashed and my cock went black.

Who is the toughest competitor you’ve raced?

Wayne Drake in the Thunderbike class. If he wasn’t beating me, he was falling off in front of me or running me over.

Who is the greatest flat tracker of all time?

Because greatness is not necessarily about someone who’s done all the winning, I’m going to say Aldana. I feel his reputation, personality and charisma – and the fact he still races after all this time – is inspirational.

You run the series in the UK and Europe. What made you want to take that on?

First and foremost, I didn’t want it to stop, because I was enjoying it. Secondly, I’ve always been involved in helping organise motorsport in some way or other and there’s

Appendix

a lack of people prepared to do that.

I felt if I didn’t [at that time] nobody else would8 .

What’s the best bit about running the DTRA?

When you see people who’ve had a really great day, then the feeling on a Sunday night when you’re finished and you don’t have to think about it for a few days.

organisation, does that help you make decisions?

It takes the pressure off making business decisions, because you can make them based on values. If the main purpose of the DTRA is everyone comes along and has a good time, you can make the decision based on that, not on how much money it’s going to cost, as long as the club can afford it.

6. Deliberate lowside crashes. 7. Piles is UK slang for haemorrhoids. series, Short Track UK, ceased promoting races.

NEW KRIEGA MAX28 EXPANDABLE URBAN BACKPACK #RIDEKRIEGA

Tyres and Wheels

THE TYRE THAT pro riders have been using in the Grand National Championship since Ben Franklin discovered electricity is the Dunlop DT3.

When I started racing, it was branded a Goodyear, but it was the same pattern.

But the American Flat Track (AFT) series spec tyre for 2020 is completely different in terms of shape, tread pattern, construction and thickness. The DT4 is the first new tyre to be used in pro flat track in the last 40-plus years. I tested it a couple of times in off season and it’s an improvement over the DT3. It’s thicker and has a more aggressive tread pattern.

So far, I’ve only used it on cushion short tracks, so I’m looking forward to trying it on a groove track.

IN THE COMPOUND

For years, on certain tracks, Dunlop has offered a choice of what tyre compound we can use. The tyre looks the same, but the compound is softer or harder. When I turned professional, back in 2007, we didn’t have the option. Everyone used the softer compound on short track and TT events and the harder option on half-miles and miles. This choice makes it harder to decide the best compound for each track. Last year, Production Twins riders like me only ran 15-lap main events, so the majority of us used the softer compound on half-miles. At the Rapid City Half-Mile it seemed the softer compound overheated for most riders in the semi, so most of us switched to the harder compound for the main. However, it got colder when the sun went down and the track surface cooled. Ryan Varnes, the only rider with a softer compound rear, kicked everyone’s ass. In fact, he had the fastest lap time in the whole event, including the more powerful premier Twins class.

CUTTING AND DOPING

When I was a rookie professional, we were allowed to do a lot of tyre prep. We could cut extra grooves into the tyres, enhance them with chemicals (doping) and also use a tractionizer – a big-ass roller with spikes sticking out. You let the air out of your tyre, put the bike on the roller and

give it throttle. This puts little holes in the rubber, which helps on dusty, clay tracks.

AFT doesn’t allow tyre prep, but your race series might, so here’s what to consider and why. We would cut tyres with special tools, or sometimes razor blades. This was mostly for cushion tracks with a loose surface, because the fresh razor edge allowed it to bite into the dirt. At non-AFT cushion half-mile events, it’s almost essential to cut your tyre as it usually improves lap times by 0.5s. At Lima, I went through a brand new tyre every time I hit the track because it’s essential to have those sharp edges.

It doesn’t make a huge difference on clay tracks, though. Taking rubber away is usually a bad thing on hard-packed surfaces, so we search our truck for scuffed-in rubber or half-worn tyres.

I’m glad we don’t have the option to put chemicals on our tyres or use a tractionizer any more. Doping is a pain.

The price of chemicals and finding the best way to do it seems like hell. I don’t know what some of the tuners like Kenny Tolbert and Bill Werner used back in the day, but I’ve tried doping my tyres at some outlaw races and not noticed a huge difference; perhaps I wasn’t doing it the right way. It’s brutal talking to grown men who race go-karts, but those guys are experts when it comes to prepping tyres.

FEEL THE WIDTH

After you decide what tyre compound you want to use that day, you then have to decide what width wheel is best. The popular options are 2.5in or 2.75in front wheels and 3.0in or 3.5in rears. Most often, a narrower front is used on the cushion tracks to open up the tyre tread a little more and allow it to slice through the dirt; same with the rear wheel. However, a lot more guys have switched over to the 3.5in rear in the last few years. I use a wide wheel almost everywhere when riding the G&G Racing Yamaha MT-07 twin. The wider rim seems to help me keep the wheels in line and hook up off the corners better. Brandon Robinson almost never uses a wide wheel, even at Springfield Mile. It’s rider preference when it comes to width.

MIXING IT UP

At non-national events, we can pretty much do whatever we want with our tyres, including choosing a brand we feel works best for that surface. In addition to Dunlop, the main options are Mitas, Maxxis, Shinko, and soon, Hoosier. The Mitas are badass on dirt/clay cushion tracks and seem to work good almost everywhere. Maxxis have been around a while and are more limestone or gravel tyres and can be unpredictable on clay tracks. One lap, it’s badass and hooked up, and then five laps later it’s complete shit. If you stick to the Maxxis on cushion tracks only, you’ll be dialled in. I have never used a Shinko, but I haven’t heard great things about them. I haven’t yet tried the Hoosier, it’s still in development.

WEIGHT A MINUTE

We have a 42lb-complete rear wheel with tyre weight rule in AFT. Last year it was 40lb, but the new DT4 is a heavier tyre so they gave us leeway. Some riders only use heavy wheels and some riders never use them. I feel like the heavier wheel allows me to carry more corner speed and sort of keeps the momentum going through the apex. On tight, paper-clip-shaped tracks, having a heavier wheel makes it harder to slow the bike down, so that is something we look at when deciding what is best.

PRESSURE ON

Tyre pressure is important, but I never notice a major difference changing the pressure one or two pounds. You can go so in depth with pressures depending on the track length, dirt, tyre brand, etc. Pressures will be different depending on the type of bike and size of engine. Even, say, a framer 450 and a DTX 450 often require different pressures. The common range is eight to 30psi. I’ve seen riders run as low as eight pounds at a track like the old Daytona short track because it’s so smooth and slick. On the mile tracks, especially Springfield, you run a high pressure because of the speeds and how hot the tyres get.

It’s not as simple as putting rubber on a rim and going racing, eh?

23

They’re the interface between you and the track. AFT champion Cory ‘C-Tex’ Texter shares his hard-earned knowledge to help you make a difference

Illustration: Prankur Rana

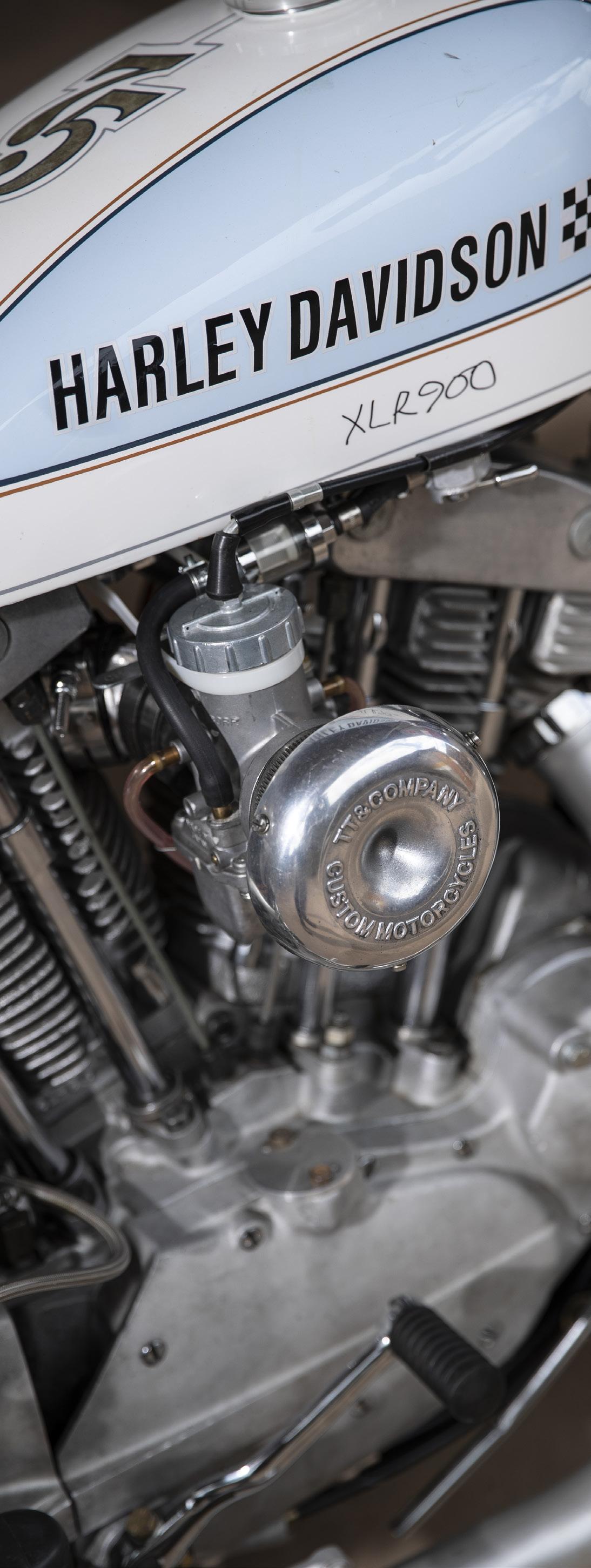

Words: Bill Jackson, Gary Inman

Photos: Caylee Hankins, Harley-Davidson Museum (archive)

This image is credited as the reason why Harleys are nicknamed Hogs. It a firm favourite of Sideburn, so much so we paid homage to it...

> 25

Recreation in Skidbrooke, Lincolnshire, UK, 17 February 2020

>

1920

Born in 1890, Ray Weishaar began racing in 1908, aged 17, at half-mile county fair tracks near his home of Wichita, Kansas. His success earned him the nickname ‘The Kansas Cyclone’. By 1916, he was on the US national circuit and joined the relatively new Harley-Davidson racing team.

His most celebrated victory came in 1920 at the 200-mile national at Marion, Indiana, a race also referred to as the Cornfield Classic. Over the course of the weekend, Weishaar adopted a piglet from a local farmer as the H-D mascot and named it Johnnie. Following the victory, a photo taken of Weishaar offering a soft drink to the pig became one of the most iconic photos in Harley-Davidson history.

Ray Weishaar raced for another four years until his life was cut short by an accident during a race at Ascot Speedway in California in 1924. BJ

2020A century later, George ‘Greenfield’ Pickering pulls on a reproduction Harley-Davidson jumper and climbs into a small, straw-lined pen to bond with a shivering piglet. We’re in windy, cold North Lincolnshire to replicate the famous images of Ray Weishaar and Johnnie. Why? Because I wanted to.

We’ve rounded up family and friends; bought some hats from a charity shop; had regular contributor and self-taught leather worker Jason hand-make a one-off piglet harness that looks just like Johnnie’s, oh, and borrowed a pair of just-weaned piglets from a local farm. Two, to keep each other company and so if one gets stressed in front of the camera we can swap them. Our piglet is pink, Johnnie was darker. George’s sweater is pristine, while Ray’s was filthy from a 200mile race, following, at least for some of it I assume, pioneer race bikes spitting oil from their straightthrough pipes and gasoline from crude carbs.

Who knows what Ray Weishaar or the original, unknown photographer would make of our homage, but I really hope it would make them as happy as it makes me. GI >

Thanks to: Katie Barker for the location and piglet handling; our models: George Pickering, Margaret Pickering, Rosemaree Waite, Wendy Barker, Rachel Robinson, Debbie Inman and Eve Inman; Steve Buckley for the loan of the piglets; Nik at HarleyDavidson and the H-D Museum in Milwaukee. Go visit them, you won’t regret it.

SAFETY, FUNCTION & STYLE 15 TIMES STRONGER THAN STEEL Premium Motorcycle Clothing Brand

Snow Tiger

Hookie’s impulse buy proves you should trust your gut

Words: Maximilian Funk Photos: David Ohl/Hookie Co 33

NICO DID WHAT every one of us has done at least once – dived into a passion-driven quick buy. The story begins back in November 2018, with a link to a purple

Triumph on eBay shared on the Sideburn website.

Sideburn didn’t vouch for the bike, just put it out there as something interesting. Nico, of Dresden-based moto design company Hookie, got on the case and four weeks later the bike arrived at the shop in Germany.

It looked good, but wasn’t running. Nico immediately started to strip the bike down. What he found was not what he’d hoped for. It was in bad condition. Really bad. The overhaul began as spontaneously as the deal itself. During the Hookie Christmas dinner a couple of drunk guys took the engine apart, which resulted in one of the best evenings ever at the shop.

The engine was handed over to Carsten from South Division in Munich, a man with over 40 years’ experience. He was given a short and efficient brief: ‘I need a flat track engine for European tracks’. Two months later, Nico drove down to Munich and did the final assembly with the engine guru. As a bonus, he got an intense, four-hour blast of knowledge on this particular motor. Upgrades include: primary lubrication running with the main oil system, highcompression pistons and polished intake ports. The brake pedal and gear shifter are now both sitting on the right of the engine. Electronic ignition is fired by dual coils powered only by a battery (4Ah = 60 minutes of fun). Wassell carbs have replaced the Amals and breathe through bigger K&N pod filters via 3D-printed adapters. Whoever invented the 3D printer – thank you!

>

(clockwise from top left) Hookie Co mix old and new tech. Bates seat came with the bike but the tank is wrapped, not painted; Reworked BSA forks; Triumph ’bars; TT Bonnie-style pipes; Nico at Krowdrace on the bike in a previous guise; Honda CB/ Brembo match-up

Since the frame was an unknown quantity and not a Trackmaster gem, Nico started modifying. The bottom section was replaced, with new engine mounts and extra bracing, plus the steering head rake was steepened. An aluminium oil tank sneaked in, and an aluminium rear fender too. The existing Bates seat and p-pad worked just fine with the vintage look. The fuel tank aluminium with a fibreglass cover by Mike Hill of UK-based Survivor Customs, since the original was leaking. Up front are shortened and overhauled BSA forks, while wheels are 19in BMW snowflakes running on Duro HF308 tyres. The rear brake is made up of a Honda CB rotor with Brembo caliper paired with a BMW master cylinder.

Originally, the bike ran in the brakeless class in the US from the ’70s till the late ’90s, always with the number 53. Unfortunately, no more background information is available. It took Nico four months to rebuild the complete bike and the first proper race outing was Krowdrace in Diedenbergen, Germany.

After some small carb tweaks, it performed really well. Oh, apart from a flat rear tyre. The original tube from 1977 blew, which was totally unexpected…

>

1967 Triumph T100R Snow Tiger

Engine 1967 T100R.

Primary lubrication runs with main oil system; high compression; polished intake ports; dual-coil electronic ignition running on 4aH battery

Frame Unknown with new bottom rails with extra bracing by Hookie Co; New engine mounts

Carbs Wassell with K&N pods on 3D-printed adapters

Forks BSA (overhauled and shortened)

Wheels 19in BMW snowflake with Duro HF308 tyres

Rear brake Honda CB rotor, Brembo caliper, BMW master cylinder

Oil and fuel tanks

Aluminium with fibreglass fuel tank cover by Survivor Customs

Other Aluminum rear fender; Triumph handlbar; Venhill throttle with cable splitter; Renthal Ultra Tacky grips

©2020 H-D or its affiliates. HARLEY-DAVIDSON, HARLEY, H-D, and the Bar and Shield Logo are among the trademarks of H-D U.S.A., LLC. CELEBRATING 50 YEARS

Scout Sixty

The Hooligan with Pigtails is one of the few people worldwide to have raced, and won, on Indian Motorcycle’s Scout Sixty and their S&S-prepped FTR 1200. But which is the best big vee?

Words: Leah Tokelove Photos: Kayadaek Photography

CLASH

vs

TWO YEARS IN and I’m in pretty deep. I seem to have been engulfed by all things hooligan.

At the start of 2018, a few months prior to my hooligan debut, I’d never even sat on a V-twin motorcycle, let alone raced one. But I’ve been completely consumed by a whole new culture I knew nothing about – and I love it. My racing world now pretty much orbits the hooligan scene. I’ve proved, if you dedicate a lot of time to something and strive for better, change and progress can happen.

43 >

FTR 1200 CLASH

When you can get the tyres to squeal you can’t help but feel like a hero

For me and Indian that change occurred midway through the 2019 season, when we jumped from the solid Indian Scout Sixty, customised by Krazy Horse (which had taken me to fourth in the 2018 championship), to the all-new, bitchin’ and pimpin’ road-based FTR 1200, rebuilt solely for racing flat track by S&S Cycle. The FTR 1200 [see SB37] was inspired by the popularity of Indian’s multi-championship-winning FTR 750 [SB27] and when performance kings S&S got their hands on a 1200, they really did build the mother of all hooligans. At the time of writing, there were only three S&S FTR 1200s in existence (two in Europe, one in the US) and my booty gets to grace one of them. I’ve flipped it, stacked it, dropped it and raced it hard.

We’ve had a funny ol’ ride together so far. This flat tracker built for the street could well be the ideal donor bike to develop into an unstoppable hooligan-slaying machine, and on its maiden voyage in a UK DTRA race, it really was.

The S&S FTR 1200 pushed me to do something that I had thus far failed to do. I beat Gary Birtwistle, reigning DTRA Hooligan champion, for the. First. Time. Ever. As a result, I got my first UK Hooligan final win and set the day’s fastest lap! I didn’t have the best start, starts are something I struggle with on this bike, much more than I did on the Scout Sixty. The 1200 is tall for my 5ft 3in and I can just get down the tippy toe of my left boot while still being able to cover the rear brake with my right. My ugly starts always leave me behind both Gary and fellow Indian racer Lee Kirkpatrick going into the first corner. After playing catch-up for the best part of five laps of an eight-lap final, I found myself teetering into Gary’s personal space. I was right on his back tyre, and out of nowhere I had this inner drive to push myself and the bike harder than ever before. So, I just went right on in there, I forced my front wheel up the inside of him, trying to put the pressure on and edge him out. And it worked! Exiting the corner, I unleashed the 1200’s

>

(above) Checking out the competition on El Rollo’s startline. Californian Rob Bush (whose back also features in this issue’s Perris story) is on the Krazy Horse Scout Leah was racing prior to the FTR’s arrival. Next to her is a 2019 Brough Superior. Yes, really; (left) Death stare at Krowdrace, Germany

potential and got so much drive down the straight. Everything just felt right. For the remaining few laps I was on an emotional rollercoaster; everything from ‘Don’t arse this up’ to ‘OMG yaaas Queen, you’ve got this’, all to the soundtrack of Ludacris’s Move Bitch Get Out The Way. And the most beautiful part? I got to re-watch it all on TV, because I did it at DirtQuake.

Where did this newfound confidence on the bike come from? Well, I’d been practising a whole lot on it for starters. And, unlike a lot of hooligan bikes, the S&S FTR 1200 actually looks like it should be raced. S&S Cycle head up Indian’s AFT race team, they know their stuff and have some incredibly talented people. One of the biggest issues with the hooligan Scout was its weight, clocking in at nearly 250kg (550lb) it felt a bit like backing in a cruise ship. The FTR 1200 comes in at 190kg (420lb), which is 25kg (44lb) lighter than the road version thanks to removing, y’know, stuff, so it begs to be ridden more aggressively.

The 1200’s crowning glory is that stainless-steel S&S exhaust. I think it’s the pipe we all dreamt of for the road version. The racing Scout also came with a beastly roar in the form of a Krazy Horse two-into-one exhaust that sat low on the bike. One thing’s for sure, neither bike lacks chat.

The FTR has an adjustable Fox monoshock with remote reservoir and OEM cartridge forks, which work well. The Scout came with an Öhlins front suspension cartridge upgrade and Öhlins twin shocks. Compared to the FTR, the Scout felt so much more planted, arguably down to the nature of the bike – after all, the Scout is a cruiser. I could put both feet flat on the floor and, importantly, I never crashed the Scout, whereas the FTR bucked me off in the first hour. Mind you, the FTR is much narrower than the Scout, so I no longer feel like I’m riding a rhino. I think what also made the Scout feel so planted was its long wheelbase, it was a proper unit and it took a lot to upset it. The 1200 I race has an S&S swingarm, 25mm shorter than stock, and this, added to the taller stance, makes the bike feel slightly more twitchy – but it does look right. I’ve had countless remarks about it. People love the FTR. I haven’t heard anything negative about the way it looks.

I’ve raced to victory on both bikes. In 2018 at Wheels & Waves, I took my first overall win riding the Scout on El Rollo’s dusty short track. Both victories on the FTR have been on much longer tracks and the 1200’s power is a really important element. When you twist the throttle it’s so responsive, but not a handful, and it sure makes it easier when you’re wheel-to-wheel exiting the corner and just wanna get away. Interestingly though, the FTR’s power delivery has been toned down compared to the road-going version, with a new ECU and maps, the idea was to make it a tad tamer for the track and therefore less likely to spin up.

I’ve really enjoyed riding both bikes on grooves, particularly at Greenfield in the UK. With bikes so big and heavy, it’s nice to ride a consistent track where you

can really push harder. Plus, when you can get the tyres to squeal you can’t help but feel like a hero. With regard to tracks, it’s worth noting that the FTR arrived chain driven and with multiple sprockets, allowing us to make important changes at different ovals. Although the Scout Sixty did eventually get the conversion from belt drive, we only ever had one sprocket.

Alongside racing in the Hooligan class, I usually ride my 450 in the DTRA’s Pro class too, and I managed to make all of the Pro finals last year, placing eighth overall in the DTRA Pro championship. It’s a weird feeling jumping between a sweet DTX bike and a gnarly hooligan, made even more alien when you want to ride them both hard in consecutive mains. Getting onto my 450 and hooning it into a corner, I feel unstoppable, the bike just glides beneath me, a featherweight. Jump back on big Bertha and you get a sharp reality check. If I’m honest, I’d rather not have to race them on the same day.

After just half a season I think I’m getting there with the 1200. It’s a real privilege to race one and I’m so impressed by the team at S&S Cycle, not only for the effort that has gone into developing a hooligan bike to such a high standard, but also with the support they give me. Long term, I want to show everyone what the FTR and I are capable of. Like any racer, I think that winning feeling is the sweetest.

Sure, at the end of the day the FTR is just another highly inappropriate motorcycle thrashing around a relatively small dirt oval and causing ears to bleed. But isn’t that what hooligan racing is all about?

How good it feels to win on an Indian 35 17 5 27 28 30 15 23 27 30 13 87 40 30 10 1023 Euphoric 87% Euphoric (but in red) 13%

Made in the USA • sscycle.com • @sscycle • #sscycle Race-ready parts for your Hooligan build Heatshield Kit for Hooligan 2:2 Exhaust Stealth Air Cleaner Kit w/ Mini-Teardrop Cover Bolt on Hooligan Kit1200cc to 1250cc & 482 Cams Stainless steel Hooligan 2:2 Exhaust System

All thrills. no frills. Vintage style meets modern technology. Packed with features you need and nothing you don’t. Meets DOT & ECE Regulations / XS-XXL Sizes / Ten Colors WWW.BILTWELLINC.COM @BILTWELL

Metallic Candy Red (New for 2019)

Metallic Candy Red (New for 2019)

Geoff NicklesSGeoff NicklesS

Kenny Roberts at Laguna Seca, 1979. The Ferrari 308 GTS was a gift from Yamaha for winning the 500cc World title

51 >

The Californian photographer talks about 45 years of shooting motorsport just for the love of it

Interview: Mick Phillips Photos & captions: Geoff Nickless

S SOON AS we spotted the photography of Geoff Nickless on Instagram, we loved it. Here was this rich seam of petrolhead porn in saturated ’70s colours and crisp black and white, with grand prix bikes and cars; early AMA Superbikes; motocross; close-up, dirt-in-the-teeth flat track action... Then there were the candid pit shots on the shoulder of great riders and drivers. Not just classic stuff, but modern as well. Oh, and lots of Kenny Roberts – riding, chatting, holding court... But something was missing. Well, a couple of decades seemed to be missing. We decided we needed to talk to Geoff Nickless.

‘I had to put my passion for photography on hold while I worked in the architectural field. After retiring in 2016, I realised that I missed going to the races. I finally had the time and means to begin attending again.’

So let’s get back to the beginning. Born and raised in Sacramento Valley, California, Geoff first got interested in photography after graduating from high school in 1972. He took all the classes available at Sacramento City College, from a beginners’ course in shooting black and white to advanced colour photography and printing.

‘I got my first SLR camera in 1974, a Minolta SR-T 101 with a 50 f/1.7. Next was a Vivitar 75-260 f/4.5, because I wanted to photograph racing in Northern California (Sacramento Mile, Sears Point in Sonoma County, and Laguna Seca in Monterey). I then progressed to a Canon F1 and a couple of years later I bought another F1 so I could load one with Ilford FP4 ASA 125 black and white film and the other with Kodak Kodachrome 64 transparency film.’

(above) Roberts in the pits at the 1974 Golden Gate Fields Mile, Albany, California. He won the main; (below left) Freddie Spencer on the Honda NS500 checking on his competition, in Turn 9 at Laguna Seca, 1982

Geoff first made his mark in 1975. He’d set himself up at Laguna Seca’s Turn 8 for a round of the AMA Grand National Championship, back when road racing was still an integral part of the series.

‘I captured a really good shot of Kenny Roberts, when he was the AMA Grand National Champion. I photographed an 8x10 print that I had made, with Kodak high contrast copy film. I then printed that negative on 16x20 Agfa print paper, with a contrast rating of 6, their highest contrast paper, and mounted it on matt board. I finally got the nerve to offer it to Kenny in 1977 at Sears Point Raceway. He really liked it and said, “Wow! That is really neat, I haven’t seen anything like that.” He asked, “How much do you want for it?” I told him he was my favourite rider and if he would take it that would make my day.

He then said, “I see you get press passes.” I told him I wished I did, but that the shot was taken standing on an oil drum to get up over the fence. He then said, “Come and see me next time, I’ll get you a press pass.”

‘The next time I saw Kenny was in 1978 at Laguna Seca, he remembered me and gave me a press pass. At Sears Point in

(above) Eddie Wirth in Turn 1 on his XR750 at the 1975 Sacramento Mile, during time trials. He went on to be a very accomplished sprint car driver, winning the California Racing Association Championship in 1985; (right) Brandon Robinson gets into Turn 3 a little hot during practice at the 2019 Sac Mile. No, he didn’t save it. He slid under the air fence and laid motionless for nearly a minute. Thankfully, he was uninjured and raced in the main

>

1978, I gave him four 11x14 black and white prints mounted on matt board, to show my appreciation. He gave me another press pass. I never thought that would happen! This continued until 1985 when he retired.’

Geoff was strictly amateur, so his day job couldn’t be allowed to suffer, and what with Kenny’s absence from the paddock, plus increased pressure at work, he stepped back from photography until 2005.

‘My wife, Barb, and I went to the 2005 MotoGP at Laguna Seca. I shot film with my F1 and 80-200 and it was very difficult to get any good shots, so I started putting together new kit. Last year, a friend we met through Kenny Roberts at his annual charity dinner, Andy Johnson, Senior Director of Business Development for Cycle Gear, who is a fan of my work, offered us photo passes. Barb and I now go and photograph as many races as we can for Cycle Gear. She’s learning to shoot with the extra camera. Andy doesn’t put any restrictions on our work and we’re not paid, so that still makes me an amateur photographer!’

All that time away from the tracks has given Geoff a clear perspective on the way racing has changed over the years.

‘The rules now are much stricter than they used to be. Kenny would just pull a press pass out of his pocket and give it to me. Now, you have to work for a magazine, a website, an official company or have your photos published before you can get a photographer’s pass. I would have my pass pinned to my camera bag, now I have to sign a waiver, wear an official photographer’s vest and attend a safety meeting. It’s very restrictive and sometimes you just aren’t allowed to get to that location to get the shot you have in mind.

‘Years ago, I could go pretty much where I wanted and just use some common safety sense. I have photos from the 1975 Sacramento Mile where the track entrance for time trials was on the outside of turn one, with hay bales as the only protection for the officials and riders on their bikes waiting to go out. There were even riders watching, sitting on those hay bales with their legs unprotected, getting roosted when someone would ride the cushion.’

And, of course, the kit has changed significantly since the 1970s and ’80s (see separate box over the page).

The distancing of fans and photographers, especially in grand prix racing, has been one of the more negative changes over the years, but 40 years ago things were pretty different.

(above) Roberts being introduced before the 25-lap main at the 1977 San Jose Mile. He designed and built Kenny Roberts Racing Frames chassis for his Yamaha OW72 dirt tracker. The bored-out Yamaha XS650 engine was built by Shell Thuet Racing Specialties

‘I was walking past Kenny’s 1979 YZR500 (OW45) grand prix bike and actually got a couple shots with the heads removed after it was inspected for after-race tech, right down into the cylinders – piston crowns and cylinder walls. That would not happen today. I have not printed them and nobody has ever seen them. Now it’s almost impossible to get a good photograph of the MotoGP bikes when they are not on track. Someday, I really would like to get a photo of that snaking upper titanium exhaust of a Honda RC213V.’ One thing that hasn’t changed much is that you can rely on the flat track community to be far more accessible, even at the highest levels of the sport.

‘The dirt trackers are whole different story. In 2017, I asked if I would be allowed to take

“The next time I saw Kenny was in 1978 at Laguna Seca, he remembered me and gave me a press pass”

“The next time I saw Kenny was in 1978 at Laguna Seca, he remembered me and gave me a press pass”

(above) Yamaha factory team-mates Gene Romero (3) and Kenny Roberts get ‘under the paint’ exiting Turn 4 during morning practice at the 1974 Golden Gate Fields Mile. (below) Kyle Wyman in Laguna Seca’s Turn 8, the top of the Corkscrew, on his Ducati Panigale V4R in 2019

(above) Yamaha factory team-mates Gene Romero (3) and Kenny Roberts get ‘under the paint’ exiting Turn 4 during morning practice at the 1974 Golden Gate Fields Mile. (below) Kyle Wyman in Laguna Seca’s Turn 8, the top of the Corkscrew, on his Ducati Panigale V4R in 2019

>

Wayne Rainey exiting Laguna Seca’s Corkscrew in 1983 on his Kawasaki GPz750 superbike. I gave Wayne a print of this last year. He said, ‘1983, that was one of my favourite championships.’

GEOFF’S KIT

My equipment is so much better today than it was years ago. I had good equipment, but my longest lens was a Canon FD 80-200 f/4. Now I shoot with a Canon 5D MkIII and a Canon FE 100-400 f/4.5-5.6 L, a Canon FE 400 f/4 DO and Canon tele-converters (1.4x and 2x) for track shots. My paddock lens is a Canon 24-70 f/2.8 L. Barb shoots with a Canon 7D MkII, Canon 70200 f/2.8 L and a Canon 16-35 f/2.8 L when in the paddock. GN

some photos of the new Indian FTR750. One of the Indian team said, “Sure, come on around the barriers and shoot whatever you want.” Then he started pointing out items that I may be interested in. There was so much carbonfibre and titanium, I was amazed.

‘I remember my instructors from school telling me that everybody sees things at eye level, five to six feet above the ground. If it will work with your subject, try to shoot higher or lower than at what most people see things. This will make people take a longer look at your photograph, because there is something different about it.

‘Always try to fill your frame with the subject. It doesn’t always matter if the front or the back of your subject is cut off, it can have a very dramatic effect. And passion for your subject matter and patience are things you need.’

And passion this is. Geoff is definitely not in it for the money.

‘I have always been an amateur. I have never sold a photograph, just given them away to friends, riders... and recently to Kenny Roberts’ annual charity auction for returning veterans.’

@nicklessphotos

SYD · BALI · LA · MLN · TKO · BIQ · IBZ · AMS · CPT DEUSCUSTOMS.COM

アイスブルーレーサー IceBlueRacer Words:InuchopperKei Photos:KentaroYamada

61 >

(clockwise from above left) Things got so skinny the fuel pump became shrinkwrapped in alloy; Early sketches explore options; You want swooping bodywork? If you’re Cheetah you form it by hand from aluminium sheet; Temporary overflow bottle shows the bike runs; Shakin’s ice blue paint gives the bike its name; Ducktail’s exhaust – more pie cuts than an apple pie contest in Pie Town, New Mexico; Made by hammer, welder and hand. Dings and dents need not apply

IF YOU’VE BEEN following Sideburn for the last year or so, you’ll be aware of the Have Fun Flat Track gang from Japan. A group of friends, many of them talented fabricators and mechanics, who made a name for themselves first by building their own 150cc flat track framers to race for kicks at Japan’s only short track oval, then by organising practice days and races to kickstart the sport in Japan after a recent lull. They were approached to build a custom version of the current Fantic Caballero to promote the Japanese launch of the bike. One of the crew, Kei, shares the details...

Many of the Have Fun friends took on a different task and the Ice Blue Racer combines Cheetah CC’s free design and Ducktail Watanabe’s solid work. Cheetah formed the bodywork and fuel tank by hand from aluminium sheet. The tank and integrated seat and radiator shrouds give the bike’s silhouette a traditional flat tracker style. Then the bike was sent to Ducktail

>

Have Fun Custom

パブファンカスタム

Watanabe, who was in charge of producing the front number plate and pipe.

The exhaust and silencer are stunning examples of Watanabe’s art. The exhaust pipe is created from stainless-steel straight pipe that has been expertly piecut in more than 30 sections to get a smooth curve. It’s a masterpiece. The muffler is also one-off, with a certain volume and a flat track racer feeling, with good sound and performance. While the Italian street tracker was at Ducktail’s he also lowered the front and rear suspension.

Next, Skunk Kubota took charge of the shape and cover of the wild, extended seat and Shakin’, the painter, laid on the ice blue metallic – that gives the bike its name – the lettered inserts and graphics. The paint was designed to make the one-off aluminium skin stand out in a crowd.

The bike was built in a hurry, even though Cheetah and Watanabe live 350km (220 miles) from each other. Shakin’ made two round trips between Ibaraki and Miyagi. Watanabe also made two round trips between Tokyo and Miyagi. This bike travelled 2400km (1500 miles) in vans before it put a tyre on the dirt.

The friends got it finished just in time for Mooneyes’ world famous Hot Rod Custom Show in Yokohama, then, as all the best bikes do, it hit the track two days later, at the Have Fun Flat Track Party.

The result is a custom flat track racer that brings out the Caballero’s true character.

TwinBLUE COLLAR

Shawn Baer’s budget-build Production

Words: Gary Inman Photos: Ed Subias

BMW

LIMA HALF-MILE 2019, on the cusp of change in AFT’s SuperTwins era. The Grand National Championship has never been short of polish or professionalism, the bikes that compete in the US national series are the cream of flat track, but 2020 will see the sport make a further step up in the way it presents itself to the outside world. Pro motorsport can’t operate without major sponsors, that’s what enables it to be pro, and AFT’s latest round of changes is designed to attract more money to enable top riders to receive financial rewards that reflect the risks they take. While every rider with pro pretensions dreams of earning a wage, it isn’t a reality for many, and not everyone fits in with AFT’s new direction. One such rider is 33-year-old Shawn Baer. Shawn has ridden a number of different marques: Triumph, for the Bonneville Performance team, then his own Kawasaki Ninja 650 framer, on which he scored top tens in the 2012 season as a privateer. ‘Then we raced the Mega Mile1 and I don’t know why, but we lost three engines in one day and we never got it back.’

Along with his father, Daryl, of Baer Racing Products (BRP), Shawn had the idea of building a KTM 990 2 to replace his Kawasaki.

>

67 Appendix 1 Colonial Downs, Virginia, a 1.25-mile cushion oval. 2 We featured Shawn’s KTM 990 in SB20.

‘Using a KTM meant we were starting with an engine that had 100 horsepower, not a Kawasaki with 54-60, where we were looking for an extra 40bhp to be competitive. I never had the financial backing, I work as a machinist during the week. The KTM allowed me to continue racing.’

If the KTM sounds like the ideal solution, a reliable 100bhp from stock, there is a downside. ‘Jeffrey Carver raced a Suzuki 1000 for Weirbach Racing and he said to me, “I don’t know how you [race those big twins]. I want something that handles.” The big KTM is harder to get around,’ admits Shawn.

Baer has the physical build to hustle the heavy Austrian and revel in its privateerfriendly punch of tuneable cheap power. It’s likely he would have still been racing it now if the rules hadn’t changed to lower the engine capacity limit, essentially outlawing the KTM. Shawn still wanted to race at the highest level and liked what the KTM had offered, so began looking for an engine that was smaller, but similar. He landed on BMW’s F-series parallel twins, at that time already being developed for flat track by the legendary Ron Wood.

‘The BMW is producing 85-90bhp and I hope we can make 100 reliable horsepower. It’s a parallel twin with a 360-degree crank, the pistons rise and fall together. There are, I think, four different models and the GT is the one you want. I buy the engines off eBay for between $500 and $900.’

(above) Bare metal and development parts will be transformed before the BMW’s next outing. Blingy Vortex sprocket stands out (opposite) Straight off the track, peppered with Ohio gravel

Shawn goes on to explain that all he changes is the cam, made for him by Web Cams; the ignition, which is a Performance Electronics PE3 system from Ohio, is the same unit Howerton Racing were using on the Bryan Smith Kawasaki; Rottweiler velocity stacks on standard BMW throttle bodies, and a Rekluse clutch, that he raves about. But, he admits, ‘When Ron Wood passed I lost my in with a man who’d won a race 3 with the BMW.’

Shawn is now ploughing his own furrow –experimenting with cams, building motors without balancer shafts and, sometimes, ‘grenading’ engines. ‘I built a new engine and it let go on the fourth or fifth lap. When I took the head off, one piston was completely missing. The conrod was still there, but there was no sign of the piston. It was in the sump.’

Shawn isn’t overly pleased that we couldn’t wait to feature the bike, because he tries to build the nicest motorcycles he can, and when we shot this Baer BMW, at its very first outing, it wasn’t a reflection of the slick bikes he normally builds. However, he did agree that it is an important document of the development and, while it’s a bit rough around the edges, it couldn’t look any tougher.

Shawn and his dad designed the chromoly chassis and it was welded together by John Klahr, a friend who builds roll cages for dirt track sprint cars, using Shawn’s own jig. The swingarm is made using 1in tubing, bigger than most chassis builders use, because Shawn likes the rigid feel it offers. The shock is a Penske; forks are Yamaha R6 in the family’s own BRP adjustable triple clamps, used by, among others, former Super Hooligan national champ, Andy DiBrino.

Shawn’s generous uncle Ron paid for the alloy tank to be made by Mike Taylor, a fabricator based in Shawn’s home state of Pennsylvania. It houses a Kawasaki 650 fuel pump. ‘They never fail,’ says Shawn.

In this early-development guise, the quick and dirty exhaust pipes are of Shawn’s own making – mild steel bends, bought online, and $40 end cans.

‘People have told me the bike would make more power if I had ‘down’ pipes,’ he says, referring to low, under-engine exhausts, ‘but I’m a guy stuck on the image of flat trackers and I think they should have ‘up’ pipes. Down pipes aren’t flat track.’

As noted, Shawn is a machinist by trade and those radical wheels are his own work. ‘I bought the blanks from California and machined them myself. I’ve been making my

Appendix 3 The Wood Racing BMW 800 won the AMA GNC2 Arizona Mile in May 2016 with Dalton Gauthier on board. It was the first (and, so far, last) time a BMW won a pro flat track race. GNC2 is now called Production Twins.

>

own wheels since 2010. People say you want power, but what you really want is traction. I started making heavy back wheels after Joe Kopp was caught filling his inner tube with water and the AMA changed the rules to stop that. Then he had a steel wheel made that weighed 60-70lbs, but that was banned too, so I started machining these heavy rear wheels [that are within AFT’s weight limits]. I wasn’t copying anyone and I’m proud that now everyone is using heavy rear wheels.

When we spoke, in early 2020, Shawn didn’t seem sure where he and his bikes fitted into

Baer machines his own wheels from blanks, working up a heavy rear in the ever-crucial hunt for traction

the new-era flat track scene. He’s competed in Expert Twins for years, but can’t commit to SuperTwins and the new requirement of committing to enter every race, or try for one of the limited wild-card spots, but Production Twins and the big non-nationals are options.

Shawn is symbolic of the dirty-hands racer many fans feel is the core of flat track. As the very top of the sport goes through its transformation, riders like him will either mutate to survive or move to the non-national circuit to battle for the prize purses. Baermotorsports.com

PERRIS

73 >

Words

&

photos: Scott Toepfer

SoCal’s favourite short track

CALIFORNIA IS A great many things to its residents, but to racers of all types it is a place of history and speed. As deep as that history is, dirt ovals keep disappearing, and Southern California only has a couple of places left for the public to go fast and turn left. Car tracks remind motorcyclists that ‘You are lucky to have a race at all’. It is very true, we are lucky to have anyone willing to pony up the cash to host an event or series for a ragtag bunch of loonies trying to outrun ‘progress’.

One track still holding out for the motorcycle contingent is Perris Raceway. Not to be confused with the larger, half-mile Perris Speedway at the other side of town, which allows a single professional AFT race each year. Little Perris has a long history of bringing the pros and the amateurs together for quick laps and a feeling of community. It’s currently the only track with a proper motorcycle race series schedule in Southern California.

I first attended a Perris event in 2013, or maybe 2014. I’d run out of fun in the hooligan/outlaw classes at Ventura on my street-legal 441, and bought my first Triumph [as featured in SB38]. I went to Perris for practice, and ran laps until my body could take no more punishment. I made mistakes, took advice, made more speed, slid around, slid too far around, kissed the plywood wall, and found a love for the place. Nowhere I had ridden before had allowed me to run as many laps as I could handle, on a track immaculately prepped and open to allcomers.

Professionals would also come to practise, and to race for outlaw purses whenever the schedule allowed. Nicky Hayden would come and ride and say hello to everyone in the pits. NICKY FREAKIN’ HAYDEN! Surely he would have somewhere ‘more important’ to be. But no. The track is a magnet for fun. The top riders of our sport

(clockwise from top left) Cody Kopp, son of former US #1 Joe and a future champ in the making, getting some framer seat time; Bush Bros’ barrio hooligan; How many rider meetings has this place seen; 2019 X Games Best Whip gold medalist Tyler Bereman getting his turn left kicks; Don Galloway did a 3400-mile round trip from Edmonton, Cananda to race his Panther; The night before the AFT race across town and Brandon Robinson is tearing it up; Bereman on the fence; The heart and soul of SoCal short track; Mom and Dad are still the biggest sponsors in the sport

>

(this page) The Savage Customs CRF450 framer Stace Richmond races. The Savage crew travelled from Washington state (opposite) Pit bike, iPhone, GoPro, smile

(clockwise from top left) Do you take trade-ins?; Racers, including Go and Masumi of Brat Style, check grid positions; Rotax framers make us smile. #10 is a Knight; Scott Jones and his XG750 hooligan

would show up and duke it out with the locals, risking their careers and livelihoods to swap paint with roofers and carpenters as the sun went down and the lights turned on. These were magical moments. Those summer afternoons gave us sweat-and-dust-caked faces, tons of laughs and let us pretend there were no limitations.

Over the years, I would visit when I could. Sometimes to race, but more often to spectate. As one of the few holdout racetracks, I knew I needed to give it my support as well as revel in the vibe. I would wander the pits, saying hello to friends eagerly cutting tyres or getting geared up for their turn on the track, indulge in the track food and always be tempted to swig from the cleverly hidden front-seat bottle of Fireball.

Despite being one of the few havens of our sport here, the track itself has come under a lot of scrutiny. Neighbours’ complaints have led to restriction of exhaust decibels, which in turn has left some racers out. But in all honesty, Perris is the place still holding out for motorcyclists. I recently heard Chris Carr mention that being a young flat tracker in California is more difficult than in his amateur years, when he could race two or three times a week. Ventura has shut down motorcycle racing save for a single memorial race, and Willow Springs hinges upon Eddie Mulder’s willingness to hold racing for a single weekend of the year. So many people think of Southern California when they think of flat track, but it can feel pretty grim for the current community at times. I am sure the almighty dollar has squeezed tracks all around the country in the same way, but it makes these nights at Perris all the more important to cherish.

BoltxEdie

London moto apparel and custom builders team up with bikes-in-the-blood clothing designer for a ciderfuelled collaboration. Destination: Paris fashion week

Words: Andrew Almond Photos: William Waterworth, Cole Quirke, Tom Pigeon, Andrew Almond, Edie Ashley

81 >

IFIRST CAME across fashion designer Edie Ashley as an enigmatic and fearless force at various motorcycle events; she tends to stand out in a crowd. From winning best effort on her vintage Cheney Triumph on the Swank Rally at Wheels and Waves, to taking off into the Welsh hills near her home town, she’s had motorcycling ingrained since a child. When I received an invite to her graduate show at East London’s Truman Breweries, I was excited to see how her background in motorcycling had transfered to the catwalk. The collection drew on influences from motorcycle garments dating back to the 1930s and reworked them to a contemporary, tailored style. It was great and, as the owner of Bolt Motorcycles – a shop in London – my kind of thing. So, immediately after the show we headed for a drink and decided to collaborate on producing a collection together.

This was an opportunity to focus more or less entirely on the form and to create garments that reflected motorcycling for its pure style. We began with an

academic process of working through our large collections of literature; classics like Rin Tanaka’s guide to leather jackets and helmets are some of the best. With over a hundred years of inspiration to plough through we focused on small details, those borne from functionality and that defined the garments as motorcycle attire. The asymmetrical-buttoned jackets from ’30s TT races, the different style of knee and elbow padding and the high waist of vintage scrambling trousers were all inspirations.

Explaining our collection to Mark Wilsmore, owner of London’s Ace Café, he made the interesting observation that motorcycle attire was becoming increasingly more conformist while, in contrast, fashion trends were adopting the traditional symbols of rock ’n’ roll. The contemporary custom scene has attracted new audiences and grown alongside a revival in heritage

styles, adopting a more gentlemanly appearance than previous motorcycle subcultures. Long gone is the image of the leather-clad menace and the attitudes bestowed on the original greasers. There has been a preoccupation in motorcycle clothing with marrying style on and off the bike. It’s creating a need to fit in, to appear like everyone else, a monoculture of mass trends adopted at a surface level. Meanwhile, current high street trends extend from studded leather jackets to direct references to outlaw motorcycle gangs; the look is much more counter-cultural. With BoltxEdie we wanted to create something innovative and authentic that championed one’s identity as a motorcyclist.

From the outset, we decided to use only reclaimed fabrics, there is more than enough already. This we

(clockwise from top left) Race Wrap top in vintage Crêpe de Chine; Edie in the Race Wrap top and vintage trousers; Cosy! Models (the designers’ friends) in a mixture of BoltxEdie and classic motorcycle clobber; Lightbox shining brightly outside the gallery in Paris; Like moths powered by free booze, crowds form outside the fledgling brand’s Paris launch; Edie and sister Lily playing records at the party; Forget the rag trade, we’ve invented wheelbarrow pool, we’re going to be millionaires!; Edie, Rosie and Lily on Edie’s Cheney Triumph

soon realised would take us on a series of adventures, countless wild goose chases and the occasional pot of gold. Our most intriguing lead had to be the news of cases of silks dating back over a hundred years that had been found intact in the hold of a sunken ship off the coast of Devon. However, they had yet to be retrieved and it was going to take more than a snorkel and flippers to get them out of there.

It was a regular at Bolt who told us about an old workwear factory in the north of England that he had taken possession of. It had been in decline for decades and in that time had built up a mountain of apparel filling all five floors of two warehouses. Always a fool for curiosity, it wasn’t long before I had organised a truck and a trip up north to see what we could find.

We came off the motorway and drove over the moors before dropping down into Dewsbury. Rows of terraced

>

houses, in the pale sandstone you see all over Yorkshire, formed geometric patterns on the hillsides. The warehouses were boarded up and in a state of disrepair. We were quickly ushered in and the doors locked behind us; apparently the previous owner was not well liked and a number of firebomb attacks had followed his departure.

There were three of us, five floors and innumerable shelves of bails of clothes tightly packed from floor to ceiling. If this wasn’t enough, there was a huge, unlit cellar and an attic, both packed to their capacities with more bails. By my own conclusion, the best stuff had to be the hardest to reach, and with this in mind, guided by the faint glow of our phones, we clambered down among the sea of bails and started trawling for our catch.

After eight hours of fishing through the stock we pulled together our findings. Edie had netted rolls of satin-faced moleskin while I’d found boxes of new-oldstock zips from the 1930s onwards. There were Talon, Aero, Cliq, Lightning and other military zippers; I was proper geeking out on the find. But still we needed more. Finding enough fabric to produce the collection took us to Paris and eventually to a small fabric house that traded off-cuts from the famous Parisian ateliers. We were now starting to build up a handful of reliable dealers who would put aside any unusual fabrics for us and over the months we had filled a garage.

The next stage was to create the twills, essentially these are the dry builds for the garments to come. This took place in the Bolt garage with a team of fitting models, pattern cutters and seamstresses working away among partly dissembled motorcycles and benches covered with tools. We stood around with cups of coffee, refining every seam, adjusting and re-adjusting the fit, trying to find that perfect equilibrium of form and function.

It was Edie who suggested we launch at Paris Fashion

Clothes and motorcycles look best when set in movement...

as the hotel lobby. Outside, we came across the bright orange electric scooters that litter the streets of Paris and suddenly they seemed a lot more appealing. Literally the antithesis of everything I like about two-wheeled travel, I justified it to myself as an electric walking stick and that since even looking at my feet hurt it might actually be my only feasible means of mobility. Edie was bang up for it and before long we were tailing the traffic up the Champs Elysees at a mild pace of 19kph (12mph). Taking on the Arc de Triomphe with its six lanes of traffic and no road markings was more challenging.

We’d seen 50 venues in two days when we stopped, exhausted, and agreed that the first one we’d seen was clearly the best. In the heart of the Marais, tucked in a corner overlooking a quiet, cobbled street, the venue was perfect. When we arrived back at London’s King’s Cross station I would have happily dragged myself on my belly along the platform to avoid using my feet.

We were now down to just three weeks and our to-do list was a mile long. Our plan was to present the collection alongside an installation, photography and film exhibition. Both Edie and I have a good circle of creative friends so we invited as many as could come down to Edie’s family farmhouse in Wales. Over the course of a few days and with motorcycles, horses and gallons of homebrew cider, we planned to shoot the collection. Our only problem was that as car after car arrived we were still without the samples. Eventually, after a lot of phone calls, we were promised that a stranger would arrive on the last train with samples in hand. We had to cross our fingers and enjoy the cider.

Week rather than in London. It was ballsy. This gave us a month to prepare but I had no idea where to start. I figured the first step would be to find a venue. We jumped on a train and started to search the Paris streets for a suitable space for our launch. We covered 32km (20 miles) on foot that first day and it was painfully clear that the only pair of shoes I’d taken had a good chance of bringing me to my knees.

The next day, I shuffled along at such a pace I didn’t think we’d make it as far

Thankfully, the midnight exchange went smoothly and the next day we rose with the sun and started shooting. Edie directed the shoot, with William Waterworth photographing portrait, Cole Quirke a more documentary style on film and Joel Kerr capturing everything on Super 8. Clothes and motorcycles both look best when set in movement, and, with a vintage Cheney Triumph scrambler and a more modern Beta, we headed into the hills above the farm, found some jumps and spent the next few days fooling around. As we descended on the local pub, en masse, we were welcomed by the locals, an incredible bunch, and I spent the night listening to the old timers telling stories of wins and escapades representing Wales in enduro racing.

Almost everything for the Paris show was being made bespoke, from the metal display cases to the vinyl window splash commissioned from artist Joel Clark. On top of this, we had 100 scarves to print and sew by hand, sound systems, drink sponsors, press releases and invitations to organise; we didn’t sleep in the final week. It ended up that everything being made was to be delivered the day before we set off.

Miraculously, it was.

The next morning, we loaded our mate Rui’s van with a 1943 flathead Harley,

We found some jumps and spent days fooling around

Materials are a mix of satin-face cotton, Crêpe de Chine, moleskin and duck canvas. Start the diet now

>

1972 Guzzi Eldorado, the Cheney Triumph and my own Triumph café racer, and headed to Paris. With so much to do, I’d left finding accommodation till the night before, that’s the night before the start of Paris fashion week. Hotels would have cost thousands, as would an Airbnb – if there was anything left. There was a tiny boat just big enough to fit a mattress and I resented paying to be a stowaway. My other option was an incredible-looking chateau which looked too good to be true. Then I realised it wasn’t even in Paris. That was a short while after I had booked it.