SPRING/2023 DESTINATION PEMBERTON GOING FOR GOLD PROSPECTING 101 BCMAG.CA

DITCH THE LAWN, GROW VEGGIES GO NORTH MUSKWA-KECHIKA ON HORSEBACK & THE NORTHERN WONDERS OF HIGHWAY 37

URBAN GARDENING

Tā

Provincial Park

Boya Lake,

Ch'ilā

The historic River Ranch 3,933 acres, 39 titles, 17 km frontage on Nechako River, 2 houses, office, accommodation buildings, conference hall, 44 room unfinished hotel, off-grid with solar and generators, airstrip. Barn, corrals, 1,200± acres of hay and grassland, Range Permit rights. Wildlife. $4,995,000

RICHARD OSBORNE

Personal Real Estate Corporation

604-328-0848 rich@landquest.com

Located just minutes from town center the nicely treed lots are located just as Stuart Lake becomes Stuart River. Build three residences or just keep a couple lots for an investment. Hydro, gas and Internet is available all along paved Sweder Road. Country Life at its finest. $295,000

KURT NIELSEN 250-898-7200 kurt @landquest.com

FORESTED ACREAGE WITH MULTIPLE DWELLINGS & SUBDIVISION POTENTIAL - SCOTCH CREEK, BC

Beautiful acreage (162 acres) in the North Shuswap with loads of potential. Zoning allows for 10 acre lots. Significant timber value. Extensive improvements including multiple homes and cabins, large shops (plural!). Off-grid services with BC Hydro nearby for connection if desired. $1,550,000

MATT CAMERON 250-200-1199 matt @landquest.com

THE HAVEN - A TRANSFORMATIONAL LEARNING CENTRE - GABRIOLA ISLAND

6.77 acres with 426± ft of low bank walk-on oceanfront. The 16 buildings accommodate up to 120 guests. Long established not-for-profit centre for transformational learning can be enriched and expanded or transformed into a resort, private residence, or your vision. NOW $5,200,000

JASON ZROBACK 1-604-414-5577 jason @landquest.com

JAMIE ZROBACK 1-604-483-1605 jamie @landquest.com

Quiet and private view acreage at the south end of Galiano with two off-grid cabins and spectacular ocean and mountain views. Seasonal creek, large mature timber, and several meadows. Drilled well and driveway in place. Priced to Sell at $595,000

DAVE SIMONE 250-539-8733 DS @landquest.com

FAMILY HOME AND HOBBY

Stunning views from this very well maintained 24.76 acre hobby farm in the Bella Coola Valley. The picturesque property is perfect for a small hobby farm. It is complete with numerous outbuildings, raised garden beds, fruit trees, established berry bushes, electric fencing, river access and more! $595,000

FAWN GUNDERSON

Personal Real Estate Corporation 250-982-2314 fawn @landquest.com

THE RANCHES AT ELK PARK CLIFFSIDE RANCH - RADIUM HOT SPRINGS, BC

Picturesque acreage (230 acres) at the foot of the Rocky Mountains in the Prestigious Elk Park Ranch. The most quintessential Columbia Valley views imaginable. Micro hydro system serving a greenhouse structure with a residential suite. Fully forested with established trails throughout. $1,899,000

MATT CAMERON 250-200-1199 matt @landquest.com

FISHIN’ HUNTIN’ AND LOVIN’ EVERY DAY NECHAKO LODGE - KNEWSTUBB LAKE, BC

The Nechako Lodge has six guest rooms, a commercial kitchen and large gathering area. There is also a two bedroom residence, four cabins and six RV sites. Solar and wind power the property. Includes a foreshore lease with docks, breakwater and boat launch. $795,000

JOHN ARMSTRONG

Personal Real Estate Corporation 250-307-2100 john @landquest.com

Pristine south-facing waterfront home on Lake Cowichan with 90+ ft of gentle sloping beach frontage. 2,100 sf home with large windows throughout offering views from every room of the house. 10 x 20 ft landing, 54 ft aluminum ramp leading to a new 10 x 24 ft private dock. Sit around the fire pit on the pebbled beach and enjoy the peaceful tranquility of the lake. $2,250,000

KEVIN KITTMER 250-951-8631 kevin@landquest.com

7,117 ACRE CONTIGUOUS FARM OPERATION IN THE HEART OF BC’S PEACE RIVER REGION - FORT ST. JOHN, BC

Contiguous 7,117.57 acre farm in the Altona area of BC’s Peace River region. This immaculate farm offers 9 km of river frontage on the Beaton River. Possesses rich soil and fertile growing conditions. The current farm tenants grow a variety of crops including fescue, canola, barley, peas and oats. Production information is available upon request. Approximately 4,613 acres are in cleared production with the production land situated in a cohesive block. The farm derives $11,700 per annum in oil / gas revenues. These facilities are unobtrusive in nature. There are 16 separate titles and approximately 10 grain bins. Various creeks and dugouts are located throughout the farm. The remainder of the property is timbered, but there could be additional lands cleared and put into production. $6,500,000

FAWN GUNDERSON

Personal Real Estate Corporation 250-982-2314 fawn @landquest.com

NAKISKA RANCH WELLS GRAY PARK - CLEARWATER, BC

472 acre guest ranch that generates great income. Main house / lodge to live in, along with many outbuildings for ranch operation. Cabins & lodge accommodation are booked solid from May to October. 300 acres of timber & 170 acres in hay, generating about 600 round bales. Can support about 50 cow - calf pairs. 29 km from Clearwater in Wells Gray Park. $2,999,000

ROB GREENE 604-830-2020 rob @landquest.com

LAKEFRONT EQUESTRIAN ESTATE LAC LA HACHE, BC

This estate ranch is a 29.78-acre world class lakefront equestrian estate. Accommodations are 3 custom log homes, 2 custom log cabins and 8 serviced RV sites situated on 1,400 ft of unobstructed lakeshore on beautiful Lac La Hache. $4,100,000

JOHN ARMSTRONG

Personal Real Estate Corporation

250-307-2100 john @landquest.com

® Marketing British Columbia to the World® www.landquest.com Toll Free 1-866-558-LAND (5263) Phone 604-664-7630 Visit Us Stunning views from this very well maintained 24.76 acre hobby farm in the Bella Coola Valley. The picturesque property is perfect for a small hobby farm. It is complete with numerous outbuildings, raised garden beds, fruit trees, established berry bushes, electric fencing, river access and more! $595,000 LARGE, NEWLY RENOVATED FAMILY HOME WITH SHOP - HAGENSBORG / BELLA COOLA, BC Sam Hodson Personal Real Estate Corporation 604-809-2616 sam @landaquest.com 317 acres 20 minutes from Prince George. 85 acres hay land. 2 km riverfrontage on scenic Chilako River. Includes main house with 4 bedrooms, 1 bath and second home with 3 bedrooms and 1 bath. 32 x 22 ft shop with cement floors and 200 amp power. Storage sheds, workshop, hay shed and 2 loafing sheds. Some timber. $1,179,000 AFFORDABLE STARTER RANCH CLOSE TO TOWN PRINCE GEORGE, BC CHASE WESTERSUND - WESTERN LAND GROUP Personal Real Estate Corporation 778-927-6634 chase @landquest.com COLE WESTERSUND - WESTERN LAND GROUP Personal Real Estate Corporation 604-360-0793 cole @landquest.com

FARM BELLA COOLA, BC

5.4 ACRES IN 3 TITLES LEVEL FORT ST. JAMES RIVERFRONT

LAKE COWICHAN WATERFRONT YOUBOU, BC

10 ACRE OCEAN VIEW WILDERNESS PROPERTY GALIANO ISLAND

THE HISTORIC RIVER RANCH VANDERHOOF, BC

BC MAG • 3 Contents 24 BC & the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance Renting a motorbike to explore the province, a nervous writer becomes an easy rider 32 Archie’s Guide to Highway 37 Experiencing the wonders of BC’s North 44 The Muskwa Kechika: Land of Legacy Cowboy dreams fulfilled in this two-week trek through the “Serengeti of the North” 52 Going for Gold

beginner’s guide to a time-honoured BC tradition—gold prospecting 60 Urban Gardening

rising food bills and concerns over scarcity, the time has never been better to explore your green thumb 68 Redefining Small-Town BC

new rec-tech summit reimagines how we live, work and play in resource and tourism-dependent rural communities 4 Editor’s Note 6 Mailbox 8 Due West 16 Destination Pemberton 74 Backyard Getaways Fort Langley 82 BC Confessions Burial at Sea IN EVERY ISSUE Cover Photo Destination BC/Andrew Strain VOLUME 65 - ISSUE 01 SPRING 52 Tā Ch'ilā Provincial Park 16 68 74 32 44 FEATURES

A

With

A

SPRING

Gold Fever

THE LURE OF GOLD is one of British Columbia’s most enduring and romantic notions. Ever since the Gold Rush in the mid 19th century, fortune seekers the world over have travelled here to search our waterways and rock formations for this lustrous metal. What was once a life-changing gamble 150 years ago has turned into a profession occupied by mining companies, private claim owners and social-media prospectors, as well as a hobby for people with a gambler’s heart and a love of the outdoors.

I fall firmly into the latter category. As I’ve talked about in these pages before, I’m always up for a little “hiking with a purpose,” whether that’s fly fishing, rock hounding and, most recently, panning for gold—all at the most amateur of skill levels, of course. Just as Linda Gabris describes in her story “Going for Gold” on page 52, I too caught my gold fever at the gold panning display during a road trip to the historic mining town of Barkerville. After watching my kids find little gold flakes in their pay dirt, I was inspired to purchase one of the Barkerville-branded gold pans they have available in the gift shop—thinking that this was going to be my new hobby.

After several years with that gold pan sitting untouched in my closet, I finally gave it a go during the depths of Covid isolation at a little stream by our family cabin on Vancouver Island. I had read in one of Rick Hudson’s articles on rock hounding that gold was found just upstream from the road crossing near us, and surely the expertise I gained from watching my kids pan for gold one time would lead me to riches on the

riverbank. That wasn’t even remotely the case, but it did provide us with a fun afternoon of scooping up gravel and washing it in the pan in the creek.

Just like my no-catch fly fishing outings, I’m not one to let bad luck stop me from enjoying a hobby. In fact, soon after this expedition I purchased a high-powered magnet to go magnet fishing off the dock (a little more success here, as I pulled a rusty log boom spike from a lake), and eventually purchased a metal-detector “for my son,” which has found us a pile of rusty nails and aluminum cans.

This past summer, BC Magazine art director Arran Yates and I took a backcountry road trip on the Hurley Forest Service Road from Pemberton to Gold Bridge, with half an idea to try all this stuff out. We had a great time crawling around the old, abandoned mining equipment and tailings, and imagining ourselves living in the Bridge River Valley all those years ago. Of course, we had no luck finding anything of note with the gear, but I did get a consolation prize of grabbing some nice pieces of nephrite jade to take home as treasure.

That road trip is simply amazing, and we have plans to do it again this summer with hopes of striking rich. Though this time we’re going prepared with a little more knowledge, both from Linda’s great article in this issue and by watching Aussie Gold Hunters online. But as the saying goes, the chase is better than the catch, so I’m sure we’ll have a blast even if we strike out.

—Dale Miller

EDITOR Dale Miller editor@bcmag.ca

ART DIRECTOR

Arran Yates

ASSISTANT EDITOR Blaine Willick

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Sam Burkhart

GENERAL ADVERTISING INQUIRIES 604-428-0259

ACCOUNT MANAGER Tyrone Stelzenmuller 604-620-0031

ACCOUNT MANAGER (VAN. ISLE) Kathy Moore 250-748-6416

ACCOUNT MANAGER Meena Mann 604-559-9052

ACCOUNT MANAGER Katherine Kjaer 250-592-5331

PUBLISHER / PRESIDENT Mark Yelic MARKETING MANAGER Desiree Miller

GROUP CONTROLLER Anthea Williams

ACCOUNTING Angie Danis, Elizabeth Williams

DIRECTOR - CONSUMER MARKETING Craig Sweetman CIRCULATION & CUSTOMER SERVICE Roxanne Davies, Lauren McCabe, Marissa Miller

SUBSCRIPTION HOTLINE 1-800-663-7611

SUBSCRIBER

cs@bcmag.ca

4 • BC MAG

ENQUIRIES:

SUBSCRIPTION RATES FREE with your subscription: the British Columbia Magazine wall calendar. 13 months of glorious landscape and wildlife photography. 1 year (four issues): $19.95 / 2 years: $34.95 / 3 years: $46.95 Add $6 for Canadian, $10 for U.S., or $12 for International subscriptions per year for P&H. Newsstand single-issue cover price: $8.95 plus tax. Send Name & Address Along With Payment To: British Columbia Magazine, 802-1166 Alberni St. Vancouver, BC, V6E 3Z3 Canada British Columbia Magazine is published four times per year: Spring (March), Summer (June), Fall (September), Winter (December) Contents copyright 2022 by British Columbia Magazine. All rights reserved. Reproduction of any article, photograph or artwork without written permission is strictly forbidden. The publisher can assume no responsibility for unsolicited material.

1709-4623 802-1166 Alberni Street Vancouver, BC, Canada V6E 3Z3 PRINTED IN CANADA Canadian Publications Mail Product Sales Agreement No. 40069119. Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Circulation Dept., 802-1166 Alberni Street, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6E 3Z3. Tel: (604) 428-0259 Fax: (604) 620-0245 WWW.BCMAG.CA

ISSN

EDITOR’S NOTE

ROAD TRIPS WWW.BCMAG.CA/ROADGUIDE 1.800.663.7611 AVAILABLE THIS SPRING ORDER ONLINE HIGHLIGHTS INCLUDE Winery & Cidery Tours / Craft Breweries / BC Pit Stops / Iconic Destinations Hidden Gems / Cross-Border Trips / Detailed Maps & Drive Times / and lots more! VOLUME 5 - COMING SOON

Mailbox

Buy it here

BOWRON LAKES

The article on Bowron Lakes in the Fall 2022 issue could not have been better timed, as last week I gave a talk to my Rotary Club in Wales on our canoe trip around the Bowron Lake chain in early September 1967. Paul Lyons and I rented a timber canoe and drove up from Vancouver. We set off after a brief chat with Davy the park ranger, who mentioned grizzly bears and the fact that he did a weekly circuit around the chain in the event we were stranded! We were there in the first week in September and on day two it snowed (a bit different to the 30 degrees mentioned in the article). When we got to Lanezi Lake, the trapper’s cabin was occupied, so we camped next door and dried our saturated sleeping bags by the wood stove. The two Canadians who were there shared a couple of Kamloops trout (a 12 pounder) steaks with us! The following day we climbed to Hunter Lake for the most amazing fishing experience as suggested by Davy. After day four, we ran low on food so subsisted on trout until we got back to the ranger’s trailer.

no prepared campsites, shelters or smoke! What an experience.

Dick Boyle, Wrexham, Wales, UK

MOUNT SLESSE CRASH

The crash on Mount Slesse was discovered by a team lead by Elfrida Pigou, probably the top woman mountain climber in BC in those days. Later her team was wiped out by an avalanche near Mount Waddington. I think they found an iceaxe. Perhaps that is why she is often forgotten today.

Tom Widdowson, Victoria, BC

WINGS OVER THE ROCKIES NATURE FESTIVAL

I’m a volunteer with the Wings Over the Rockies Nature Festival (Invermere), and I was hoping that BC Mag could

print something about our yearly event

Our festival boasts about a hundred events/activities in the spring, the majority of which have to do with birds. We are located in Invermere, though some of the events take place in other communities of the Columbia Valley. Here in the valley, we live near the Columbia Wetlands which is on the flyway of migrating birds in the spring and fall. Our festival is to celebrate just that—the migration of birds through our spectacular area. Invermere is nestled in the Rocky Mountain Trench (to use a geological term) squeezed between the Rockies and the Columbia Mountains, the Purcell Range to be more exact. Every year we welcome a keynote guest speaker and offer events that range from bird watching with a guide to a concert. We are organizing next year’s event, and I was thinking how wonderful it would be if there was a mention of our festival in the magazine this spring.

Marie-Claude Gosselin, Invermere, BC

6 • BC MAG 6 MAILBOX SPRING

Missed the Winter issue?

COMMENT ON CORMORANTS

I recently picked up your winter edition as I was interested in your article about cormorants. Having been born in the Gulf Islands and been on and around the ocean from Port Hardy to Baja Sur Mexico, I was pretty familiar with these birds.

It was great that the author was able to identify the species and their general population strengths and the various attributes that cormorants have to native populations.

My concern with the article is twofold. The first is the notion that cormorants are an introduced species. Cormorants are not introduced to the Pacific Coast nor the Atlantic Coast nor to any area of the North American continent. The author may have been trying to imply that the use of legislation both federal and provincial created the myth that cormorants were introduced. This is especially true to the Great Lakes where rebounding popu-

lations were used as an excuse to substantiate and order a cull. As invasive species cormorants would not be protected, as they would be if they were a game bird or if they were a species at risk. Implying cormorants were introduced here is not correct, even if the author was trying to show the vilification of the species in other areas, like Ontario. Populations for these birds has fluctuated across North America especially as the result of pesticide use and habitat loss for the last hundred years or more. If someone grows up in an area where there are no cormorants and then through their lifetime see more and more they may think they are invasive, when in fact they are not.

Secondly, having grown up in British Columbia and been on the water around both sports and commercial fishers I have never heard a bad word said about them. For a fisher, their presence may indicate that the fish they were feeding on may

also be what the salmon were eating and a likely place to catch some salmon. A symbiotic relationship if ever there was one. So, they weren’t so much loved as they were tolerated and appreciated.

How can one not marvel at the V shaped passage of dozens in flight just above the surface of the water. A captivating sight. And by the way I grew up calling them shags, just like we called killer whales/orcas, blackfish.

BC MAG • 7 Send email to mailbox@bcmag.ca or write to British Columbia Magazine, 1166 Alberni Street, Suite 802, Vancouver, BC, V6E 3Z3. Letters must include your name and address, and may be edited and condensed for publication. Please indicate “not for publication” if you do not wish to have your letter considered for our Mailbox. EMAIL US

Leonard Fraser, Ladysmith, BC

Due West

DUE WEST

Edgar Bullon/Dreamstime

Once a common sight across BC, these log booms near Squamish are becoming a thing of the past.

The Future of Forestry

Can fast-tracking innovation save old growth and the industry at large?

BY BLAINE WILLICK

IF YOU HAVE been paying attention to recent developments in the forestry sector of BC, you’ll notice a declining trend. Many rural and northern communities that have relied on forestry for decades are now being confronted with lost jobs and mill closures. This is happening in Chetwynd, Houston, Prince George, Port Alberni and many more small communities.

Statistics Canada has reported that in the last 30 years the forestry industry has lost around 40,000 jobs. The issues relating to softwood lumber trades with the US, the pine beetle, the turbulent lumber market and the rise in forest fires have all played a role in this decline.

The BC government has come out with an eight-point plan to protect old growth, stabilize these communities and transition into a more stable and sustainable industry. At the centre of the plan is $25 million for Forest Landscape Planning (FLP)

BC MAG • 9 INDUSTRY

which is a more comprehensive and inclusive approach to forest stewardship than the current industry developed model. FLP collaborates with First Nations and industry to provide greater certainty about the areas where sustainable harvesting can occur.

The province will be doubling the Manufacturing Job Fund (MJF) from $90 million to $180 million. The MJF, announced back in January, will help transition forestry communities in several ways. Mills will be supported to process smaller diameter trees and produce higher value wood products, like mass timber that is a versatile product used in construction, with properties competitive with steel and concrete. The announcement states that the MJF will accelerate shovel-ready projects across the manufacturing ecosystem, with one of the examples being listed as companies that want to expand into plastics-alternative manufacturing facilities.

Another aspect of the plan will accelerate implementation of the Old Growth Strategic Review. The original report from 2020 had 14 recommendations to inform a new approach to old-growth management in British Columbia. Within this plan the government will focus on the acceleration of:

• Developing and implementing alternatives to clear-cutting practices.

• Repealing outdated wording in the Forest and Range Practices Act regulations that prioritizes timber supply over all other forest objectives.

• Increasing Indigenous participation in co-developing changes to forest policy through $2.4 million provided to the First Nations Forestry Council.

• Protecting more old-growth forests and biodiverse areas by leveraging millions of dollars of donations to fund conservation supported by the province and First Nations.

• Enabling local communities and First Nations to finance old-growth protection by selling verified carbon offsets.

• Completing the Old Growth Strategic Action Plan by the end of 2023.

“Our forests are foundational to BC. In collaboration with First Nations and industry, we are accelerating our actions to protect our oldest and rarest forests,” said Premier David Eby. “At the same time, we will support innovation in the forestry sector so our forests can deliver good, family-supporting jobs for generations to come.”

ISLANDS

The Mayne Queen Retires from Serving the Southern Gulf Islands

BY MARIANNE SCOTT

THE RESIDENTS OF THE Southern Gulf Islands— Mayne, Saturna, Galiano, and the Penders—have ridden the dependable Mayne Queen ferry for 57 years. The 287.7-foot (84.96 metre) ferry carries up to 58 cars, plus 400 passengers and crew. Travelling at a top speed of 14.5 knots, the ferry has transported more than one islander generation to Vancouver Island for supplies, groceries and medical appointments. The ferry was constructed in 1965 at the Victoria Machinery Depot and has been a lifeline for the four islands’ populations, as well as transport for the tens of thousands of vacationers, hikers and cyclists who visit during the summer for events like the Saturna Lamb Barbecue.

Saturna-resident Senator Pat Carney (retd) told me her mother wrote an article about the Mayne Queen’s maiden voyage more than half a century ago. “As a multigenerational resident of Saturna,” she said, “I’ve sailed this ferry for decades. It’s my favourite ferry, the queen of the entire fleet. Totally reliable. There’ll never be another like her.”

To celebrate her retirement, the Mayne Queen held two days of events during her last runs among the island quartet. On November 19, she travelled the last service with passengers aboard; many islanders rode the ferry for this last voyage, enjoying the beautiful route, communing with crew who’ve become friends and who’ve been devoted to running and maintaining her. The crew reported that sometimes passengers show their appreciation by bringing donuts.

The next day, the ferry made her last round without passengers. At each island dock, the Mayne Queen was greeted by residents who’d gathered to say farewell.

Saturna’s Priscilla Ewbank told me 150 people came to Lyall Harbour to honour the ship and crew. “The Mayne Queen has a heart of her own to inspire such enthusiastic appreciation and faithful following,” she said. “She’s sailed into the rhythm of the individual and collective heart of our communities.” One Saturna choir member had written a farewell song. An eight-foot banner celebrated 57 years of splendid service. Gifts for the crew were delivered and food was so plentiful, it had to be served on the car deck.

10 • BC MAG DUE WEST

Jevtic

Children, dogs, even a baby in a stroller participated in the farewell ceremony.

The Mayne Queen will not be mothballed but will serve as relief vessel when other ferries are out of commission or need drydock upgrades or repairs. According to BC Ferries, the 107-metre Salish Class ferry, the Salish Heron, replaces the Mayne Queen This larger vessel is the fourth such ferry built in Gdansk, Poland. The Salish Heron can transport 138 vehicles and 600 passengers and crew at a maximum speed of 15.5 knots. She will have to prove herself to garner the affection the Mayne Queen earned over the past five-and-a half decades.

BC MAG • 11

FERRIES

BC Ferries:

“You Barked, We Listened” Pet Pilot

BY JANE MUNDY

BC FERRIES LAUNCHED a three-month trial last September allowing dogs and cats on upper outside decks of the Malaspina Sky on the Sunshine Coast (Earls Cove) to Powell River (Saltery Bay) route. The “You Barked, We Listened” pet pilot launched due to repeated requests from pet owners, and it’s been a long time coming. In a press release, the corporation said, “plans to expand to other routes will depend on ‘pawsitive’ customer feedback.” BC Ferries “loves all animals” according to its September press release, so how could there be negative feedback?

Paul Kamon, Tourism Recovery Specialist with Sunshine Coast Tourism, thinks the pet pilot on this route is a great idea. “There are lots of dogs on the coast and the Langdale ferry has as much traffic as other island routes, so this is a good test market before the Vancouver-Victoria run,” he said, optimistically. “BC Ferries has dealt with a lot of negative press recently so making the experience easier for people with pets is a good step

forward. It is slowly changing from a bare bones boat to more like a cruise experience.”

Robert Head is thrilled that Finn, his 11-year-old duck tolling retriever, doesn’t have to stay in the car during the fivehour trip that includes two ferry rides and a 90-minute drive from the Earls Cove terminal to Powell River. “I’m a bit nervous if Finn has to pee or poop because there isn’t a grassy area. A strip of Astro Turf would have been a welcome addition instead of just providing bags that I already have.

We travelled mid-October and it was cold outside, but we did a few laps on the top deck, just like we did with our kids to get the energy out,” said Head.

“The other passengers seemed happy to see Finn. I hope the option to sit outside continues,

especially in warmer weather.”

Granted, a few bucks have been spent on the project, but perhaps a few blades of Astro turf wasn’t in the budget. Paw prints on the deck mark access points and “water bowls and waste bags will be provided and the area will be routinely cleaned.” Dogs must be leashed at all times and cats must be contained in a travel carrier while on the outer decks. Even in a torrential downpour, most pet parents agree that it would be a huge improvement over the dungeon. On every other route, all animals, with the exception of guide, service or emotional support dogs, must remain in your vehicle or in a designated Pet Area, which many dog parents (including this reporter) refer to as “‘doggie dungeon”

and “the cell”.

On its website, BC Ferries says, “To help you and your pet feel comfortable and at home, Pet Areas on board are equipped with…” believe me, no equipment could make the pet area comfy. There is definitely no room to bring your pet’s favourite blanket or toy. And it too is stressful: During a 90-minute trip from Vancouver (Tsawwassen) to Vancouver Island (Swartz Bay), your pooch could be sidling up to several canines, some of which may not be in the best of moods.

Back in October 2017, BC Ferries’ announced its new rules. Passengers were not allowed to access their vehicles on enclosed decks during the voyage. They can request a spot on the upper car deck, but there are no guarantees if

12 • BC MAG DUE WEST

they will be accommodated. Like many dog parents we opt to stay in the vehicle, unless directed to the dreaded lower (enclosed) deck. You could either go to the designated pet area or leave your stressed-out fur baby alone to chew your seatbelts and shred upholstery.

“The rooms in there seem to be just metal benches,” said Omid Manoucheri, travelling with his dog Sierra. “It’s almost like a jail cell... It’s not super gross, but I don’t know how often they clean it. I’m sure they hose it down once in a while.”

BC Ferries explained that it can’t allow dogs to pass through the passenger cabin because of the food services aboard the boats. A spokesperson said it comes down to a Health Canada regulation. But neighbouring Washington State Ferries spokesperson Ian Sterling said, “We are happy to see our four-footed friends on our ferry boats here in Washington State, however they’re not allowed in the passenger cabin, unless they’re a service dog.” Fair enough.

We asked a BC Ferries spokesperson if and when pets will be allowed outside on other routes anytime soon.

“If the pilot is successful on this route, we will plan to expand the program to other ferries on other routes. It will take some time to assess all ferries and prepare designated areas to ensure it’s safe to allow for cats and dogs. We will keep customers up-to-date about this travel enhancement.” Asked why the Malaspina Sky was chosen, spokesperson Astrid Cheng said the layout “was ideal for the trial as the ship has two outdoor areas and close access to waters for the designated pet areas.” (“Waters” means access to water hoses nearby for both water bowls and cleaning.)

“Overall, the pilot was positive. We are reviewing the feedback and we will provide customers with more information when it becomes available,” said Cheng.

BC MAG • 13

SUBSCRIBE & SAVE TRAWLERS Find your Diamond in the Rough www.pacificyachting.com Tsehum Harbour Cruise Aboard Coastal Supply Ship SAFETY & SURVIVAL WEST COAST POWER & SAIL AIS VS. RADAR PACIFIC YACHTING JANUARY 2020 THE FALL PROJECT SOOKE HARBOUR HISTORIC & FRESH ANCHOR LIKE A PRO WEST COAST POWER & SAIL MARINE ELECTRONICS SPECIAL Spend Less, Catch More PUGET SOUND GUNKHOLES JOHNSTONE STRAIT PORT NEVILLE MCNEILL CHINOOK REGS EXPLAINED ANCHORAGES LIFE IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC SEEKING SOLITUDE WEST COAST POWER & SAIL ECO ISSUE SPECIES AT RISK Monday Anchorage 8 TIPS SAFE DURING COVID-19 2021 CAMPBELL RIVER A HAVEN FOR BOATERS WEST COAST POWER & SAIL SINCE 1968 GUNKHOLE CLAM, HERRING & SIBELL BAYS FALL DECOMMISSIONING CHECKLIST UNLOCKING THE BALLARD LOCKS NORDHAVN 41 12 ISSUES FOR JUST ORDER ONLINE WWW.PACIFICYACHTING.COM OR CALL 1-800-663-7611 $48 ONE YEAR SUBSCRIPTION DIGITAL PLATFORMS ALSO AVAILABLE

BOATERS ARE LIKELY

to view many more whales in 2023 after a record number of sightings this past year in the Salish Sea. In 2022, Bigg’s orcas, who travel between Mexico and Alaska, were seen by whale watching companies on 278 days, while humpbacks were sighted on 274 days between Campbell River and Puget Sound. Alert Bay-based Bay Cetology, a non-profit that studies cetacean populations, reported that the Bigg’s orca count had increased to 370, with 10 new calves born in 2022.

Bigg’s orcas were formerly known as transient orcas, or transient killer whales; their new name honours Dr. Michael Bigg, the Vancouver Island pioneering marine biologist whose research started the study of the different orca species.

Bigg’s orcas feed on seals, sea lions, other marine mammals and squid and there seem to be enough of these animals for the orcas to hunt and eat.

Record Whales Visits in the Salish Sea in 2022

BY MARIANNE SCOTT

BY MARIANNE SCOTT

Humpbacks also continued their comeback after being nearly hunted to extinction for their valuable oil. The 1986 ban on commercial whaling has allowed for the humpbacks’ resurgence. Researchers with the Canadian Pacific Humpback Collaboration just announced in a news release that “396 individual humpback whales were photographed in the Salish Sea over the course of the 2022 season, the highest number documented in a single year for at least the past century. It appears that the food supply is plentiful helping to sustain these massive mammals.” The Collaboration also reported that of the whales

photographed last year, most of them have returned repeatedly to the Salish Sea, thus showing they have clear preferences for where they choose to feed.

The news isn’t that good for the northern and southern resident orcas. The three northern clans number around 250, but the southern families who stay around south Vancouver Island, the Gulf Islands and the San Juans only number 70. They are endangered because their main diet of chinook, chum and coho salmon has declined, and the region’s heavy traffic and pollution also decrease their ability to breed and survive.

Yachties may well see increased numbers of different whales this year. But be warned. Washington law requires vessels to give southern resident orcas (the most endangered community) at least 300 yards (275 metres) of space. Boaters are also required to be at least 400 yards (365 metres) out of their path, or behind them.

For British Columbia, the federal Fisheries Act stipulates boaters must keep 100 metres away from all whales, dolphins and porpoises or 200 metres away if they are resting or with a calf. In addition, give a scope of 200 metres to killer whales. For the waters from Campbell River south to Ucluelet, the rules are even stricter: you must keep 400 metres away from all killer whales. And it’s not just a warning. A Prince Rupert diver who got way too close by trying to swim with orcas was fined $12,000.

14 • BC MAG

NATURE

DUE WEST

Pacific humpback.

IF I WERE asked to describe these 23 short stories in one word, it would be eclectic.

(And some of these short stories are very short indeed, like 1.5 pages). The book has been described as highlighting the particular magic of the West Coast, but while the stories are intrinsically BC, with many of them having a strong sense of place, it’s mostly not magic that’s highlighted.

We meet street people living rough in the bush (Delta Charlie); we meet tired middle-aged housewives in bars (Gelignite); we meet a teenaged girl in a small town (Buses come, buses go); we meet the author himself in a helicopter to hell (Into the Silverthrone Caldera) and as a firefighter (All the Bears Sing). I love the mix of people and places and I like that I never really know what Macy is going to write next. Mixed in

All the Bears Sing

By Harold Macy, Harbour Publishling, $24.95

By Harold Macy, Harbour Publishling, $24.95

REVIEWED BY CHERIE

THIESSEN

with these stories you can even find the occasional essay. (A Heartbreak of Winter Swans) and rants (Buried on Page Five). I think I can even include poetry in the mix as from time to time the language dances and pirouettes.

The author has published two previous books (The Four Storey Forest, 2011 and San Josef, 2020). His varied careers as heli logger, firefighter, and forester are mirrored in several stories and perhaps not surprisingly these are the ones I most enjoyed. When experience is melded with good writing it’s a winning combination.

Remember that BC tourism slogan: Super. Natural. British Columbia? The supernatural creeps in to a few stories as well, reminiscent of Dick Hammond. (A Touch of Strange: Amazing tales of the BC Coast).

BC MAG • 15

BOOK

Nairn Falls, just south of Pemberton.

Nairn Falls, just south of Pemberton.

DESTINATION

SPRING

DESTINATION PEMBERTON

A charming mountain town in the Garibaldi Range where the crowds are thin, adventure is high and the vibe is chill

BY DESIREE MILLER

TThe iconic Sea-to-Sky drive to Whistler is a well-known road trip for locals and tourists alike. However, for a remote getaway with a change of pace, keep driving. Continuing on Highway 99 just 30 minutes north will take you to the quaint little town of Pemberton. With a foundation built on forestry and agriculture (known for Pemberton potatoes) it’s a peaceful community that has evolved into a backcountry, off-road, mountain mecca for outdoor enthusiasts looking for a more rustic adventure.

The exploration begins just outside of town at Nairn Falls Provincial Park. This well-known pitstop features a 1.5-kilometre hike along the Green River that leads to the trail’s end where a stunning close-up view of Nairn Falls awaits.

BC MAG • 17

Andreas Prott

DESTINATION

Mountain biking on the Cream Puff trail near Pemberton, with Mount Currie in the background.

Destination BC/Reuben Krabbe

Some of the walking edges are exposed and there is a mix of steep and flat surfaces along the trek, but with that in mind, the trail is accessible to most. This can be a quick 40-minute round trip hike, or a place to stay for lunch and relax. The park itself is a great spot for spotting wildlife and taking in nature’s handy work of interesting rock formations formed by countless years of water erosion. The park also has a good provincial campsite that can serve as a base camp for exploring the area.

From here, it’s a five-minute drive to Pemberton where Mount Currie is the star of the show. As the main focal point of the valley, and with an elevation of 2,591 metres, this majestic mountain dominates the skyline. Known as Ts’zil in the St’at’imcets language this is the northernmost summit of the Garibaldi Range and is a mesmerizing presence in the valley.

Pemberton’s village centre is a casual wander by foot with a mix of local shops, restaurants, cafes, pubs and businesses. It’s a quick walk about, with enough to poke around for a feel of what life is like in this area. The General Store is the a great “little” department store, and offers a little bit of everything. It is fun to look around here to find the perfect item you need, or didn’t know you need. Another fun stop is the Pemberton Collective, which features creator and artisan made goods from all around BC, including pottery, jewelry, apparel and more. Small Potatoes Bazaar is an independent home and gift store with an eclectic mix of goods that reflects the laidback vibe of the area.

Pemberton also features some really

20 • BC MAG

DESTINATION 3 2 1

Top: Tourism Pemberton/Craig Barker; Above: Destination BC/Ben Girardi X2

good eats to check out. Backcountry Pizza is downright unreal. Possibly the best pizza available in the province, it is so amazing that you might want to plan more than one meal around these pies. Daily made dough and homemade sauce, golden brown crust cooked to perfection with cheese melting over the edges and high-quality, farm-fresh ingredients to top it off. Pro tip: leave a time buffer for your order, as busy nights can have a 45 to 60 minute wait.

Mount Currie Coffee Co. was created to reflect the small town feel and honour the adventurous spirit of the community. Fueling customers with a powerful kick-ass cup of coffee and a delicious selection of wraps and paninis, this has become a cult classic for locals and those passing through. For an epic start to the day try the breakfast panini featuring freshly baked focaccia style bread and a homemade pepper spread, shaved ham, cheese and fluffy scrambled eggs. The Pony, also known as the Pony Espresso, is a coffee shop and watering hole wrapped up in one. Featuring food that is locally grown and produced, they serve delicious meals and feature rotating taps. In the old train station in the centre of town is the Blackbird Bakery, serving homemade baked goods with locally sourced, organic and natural ingredients. Fresh breads of potato, ciabatta, baguette and creative creations are baked daily and served with coffee roasted in the Pemberton valley.

COUNTY ROADS

No doubt, a part of the romance of the area are the country roads that run through this mountain valley. The whimsical Pemberton Farm Tour is a lovely way to meander country roads as you hit-up each farm and get a taste of the area. From Pemberton centre,

BC MAG • 21 4

1. Beer Farmers Brewery during the Slow Food Cycle.

2. The Pony.

3. & 4. North Arm Farm.

SIDE TRIPS

Back Road Adventure

The Range Beyond Range Circle Route is a 284-kilometre back-road excursion that loops the rugged backcountry of the Coast, Cayoosh and Chilcotins, through the unceded ancestral lands of Lil’Wat Nation, St’at’imc Nation and the Tŝilhqot’in Nation. This circuit links Pemberton, Lilooet and the Bridge River Valley on a mix of paved and unpaved terrain for a deeper look into remote lands of British Columbia. This is a fourhour drive for those with a high-clearance four-wheel drive vehicle. Bringing a spare is recommended. For more in-depth guidance visit tourismpembertonbc.com/rangebeyondrange/

Train Wreck Hike

Off of Highway 99 before you hit Whistler, the Whistler Train Wreck mixes history, art and nature in this adventure with a twist. Seven box cars that were derailed in the 1950s are scattered in

the woods near the Cheakamus River. This interactive trek crosses a suspension bridge, winds through a rustic trail and ends on a site with the abandoned boxcars covered in colourful graffiti art. Climb in and over them and explore all around for an intriguing scene. Two of the cars further down the hill have lost their bottom and you can view the rushing river below. Access the trail east of Highway 99 on Cheakamus Lake Road.

Pemberton Meadows Road houses six different farms each with their own harvest and flavour. Blue House Organics, HappiLife Farm, Helmers Organic Farm, Laughing Crow Organics, The Beer Farmers and Plenty Wild Farms each feature unique specialties, seasonal fruits and veg, flowers, herbs, honey and ales.

Heading back to Highway 99 leads you to North Arm Farm with farm fresh breakfast served daily and a U-pick selection throughout the year. For those who want to start the day with a clear mind and soul, outdoor yoga at the farm is held periodically in spring and summer and overlooks Mount Currie. It is truly a unique and special experience. Kids of all ages can feed the resident sheep, chickens and pigs with bags of feed available for three dollars. Pemberton Distillery has farm-to-table spirits, including Pemberton potato vodka.

22 • BC MAG

DESTINATION

Top: Edgar Bullon/Dreamstime; Inset: Desiree Miller

Aerial panoramic view of the Duffey Lake Road between Pemberton and Lillooet.

EPIC SCENERY

Some say it’s the drive of a lifetime. The route from Pemberton to Lillooet is a coveted drive for those who seek roads less travelled. This is where Highway 99 becomes Duffey Lake Road and a series of switchback turns and single lane bridges overlook waterways, mountains, forests and thriving wild-

IF YOU GO

Lodging

Birken Lakeside Resort blrproperties.net

Pemberton Valley Lodge pembertonvalleylodge.com

Log house Inn loghouseinn.com

Food The Pony theponyrestaurant.com

Mile One Eating mileoneeatinghouse.com

Town Square Restaurant townsquarepemberton.com

Mount Currie Coffee mountcurriecoffee.com

Blackbird Bakery blackbirdbread.com

Hops & Spirits Pemberton Brewing pembertonbrewing.ca

The Beer Farmers thebeerfarmers.com

Pemberton Distillery pembertondistillery.com

Farms Plenty Wild

plentywild.ca

North Arm Farm northarmfarm.com

Happilife Farm happilife.ca

Blue House Organics bluehouseorganics.ca

Pemberton Farm Tour pembertonfarmtour.com

life. Enroute, you’ll pass iconic provincial parks such as Joffre Provincial Lake Park and Duffey Lake Provincial Park. It’s an hour and half drive nonstop from Pemberton to Lillooet, but trust me, you’ll want to stop. Experience first-hand the beauty of turquoise blue waters, glacier streams, sub-alpine forests and fresh mountain air. This is the utopia for hiking, mountaineering, fishing and wilderness camping. There is no gas station on this drive so be prepared!

BC MAG • 23

Farms

WHISTLER

PEMBERTON

Mount Currie

Birken Lakeside Resort

BIRKENHEAD LAKE PROV. PARK

Pemberton Meadows Road

Helmer’s

Laughing

North Arm Farm Plenty Wild Farms

Blue House Organics Happilife Farm The Beer Farmers LILLOOET LAKE

Organic Farm Nairn Falls Train Wreck Hike

Crow Organics Area of Enlargement Duffey Lake Rd. to Lillooet 0 7.5 15 Kilometres

99

99

Tasting room open year-round. A map of this self-guided tour can be found online at pembertonfarmtour.com.

HIT THE HILLS

Another draw to the area are the world class hiking and mountain biking trails. A series of trail networks are accessible from the Pemberton village as well as entry points throughout the valley. Some of the most epic views and luscious wilderness are a hike or bike away. It’s common to see a group

heading up for a ride. A google search will lead you to the area and experience most suited to you.

BC & THE ART OF MOTOR

RENTING A MOTORBIKE TO EXPLORE THE PROVINCE,

24 • BC MAG

STORY & PHOTOS BY ROBIN ESROCK

CYCLE MAINTENANCE

A NERVOUS WRITER BECOMES AN EASY RIDER

BC MAG • 25

If you’re driving behind a motorcycle on the highway and it passes another, pay attention.

You’ll notice that riders of all stripes greet each other with a subtle hand gesture. I saw it repeatedly as I rode the ocean road from Victoria to Port Hardy. Throttling down from Bella Coola to Williams Lake, traffic was sparse but the wave was always present. By the time I roared through the steep canyons of Highway 99 to Pemberton,

that wave became more than just an acknowledgement of how exhilarating it is to ride a motorcycle: it was a celebration of how fortunate we were to be riding this particular road, in this magical part of Canada. Across the country, the bike salute binds each rider into a Fellowship of Road Trips. Blink and you’ll miss it.

PERHAPS LIKE MYSELF, you don’t own a motorcycle and never have. Perhaps like myself, you’re drawn to the experience of riding a Harley Da-

vidson or a sport bike on some of the country’s most scenic roads. Perhaps you’re also nervous about high speeds, or taking dumb risks, or not willing to drop thousands of dollars on a bike you might only ride a few weeks a year. Luckily there are several companies in BC that offer motorcycle rentals, including Cycle BC, International Motorsports and EagleRider Rentals. I opted to rent a classic Harley Davidson Road King from EagleRider for roughly $100 per day, gas included, which was easier and more affordable than I

26 • BC MAG

expected to find my dream machine. Now I needed a road trip.

BIKERS FIND EACH other, because it’s fun and considerably safer to travel in groups. Riding in staggered formation, groups own the road and rarely get overtaken. I was fortunate to join (let’s avoid the word ‘crash’) an annual road trip of a regular group ranging in age from 24 to 60. They’d spent many months planning a trip north from their home base in Victoria, taking the 10-hour ferry to Bella Coola, and

returning south via Vancouver over five days. I met up with them heading north along the island’s Highway 19, getting familiar with the bike, lifestyle and landscape. I could smell forest earth and ocean salt, the new rain and tilled farmland. Road trips in cars put us in a closed box as the world passes by. On the motorbike, I found myself fully immersed, in the moment and constantly adjusting to the environment.

We roll into Dave’s Bakery in Campbell River, devour the best Reuben

Scenes from the journey, including a ferry ride from Port Hardy to Bella Coola.

sandwich on Vancouver Island, and discuss the trip ahead. Bikers are like anglers; eager to share war stories, technical tips, sage advice and the odd tall tale. All agree my Harley is the most powerful bike in the group, worthy of admiration and a fair amount of ribbing too. The Harley sub-culture deservedly tends to inspire both envy and ridicule.

We leave Campbell River and haul up the coast, traffic dissipating as the meandering asphalt cuts through endless forest. Rolling through small communities, each settlement feels more interesting than it does when seen through a car windshield. We constantly pull off to look at roadside attractions and viewpoints. Sometimes we open our throttles, sometimes we ride well below the speed limit in formation. Although my motorbike experience is limited at best, I feel comfortably safe in the leather saddle and grateful for my motorcycle’s forgiving clutch. We arrive in Port Hardy to spend the night in the excellent Indigenous-owned and operated Kwa’lilas Hotel. Feasting on memorable salmon-encrusted halibut in the adjacent pub, we look forward to the early morning ferry.

BC FERRIES’

NORTHERN

Sea Wolf is a 76-metre-long vessel offering yearround service between Port Hardy and Bella Coola. Taking just 35 cars and 150 passengers and crew, we’d reserved months in advance as the spacious ferry fills up in the summer months with RV’s and campers. We ramped on the 7:30 a.m. sailing, strapping our bikes down to counter strong waves that fortunately did not materialize. On the upper deck, we joined German, French, Dutch and local

BC MAG • 27

A road trip isn't a road trip without a breakdown somewhere along the way.

tourists taking in the extraordinary coastline, framed by King Island and soaring cliffs on the mainland. The captain made regular announcements about whale sightings and a humpback breached for us as if on cue. It’s a long, comfortable journey, with time to play cards, chat with travellers, gaze at the sea channel and look forward to the challenge ahead.

Bella Coola serves as a gateway to the Great Bear Rainforest, and a centre for bear-watching and outdoor adventure tours. We struck out early, anticipating issues along Highway 20’s infamous Hill. Full of switchbacks, steep inclines, single lane passes and hardpacked gravel, unseasonal wet weather had created long stretches of choppy mud. The hybrid off-road bikers in our group licked their lips, but I decided to call the cavalry. A friend in Williams Lake borrowed a trailer to help my Harley get over a notorious hill in horrendous condition. No need to be a hero. Although the motorcycle lifestyle promises renegade freedom, the truth is that most riders are not outlaws “Wanted Dead or Alive.” They’re wanted back in the office on Monday morning.

I REJOINED MY mud-baked group at the other side of The Hill, who confirmed the value of having good friends with trailers. We fuel up in Nimpo Lake, and speed out into a dramatically different landscape. It’s a long, wild biking day with everything: sun, rain, mud, curves, flats, horses, cows and the shadows of moose. Lush farmland, burned forests, snow-

capped peaks, marmots and mosquitoes the size of marmots. After 90,000 kilometres of reliable road trips, the Honda Shadow in our group rattled to a stop, defeated by age, mud and questionable mechanical maintenance. We arrange a tow to Williams Lake, divide up the saddlebags, invite the rider to hop onto the back of another bike, and start the debate of which bike he should buy—or rent—next. Every bike trip is an adventure and all agree you can replace a motorbike, but not a rider.

SOUTH FROM WILLIAMS Lake, the topography is more dramatic. Sage brush bristles in the breeze as we slowly snake through narrow mountain canyons carved by the mighty Fraser River. Dozens of bikers are gathered in Lillooet for the night, heading north or south. We admire machines, compare road conditions, and begin planning next year’s itinerary. East to Alberta? What about south into the US? It’s something to think about as we wind our way to Pemberton and onwards to Vancouver, riding the world-renowned Sea to Sky Highway. 1,800 kilometres and five incredible days later, I returned my bike that afternoon, greeting staff with a big smile.

Whether you used to ride, want a different ride or harbour a dream to ride the open road, renting motorbikes is an affordable, easy and magical opportunity. I already know what bike I’m going to rent next year. When you see me on the road, don’t forget to wave.

BC MAG • 31

Nothing connects a traveller to their surroundings quite like riding on a motorcycle.

ARCHIE’S GUIDE TO

HIGHWAY 37

EXPERIENCING THE WONDER OF BC’S NORTH

BY RICK HUDSON

BY RICK HUDSON

Northern BC Tourism/Andrew Strain

Archie says it’s a go, and he’s been driving the Stewart-Cassiar since, well, since the other Trudeau was Prime Minister. You can’t go wrong with my friend Archie. He knows a thing or two about Highway 37. He’s had more adventures there than Rick Mercer has had rants, and that’s saying something.

So, we’re heading north, leaving Highway 16 and the Lake District behind, and rolling into the great unknown. To us. To Archie, those 725 paved kilometres (give or take) are old hat and that’s why we’re going with him.

We start at Kitwanga after crossing the mighty Skeena River. It’s the second longest river fully in BC (after the Fraser) at an impressive 580 kilometres, but who’s counting, eh? The Skeena is an important salmon river, especially for sockeye, and starts way up north on the Spatsizi Plateau, where we’re headed. Which is where the Stikine, Nass and Dease rivers start too, only they go west, southwest and north, while the Skeena flows south. By the time it passes Kitwanga, the Skeena is well over halfway to the sea at Prince Rupert, and over 200 metres wide.

We fill up at the gas station on the corner of 16 and 37 and then drive over the Skeena bridge. Archie advises that the bridge was built in 1974, replacing the old rail and road bridge about a mile upstream. That one was built in 1925 and replaced a ferry service. “Progress,” says Archie, “it’s all about progress.”

The road itself has a good surface, and the traffic dwindles quickly, mostly just commercial trucks and the occasional RV

(like us). Highway 16 and 37 are a popular alternative to the Alaska Highway. It’s slightly shorter but no quicker. Mostly, it’s just different, and you’ll see a lot fewer vehicles than the other route. Plus, it visits some equally interesting places that in Archie’s opinion … but you don’t want to hear what Archie thinks. Right now, we’re rolling north and the road demands our full attention as one curve follows another.

AT GITANYOW WE turn left off the road and drive into the Gitxsan village where there are towering totems to be seen. During Covid, the village closed to outsiders and underwent a significant upgrade in roads, with much new paving. Open for tourism again, the village’s poles are special for a number of reasons. After the potlatch ceremonies were banned in the late 1800s, totems were carried off to many museums around the world. Many of the original Gitanyow poles ended up in the BC Museum in Victoria and were replaced with replicas, including the “Hole in the Ice” or “Hole in the Sky” totem that was erected in 1850. So, these are some of the oldest poles still standing. Marvel at the skilled craftsmanship, and know that each tells a story about origins, clan relationships, property rights or more.

It was here and in neighbouring Kispiox that artist Emily Carr painted some of her most famous totem canvases. The rows of traditional longhouses she recorded have gone, replaced by modern homes, but the aura remains. This is a special place. We park in front of the grocery store and wander around in quiet respect. Even Archie is silent.

The nearby Meziadin River has been the lifeblood of the Gitxsan people since time immemorial and Meziadin Lake up north is the heart of sockeye country. The lake is where a paved road runs west (the 37A) down to the coast at Stewart. “Not to be missed,” says Archie, so we gas up at the junction and turn to follow the setting sun over Bear Pass. The highway climbs 200 metres to Strohn Lake, where we pull off on the gravel verge and take a walk. There’s a westerly howling through the gap in the mountains, and the muddy

surface of the lake is being whipped into a steep chop.

Across the lake is the Bear Glacier. Archie cups his hands to his mouth so we can hear above the wind. “That ice has retreated a whole lot in just five years since I was last here,” he says. “Pretty soon it’ll be out of sight.” It drains the north side of Otter and Cambria peaks. Although the icefield above will still be there for

34 • BC MAG

A

decades, the white tongue of ice curving down to the lake—a great favourite with photographers—will be a thing of the past. Images from just a few years ago show the glacier at the lake; now, it’s melted upslope a long way.

IT’S RAINING IN Stewart, but that doesn’t detract from the small-town, friendly feel of the place. The old build-

ings along 5th Avenue still have a pioneer feel to them, reminiscent of the gold and silver mining heydays of yore. Check the excellent museum for a history lesson. At the Visitor Centre there’s help and suggestions on what to do, and next to the centre there’s a raised boardwalk out across the salt marshes of the estuary. On sunny days it provides spectacular views of the town’s situation, sandwiched be-

tween high peaks on either side (often snow-capped) and the Bear River. To the south, long, thin Portland Canal stretches 150 kilometres to the open sea; it’s the start of that great undefended 2,500 kilometre boundary between Canada and Alaska, all the way north beyond the Arctic Circle.

Just two kilometres down the road is the US border and the hamlet of Hyder

The Salmon Glacier is one of Canada’s largest. A 2WD road leads to a dramatic viewpoint above the ice, looking west to the boundary peaks along the Alaska border.

Tourism BC

(pop. 60 in the winter). Because there’s nowhere to go from there (more on that in a minute) it’s one of the very few entrance points where there’s no Uncle Sam waiting. But don’t forget to take your passport, because you’ll want to get back into Canada, and there is a Canadian Immigration post on your return!

When the salmon are running in midJuly to September, one of the north’s best experiences is just beyond Hyder at the Fish Creek Wildlife Observation Site. A raised walkway parallels the river, and it’s a favourite spot for bears to hunt pink and chum salmon. Hang over the rails and watch what’s happening below in relative safety. Signs remind you not to walk on the roads (bears walk on the roads) and to be careful getting out of your vehicle in the car park (bears wander through here too).

On that same road, and the highlight of many people’s trip to the region, is a visit to the Salmon Glacier at the head of the valley. It’s a 39-kilometre drive from Stewart through Hyder and up a long, switchback road. Archie doesn’t recommend it for RVs, but a competent 2WD vehicle will make it, with care. It’s an unpaved mine road that leads you back into the Canadian alpine (no border stops) and brings you out opposite the Salmon Glacier’s terminal. The guidebooks (and Archie) will tell you it’s the fifth largest in Canada. On a sunny day the view is extraordinary. The road transits above it, so you look down and across at a spectacular sweep of snow and ice that breaks up into crevasses and seracs at your feet. Bring warm clothes, cameras and lunch, to savour this natural wonder.

BACK AT MEZIADIN JUNCTION, it’s time to turn north again on Hwy 37. The highway follows a valley peppered with lakes on the west side. Many have provincial parks on them, but most are day-use or tent-camping only. Eighteenkilometre-long Kinaskan Lake is different. The south shore’s park has 50 RV sites, many with glorious views up the lake. Dawn and dusk produce some rich Kodak moments.

Just north of Kinaskan is Tatogga Lake. The Lodge is a must-stop if only to admire the mounted wildlife in the restaurant (the burgers are great too). We fall

into conversation with a staff member who explains all the things to do in the region, with the aid of a large wall map. For much of the summer, Alpine Air has a floatplane at the lake, providing access to a host of remote locales both to the west (Edziza Provincial Park) and the east (Spatzizi Plateau Wilderness Provincial Park). It’s important to call their head office (in Smithers) and plan ahead. The summers are short and there’s all-day pressure to fly passengers into the backcountry to hike, fish, hunt, kayak, raft or just camp. June to mid-August are the busiest times.

At the check-in counter we give our names, and the lady behind the desk comments, “That’s an unusual surname. I used to teach at College of New Caledonia with someone by that name.” She stares at our masks. Then the light goes on. “Joan?” “Bob?” They fall on each other like the old friends they were 30 years ago. There’s much laughter and ribbing as masks are pulled off and they recognize each other.

“What brings you here?” “We were hoping to get into the Edziza,” says Bob, “but the plane at Tatogga has gone south already.” Joan’s eyes twinkle. “Ours hasn’t.

The temperature’s down and it’s still raining. Our waiter at the restaurant explains that because of the forecast, the floatplane has already left for its base down south. Archie’s language is colourful at this news. We had plans to fly into the Spectrum Range for a couple of days.

But wait—Archie has a Plan B. There’s sometimes a Klappan Air floatplane at Kluachon Lake a bit further north. After lunch we drive the short distance on Hwy 37 and then down the steep gravel road to Mountain Shadow RV Park. We’re all wearing Covid masks out of courtesy to the locals, who often regard us as nothing more than disease-carrying scruffs from the south.

My husband Keith has his plane here. He’s busy, but not THAT busy.” Archie grins. It’s karma. Or luck. Whatever it is, we’re all pleased.

But summer is over, it seems, and the rain keeps falling for the next two days as we wait for a weather window. The temperature stays close to zero at the lake, and when the clouds lift on the third morning, there’s snow on the tops of everything. We were hoping to camp 600 metres higher than where we are, so it looks sketchy. We discuss the options back and forth as the rain continues. Joan reports the forecast is improving tomorrow.

Archie puts it best. “We’re here, now.

36 • BC MAG

Left: Between mid-July and September there’s excellent bear watching from a boardwalk at the Fish Creek Wildlife Observation Site. Right: The Gitanyow totem poles are some of the oldest in the province. Each records details of clan affiliations, or property title, legends or more.

Phillipa Hudson X2

Hazelton Kitwanga Gitanyow Kispiox Portland Canal Edziza Prov. Park SPATSIZI PLATEAU WILDERNESS PROV. PARK Smithers Kluachon Lake Mt. Edziza + Grand Canyon of the Stikine Morchuea Lake Upper Gnat Lake Dease Lake Cassiar Good Hope Lake Boya Lake/Tā Ch’ilā Prov. Park McDame Mountain + Watson Lake 97 Bear Glacier Fish Creek Wildlife Observation Site Salmon Glacier Stewart Hyder Meziadin Lake 37 37A Stewart Area of Enlargement 16 ALASKA B R I T I S H C O L U M B I A YUKON 0 30 60 Kilometres 37

Boya Lake in Tā Ch’ilā Provincial Park is famous for its turquoise waters, formed when pale marl (a limestone derivative) coats the bottom of the lake. In mid-summer the water is warm enough to swim.

Northern BC Tourism/Andrew Strain

Let’s make the most of the bad weather. We might not get to camp at 1,500 metres in ankle-deep snow, but we should make the effort to at least see the place.” We concur. Keith the pilot says he’ll take us flight-seeing.

THE NEXT MORNING dawns mostly clear, with fresh snow sparkling on the summits. The de Havilland Beaver climbs out of the valley, its rotary engine howling while Keith gives us a running commentary. He’s been a bush pilot, outfitter, hunter, helicopter base manager and married to Joan for over 50 years. He knows this territory like the back of his hand, and for the next hour and a half he shows us the wonders of the Edziza Plateau. By the way, it’s pronounced ‘edseye-za’. The name means ‘cinders’ in the Tahltan language.

The park has no vehicle access. It was established in 1972, and encompasses 2,660 square kilometres of complex volcanic terrain. It’s part of the line of volcanoes that stretch right up the west coast of North America and into Alaska. Earthquakes are not uncommon. A 7.7 magnitude quake occurred near Haida Gwaii in 2012. The park’s rocks are young—about 7.5 million years old— with recent minor eruptions forming perfectly symmetrical cinder cones, unblemished by the last Ice Age.

As the plane gains height, we swing around the south end of the plateau and the orange and red tones of the wellnamed Spectrum Range come into view under the right wing. Such colours—the rhyolite hues enhanced by the white of freshly fallen snow.

The summit of Mount Edziza (2,780

metres) is well glaciated. The south side, which gets the prevailing sun, is more broken and crevassed than its counterpart on the north. What comes across as we slip in and out of pockets of cloud, always keeping the peak on our right, is how wild and barren it appears. It’s sand, gravel and black basalt with little vegetation. Only at key passes between the radiating hills do we discern faint tracks where animals and hikers have crossed from one valley to another. Otherwise, the region appears supremely untouched, the way parks ought to be.

North of the main peak, long lava flows run down to the edge of the Grand Canyon of the Stikine. There, that 600-kilometre-long river squeezes into a slot so deep and narrow that it resembles a knife-cut through the plateau. Keith turns the plane and we follow it

40 • BC MAG

The weather finally cleared and bush pilot Keith Connors was able to take the group flightseeing from Kluachon Lake over Edziza Provincial Park.

upstream. In places it’s reported to be just three metres wide. Once considered ‘the last great problem of North American kayaking’ it was finally run in its entirety in 1990. However, such is the pace of extreme sports, 15 years later it was run in a single day. And in 2017, twice in a day! “There’s always one in the crowd,” says Archie.

WE’RE BACK ON the highway again.

As we drive away from Morchuea Lake, Archie observes that watersheds have always intrigued him. It’s not far before Hwy 37 crosses the Tanzilla River, which drains west into the Stikine and hence the Pacific Ocean. But just a short distance further we cross into a different catchment, where a raindrop starts its long journey via the Dease River into the Liard River, curving around the

north end of the Rocky Mountains and hence into the Mackenzie River, ending up in the Arctic Ocean—a journey of nearly 4,000 kilometres. Northern Canada is huge.

On the divide we reach the somewhat uninvitingly named Gnat Summit (1,241 metres) where there’s a spacious pullout next to Upper Gnat Lake. Happily, it’s too late in the season for bugs. The sun is out and the surface reflects the blue sky, with a new dusting of snow on the hills across the water. Loons call from the lake as it turns into an iconic northern evening.

Above the highway we see the abandoned bed of BC Rail’s northern construction, never completed. It was Premier W.A.C. Bennett’s dream to drive a rail line to the Yukon boundary, but it never happened. The cost of crossing

such complicated terrain turned out to be double the estimate. The project was finally shelved in 1978, having gone 300 kilometres beyond Prince George to Dease Lake.

Talking of Dease Lake, the next morning we halt there to gas up, but the Petro-Canada is more than just a fuel stop. The outfitter’s store has everything you would ever need to hang out in the north, from snowshoes and work boots to hunting and fishing gear and bug spray. Whatever you forgot to pack in the south, it’s likely they’ll have it, in three sizes and two different colours. This continues a longstanding trading tradition: Dease Lake town is close to a Hudson’s Bay trading post known as Lake House, founded in 1837.

The Telegraph Creek Road runs southwest from town. Under better

BC MAG • 41

The well-named Spectrum Range lies at the south end of Edziza Provincial Park. Sulphurous minerals in the rhyolite produce a variety of striking colours.

Phillipa Hudson X2

conditions we’d take the time to explore it, but bad weather and the fact there’s a washout and construction dissuades us from trying it this trip. It’s 112 kilometres of unpaved road and there are no services at the end. Be self-sufficient. If you think it’s tough driving, consider the great Canadian geologist George Dawson, who explored much of the region. It took him two and a half days on horseback to reach Telegraph Creek from Dease Lake back in 1887.

On the way down, at the confluence of the Stikine and Tahltan rivers is the Tahltan community. On the canyon wall across the river is an impressive basalt cliff known locally as Sesk’iye cho kime (pronounced ‘sis-kai-cho-kima’). It means ‘home of the crow.’ The bird’s spread wings are obvious; the feathers are comprised of vertical basalt columns, to dramatic effect.

Telegraph Creek has a population of about 250 permanent residents, and an interesting history. A prime fishing spot for the Tahltan First Nations, in the 1860s a telegraph company planned to use it as the start of an underwater cable to Europe (“That doesn’t make a blind bit of sense,” says Archie) via the Bering Strait, but lost out to a trans-Atlantic cable that ran from Newfoundland to Ireland—a considerably shorter distance. Nevertheless, the name ‘Telegraph Creek’ stuck. In the 1870s it became a starting point for numerous gold rushes to Cassiar, Cariboo and Klondike.

A DAY LATER we drive past Good Hope Lake and turn down at Boya Lake. The park was recently renamed Tā Ch’ilā Provincial Park, which means ‘blanket full of holes’—for the many bodies of water which fill the valley. There are 42 campsites, many on the lake. The water is a pale blue-green, lightened by dissolved white marl on the bottom, a result of erosion from upstream limestone peaks. It’s shallow and often warm, making for a rare swimming opportunity in the north. Canoe and kayak rentals are available from the Park Facilities Operator. Despite a moderately full campground, it feels like we have the whole

of northern BC to ourselves when we paddle among the islets. Recently gnawed aspens show where beavers have sourced their building material for a dam upstream. Archie advises there’s a local legend that says when the yellow swallowtail butterflies arrive at Boya Lake, the salmon are running at Tele-

graph Creek. There are many butterflies. A day or two later we drive the final 86 kilometres to Hwy 37’s junction with the Alaska Highway, aka Hwy 97. Just 23 kilometres east is Watson Lake; Whitehorse is 420 kilometres to the west. But Hwy 37 is over. “Well,” says Archie, “wotcha think, eh?”

Alexander Mackenzie passed the confluence of the Liard and Mackenzie rivers in 1789 and in 1803 a fur trading station was established there— later named Fort Simpson. In 1834, John Macleod reached the headwaters of the Dease River which was home to what today would be known as the Three Nations (Tahltan, Kaska and Tlingit peoples). He noted birds’ nests lined with yellow fibre, and fabrics woven from ‘mountain goat wool’ that didn’t burn. This was the unknown mineral asbestos.

In 1949, a Geological Survey of Canada expedition spent four days at McDame Mountain and positively identified the mineral, but due to its remoteness, assumed it wouldn’t be developed for decades. Yet that same winter a prospector sledded in and staked the first of many claims. The race was on!

With improved access via the Second World War-built Alaska Highway, the Cassiar Asbestos mine started, as the demand for this new wonder material rose. It was used in vehicle brakes, non-flammable cloth, high-strength concrete and house

insulation, to name just a few applications. Fibrous and fire-proof, it seemed to have an infinite number of uses.

An open pit mine started in 1951 under McDame Mountain, and the town of Cassiar followed, six kilometres to the south. By the 1970s, there was a population of 1,500 and a booming economy with schools, churches, a sports arena, a small hospital and even a theatre.

Mining was done by blasting in the pit, with the ore carried via tramline down to a mill. As they moved round the pit, miners noticed that one zone had a particularly hard rock which was of no apparent value. It was dumped, while the asbestos mining continued.

Jade was not a wellknown mineral back then, although a prospector, Bill Storie, had identified it on his claims on Wheaton Creek east of Dease Lake, in 1938. In 1967, one of the mine’s mechanics, a man named Clancy Hubble, who was also a rockhound, became intrigued by the hard rock waste. He sent a sample to the Dept. of Mines in Vancouver for analysis. The report confirmed it was nephrite

jade. The mine bosses had no interest in it, so Hubble got permission to stake the area where the waste had been dumped. He estimated there might be as much as a thousand tons of jade.

Within a few years the mine’s management began to realize their ‘waste’ was worth more per ton than their highgrade chrysotile asbestos! After some adjustments, most of the annual output (100 to 200 tons) was shipped to Taiwan. Initially, the buyers didn’t like the characteristic green chrome ‘fleck’ in the material, but later came to prefer it and paid a premium.

With rising concern about the link between asbestos and lung cancer, chrysotile sales began to drop in the 1980s. The need to stop open pit mining and go underground was an added financial hurdle. In 1992, Cassiar Asbestos closed. The mining equipment was sold off, as were buildings in the town, but most were simply dismantled, burned or buried. Today, a 12-kilometre drive west off Hwy 37 reveals another fascinating BC mining ghost town.

42 • BC MAG

THE CASSIAR MINE STORY

BC MAG • 43

Close to the highway, Upper Gnat Lake provides a wilderness campsite for RVs. Near this point a watershed divides the Pacific and Arctic ocean catchments.

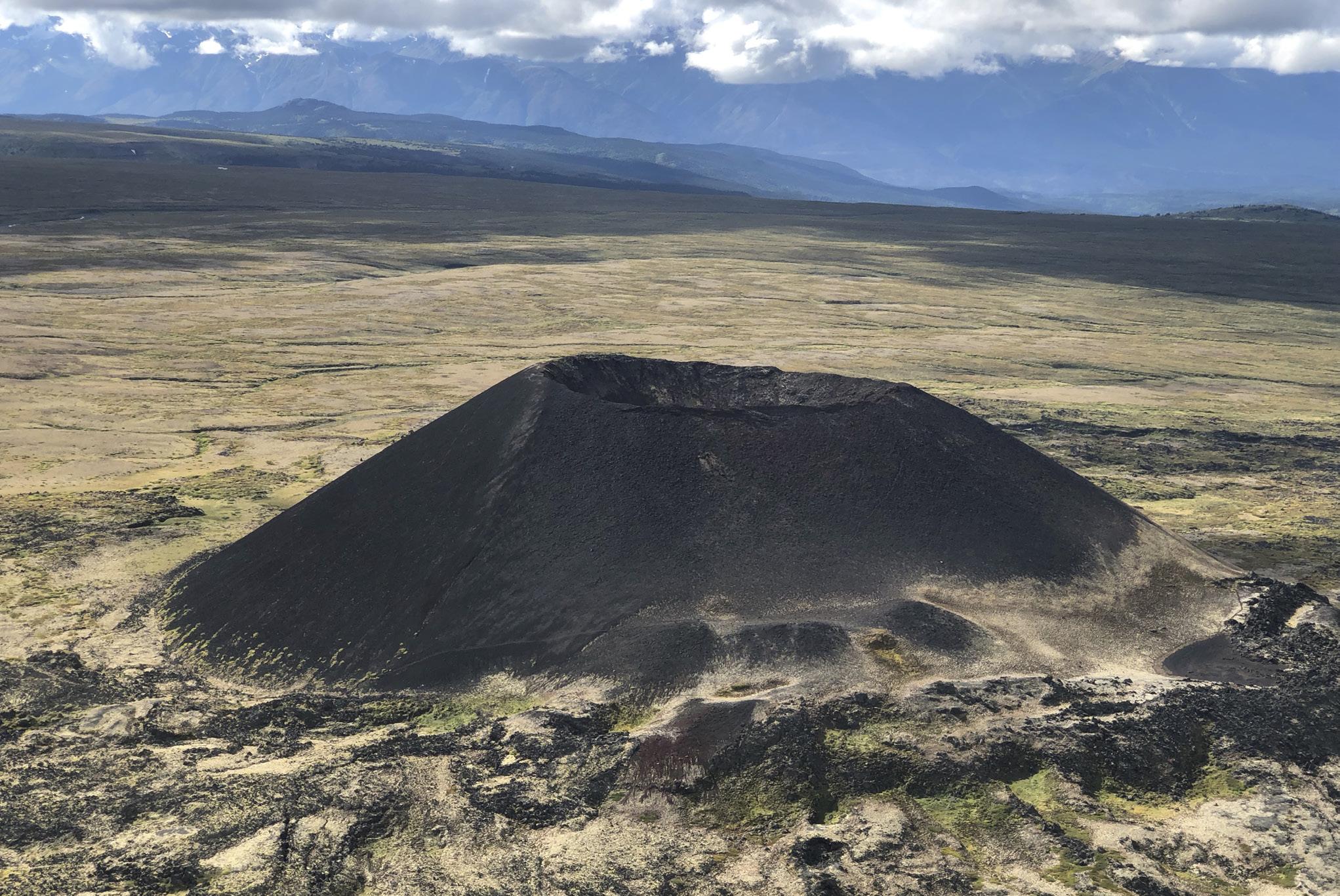

Recent volcanoes on the north side of Mount Edziza have symmetrical cinder cones. Barely 150 metres high and 1,300 years old, they remain unshaped by glacial erosion.

Phillipa Hudson X2

THE MUSKWA-KECHIKA: LAND OF LEGACY

COWBOY DREAMS FULFILLED IN THIS TWO-WEEK TREK THROUGH “THE SERENGETI OF THE NORTH”

BY JASON HARMAN

BY JASON HARMAN

Wayne Sawchuk

Wayne Sawchuk

The impudent brute clamped down on my little sausage fingers so hard that the entire North Island was subjected to my agonized wails.

But here’s the thing: I’ve always wanted to be a cowboy. It’s the whole ensemble—the hat, the leather, the swagger— but more than all that, it’s the freedom of the hills that has always appealed to me. The horse has only ever been an object, a necessary evil, a means to an end.

Given all that, it’s somewhat surprising that I now find myself perched atop a large mountain horse, surrounded flank-to-flank by 19 other large mountain horses and eight other riders, collectively careering into one of the remotest regions in North America. It’s my first day of a 14-day horseback expedition into the Northern Rockies of British Columbia, and all I can think is, “What the hell am I doing?!”

When I first heard stories about the Muskwa-Kechika—a 6.4-million-hectare area roughly the size of Ireland and twice the size of Vancouver Island— they sent chills up my spine. There is a place, the stories said, almost entirely roadless and undeveloped, where the air and waters are clean and pure, and the wildlife is so prolific that it is known as the “Serengeti of the North”—a true wilderness. Its name, spoken with reverence in a flowing half-whisper: muskquah-ke-chee-kah.

IF YOU HAVEN’T heard of the MuskwaKechika (or M-K), you’re not alone; most British Columbians haven’t either. Yet it is the largest contiguous wilderness area on the North American continent, surpassing even the likes of the Wrangell-Saint Elias, Mollie Beattie, Noatak, and Gates of the Arctic wilderness areas. The M-K comprises 50 undeveloped watersheds and a great abundance and diversity of species, including grizzly, moose, wolf, black bear, lynx, bull trout, grayling, caribou, elk, bison, mountain goat and stone sheep.

Translated, Muskwa means “bear,” and Kechika means “long inclining river.” (They also happen to be the names of two of the largest rivers that flow through the area.) The combination of its size, intactness, geographic diversity, and biodiversity makes it a truly exceptional place.

The horse I’m riding is a draft breed— a Belgian/percheron cross—named Anna. She is a friendly mare (or so the guides tell me), but she and I aren’t getting off to a great start. She is aloof and unresponsive to my requests. We do not see eye-to-eye. So far, we have both fallen over multiple times; she has run off midway through the mounting process; she has casually rammed me into several objects, including tree branches, tree trunks and other horses; and she has stood on my toes with her immense, metal-shoed feet. But, despite all that, she has successfully hauled my 230-pound frame through knee-deep mud, across numerous creeks and rivers, over fallen logs and up a few vertigoinducing mountainous inclines. She’s a working horse, I realize, and she’s getting the job done. Plus, given my aforementioned disdain for all things equine, I recognize that the problem likely rests with me. So, I implement a new strategy: sucking up. I feed her grass at every opportunity, pet her softly and whisper sweet nothings in her ear—peace by seduction is the goal.