WINTER 2023 HISTORYNET.COM WIWP-230100-COVER-DIGITAL.indd 1 10/3/22 11:18 AM

Each one of our 1:30 scale metal figures is painstakingly researched for historical accuracy and detail. The originals are hand sculpted by our talented artists before being cast in metal and hand painted – making each figure a gem of hand-crafted history. Please visit wbritain.com to see all these figures and more from many other historical eras. Mention this ad for a FREE CATALOG Free Mini Backdrop with your first purchase! matte finish Hand-Painted Pewter Figures 56/58 mm-1/30 Scale 31116 Confederate General “Stonewall” Jackson, No.2 $42.00 WBHN-WW WINTER-2022 ©2022 W.Britain Model Figures W.Britain, and are registered trademarks of the W.Britain Model Figures, Chillicothe, OH Follow us on Facebook: W-Britain-Toy-SoldierModel-Figure-Company Subscribe to us on YouTube: W.Britain Model Figures Tel: U.S. 740-702-1803 • wbritain.com • Tel: U.K. (0)800 086 9123 See our complete collection of 1/30 scale W.Britain historical metal figures at: 31380…$46 Confederate Infantry Bugler 31356…$45 Confederate Infantry Marching 10085 $45 Frederick Douglass American Abolitionist and Social Reformer 31392…$45 Federal Iron Brigade Advancing at Right Shoulder Wearing Gaiters 32005…$45 7th Cavalry Scout “Curly” 31350…$130 Three Federal Infantry Standing at Rest 31317…$42 Confederate General Robert E. Lee Confederate Infantry Waving ANV Flag 31372…$42 Federal in Frock Coat Standing Firing, No.3 31377 $45 Confederate Infantry Marching and Cheering 31361…$45 Confederate Infantry in Frock Coat Advancing Loading 10088 $45 Harriet Tubman American Abolitionist 32000…$45 Dismounted 9th Cavalry Trooper 32002…$45 U.S. Army Apache Scout, 1880s 32003…$45 Captain MylesKeogh 7thCavalry, 1876 32001…$45 U.S. Infantry on Campaign, 1880s 31381…$46 Federal Infantry Drummer, No.3 31267…$42 Confederate Infantry Kneeling Preparing to Fire 31177…$42 Confederate Infantry in Frock Coat Charging at Right Shoulder Shift, No.2 31086 $42 U.S. Colored Troops Marching 10086 $45 Sergeant Major Lewis Douglass, 54th Mass. Infantry WBHN-WW Winter-2022 Wild West.indd 1 9/28/22 2:07 PM WIWP-221108-006 Wbritain.indd 1 9/30/22 11:40 PM

History. Heritage. Craft CULTURE. The Great Outdoors. The Nature of the West.

million acres of pristine wildland in the Bighorn National Forest, encompassing 1,200 miles of trails, 30 campgrounds, 10 picnic areas, 6 mountain lodges, legendary dude ranches, and hundreds of miles of waterways. The Bighorns offer limitless outdoor recreation opportunities.

restaurants, bars, food trucks, lounges, breweries, distilleries, tap rooms, saloons, and holes in the wall are spread across Sheridan County. That’s 101 different ways to apres adventure in the craft capital of Wyoming. We are also home to more than 40 hotels, motels, RV parks, and B&Bs.

seasons in which to get WYO’d. If you’re a skijoring savant, you’ll want to check out the Winter Rodeo in February 2022. July features the 92nd edition of the beloved WYO Rodeo. Spring and fall are the perfect time to chase cool mountain streams or epic backcountry lines.

Sheridan features a thriving, historic downtown district, with western allure, hospitality and good graces to spare; a vibrant arts scene; bombastic craft culture; a robust festival and events calendar; and living history from one corner of the county to the next.

1.1

101

4

∞ WIWP Winter 2022-23 WIWP-221108-005.indd 1 10/4/22 1:31 AM

Engelhard

By Mark T. Smokov

Aaron Robert Woodard

Aaron Robert Woodard

HOW DEADLY WAS KID CURRY?

Harvey Logan was the Wild Bunch’s most prolific killer—or so legend has it ‘THE DEER IS LIKE MONEY’ By Michael

The herding of reindeer for food and fur was once a lucrative venture in Alaska THE SCOUT WHO STRADDLED TWO WORLDS By

Not even a murder charge could derail half blood Johnnie Bruguier’s Army career 40 48 32 WIWP-WINTER-2023-CONTENTS.indd 2 9/30/22 3:12 PM

Emmy Award–winning

EDITOR’S LETTER

LETTERS

ROUNDUP

INTERVIEW

BY JOHNNY D. BOGGS

Hill

WESTERNERS

Texan transplant Henry W. Strong

for Colonel Ranald S.

GUNFIGHTERS & LAWMEN

BY JULIA BRICKLIN

BY JULIA BRICKLIN

Judge William Story struggled as

Englishwoman

Widow Yetta Kohn

‘Hanging

PIONEERS & SETTLERS

BY JOHN H. MONNETT

Kingsley

WESTERN ENTERPRISE

BY JIM WINNERMAN

BY

ON THE COVER

In this oft-printed 1900 portrait five well-dressed members of the infamous Wild Bunch gang of outlaws—dubbed the “Fort Worth Five,” as they posed in that Texas town—happily sit still for photographer John Swartz. The reputed deadliest of the bunch, Harvey Logan (alias “Kid Curry”), stands at right beside Will Carver. Seated, from left, are Harry Alonzo Longabaugh (“Sundance Kid”), Ben Kilpatrick (“Tall Texan”) and gang leader Robert LeRoy Parker (“Butch Cassidy”). For more about the photo see historynet.com/last-word-famouswild-bunch-photo. (Denver Public Library, Photo Illustration by Brian Walker)

4

8

10

16

director Walter

talks Western movies and history 18

scouted

Mackenzie 20

the predecessor to

Judge’ Isaac Parker 22

Rose

recalled a slushy, happy Christmas 1871 in Denver 24

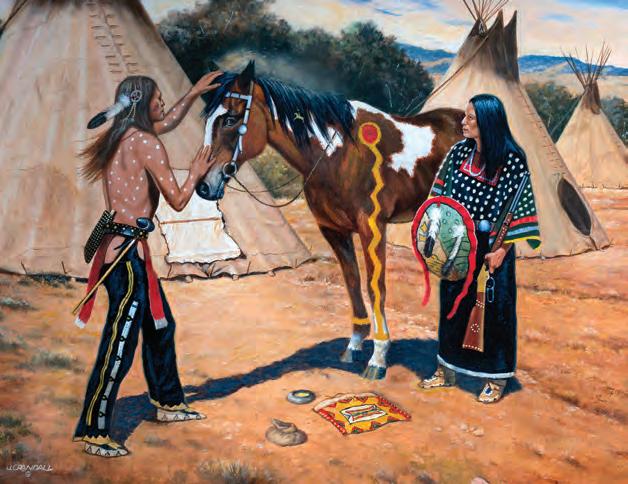

built a New Mexico Territory cattle ranch that’s still operating 26 ART OF THE WEST BY JOHNNY D. BOGGS Montana artist Jerry Crandall rendered award-winning Western art with accuracy 30 INDIAN LIFE BY RAMON VASCONCELLOS Few Indians benefited from the secularization of California missions in the 1830s 76 COLLECTIONS BY LINDA WOMMACK Fans of Lonesome Dove should plan a visit to Texas State University, San Marcos 78 GUNS OF THE WEST BY GEORGE LAYMAN Black Bart gained infamy for robbing stagecoaches—without firing his shotguns 80 GHOST TOWNS

JIM WINNERMAN Though Hawkinsville, Colo., hosted two gold booms, it never amounted to much 82 REVIEWS Award-winning author Johnny D. Boggs picks his favorite unsung nonfiction books and films. Plus reviews of recent books 88 GO WEST Some reindeer spend their ‘off-season’ receiving visitors at this Alaska farm A PEACE OFFICER MURDERED FOR BOOZE By Ellen Notbohm Even Paulson met a brutal death after surprising bootleggers in Mayville, N.D. THERE’LL BE A CATERWAULING IN THE OLD TOWN TONIGHT By Preston Lewis Hissing, growling and screeching feral cats caused nighttime distress out West 72 TROUBLE IN ZION By Will Gorenfeld An Army column pursuing Ute murderers in Utah Territory nearly sparked war 54 60 THE BUFFALO-BONE CANE MYSTERY By Matt Bernstein George Hearst awarded his protector Wyatt Earp with a walking stick—or did he? 66 WINTER 2023 WIWP-WINTER-2023-CONTENTS.indd 3 9/30/22 3:12 PM

When Earp Met Hearst

In case you missed it, a 2019 book published by the University of North Texas Press has proved a gift for those of us who can’t get enough information about the best-known of the “Fighting Earp” brothers. A Wyatt Earp Anthology: Long May His Story Be Told, edited by Roy B. Young, Gary L. Roberts and Wyatt biographer Casey Tefertiller, with a foreword by Wild West special contributor John Boessenecker, related enough stories about the legendary law man to help get me through a couple of self-isolated COVID years. “Earp’s un waning popularity led several genera tions of scholars, avocational historians and enthusiastic researchers to dig deep into his life and times,” writes Boessenecker. “The fruits of their labor appear here for the first time in a single volume.”

The anthology gives an overview of the man and the myth and details Wyatt’s life before, during and after his glorified days in Tombstone, Arizona Territory. Earp’s ride into the sunset was a long one; he was born on March 19, 1848, in Monmouth, Ill., and died at age 80 on Jan. 13, 1929, in Los Angeles. His life has been glorified by some (including in the popu lar 1950s TV series The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp), and he became known as the “Lion of Tombstone.” But in his earlier days an appropriate handle could have been the “Pimp of Peoria” (see Roger Jay’s groundbreaking story “‘The Peoria Bummer’: Wyatt Earp’s Lost Year” in the August 2003 Wild West). “Part VII [of the anthology],” writes Boessenecker, “presents a number of now-classic accounts that expose modernday authors who fabricated stories, and even some best-selling books, about Wyatt Earp.”

Of course, fabricated and/or overstated Wyatt tales have a rich history, going back to the two most famous early Earp books—Tombstone: An Iliad of the Southwest (1927), by Walter Noble Burns, and Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal (1931), by Stuart N. Lake—that portrayed Earp as a too-good-to-be-true guy. “Lake’s book…exaggerated the lawman’s deeds and created a sort of frontier superhero,” writes Tefertiller in “Finding Wyatt,” published in the October 2017 Wild West and reprinted in the anthology. One such hero-making tale Lake told is how in fall 1878 a courageous Wyatt confronted Clay Allison and ordered the dangerous shootist to literally get out of Dodge City, Kan. Rather than face the wrath of the stalwart lawman, the story goes, Allison complied. “It was preposterous,” writes Tefertiller.

Lake also claimed that in January 1882 (the gunfight near Tombstone’s O.K. Corral having occurred the previous Oc-

For anyone into Earpiana, A Wyatt Earp Anthology: Long May His Story Be Told is a must-read. Co-editors Casey Tefertiller and Gary L. Roberts have written the best biographies, respectively, of Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday. Their fellow editor, Roy B. Young, also wrote the insightful preface.

tober), Wyatt served as a bodyguard for Senator George Hearst, noting, “With Wyatt, Hearst spent a week riding and camping in the mountains and desert without molestation.” According to Lake, Hearst, who was on an inspec tion tour of Cochise County mining prop erties, had learned from an undercover Wells Fargo agent that Curly Bill, John Ringo and the rest of the Cowboy gang planned to kidnap and ransom him. In our feature story “The Buffalo-Bone Cane Mystery” (see P. 66) author Matthew Bernstein examines the Earp–Hearst association and in particular how Hearst supposedly gave Earp an Indian-made buffalo-bone cane (instead of money) for his services as a protector. After Wyatt’s death Lake wrote to newspaperman William Randolph Hearst, George’s son and heir, telling him the story (whether true or a Lake fabrication is open to question) of this walking stick. “Could it be Lake was trying to flimflam W.R. Hearst into buying a worthless stick of no historic value?” posits Bernstein before delving into the merits of Lake’s account. That the claim might be suspect is not surprising, consider ing the other tales Lake told in Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal

It didn’t help Lake’s claim, Bernstein notes, that the biog rapher repeatedly refers to Hearst as “Senator,” as Hearst wasn’t appointed to the U.S. Senate until 1886. Bernstein doesn’t go so far as to declare the Hearst–Earp cane chronicle “preposterous.” Whether true or not, it’s a story of interest that connects a self-made millionaire who established himself as one of the West’s most successful businessmen with the man who became the most famous lawman out West, even if he did it with a little help from friends and biographers.

Wild West editor Gregory Lalire’s historical novels include 2022’s The Call of McCall, 2021’s Man From Montana, 2019’s Our Frontier Pastime: 1804–1815 and 2014’s Captured: From the Frontier Diary of Infant Danny Duly His short story “Halfway to Hell” appears in the 2018 anthology The Trading Post and Other Frontier Stories .

WILD WEST WINTER 20234

EDITOR’S LETTER

WIWP-WINTER-2023-ED-LETTER.indd 4 9/30/22 9:08 AM

Western

walked taller than John Wayne. In

expected, so

Wayne” in two installments

$29.99, the first due before shipment,

$59.99*.

purchase is backed

money-back guarantee, so there’s no risk. Send no money now.

the

B_I_V = Live Area: 7 x 9.75, 1 Page, Installment, Vertical Price Logo Address Job Code Tracking Code Yellow Snipe Shipping Service Replica knife is richly adorned with hand-cast sculpture and portraits of the Duke on fine porcelain ® ©2022 BGE 01-02767-001-BIP Shown smaller than actual height of 10½ inches. Dull-edged replica knife is for decorative use only; not for use as a toy or weapon. JOHN WAYNE, , DUKE and THE DUKE are the exclusive trademarks of, and the John Wayne name, image, likeness and voice and all other related indicia are the intellectual property of, John Wayne Enterprises, LLC. (C) 2022. All rights reserved. www.JohnWayne.com YES. Please accept my order for the “John Wayne”® collectible as described in this announcement. Please Respond Promptly *Plus a total of $10.99 shipping and service; see bradfordexchange.com. Limitededition presentation restricted to 95 firing days. Please allow 4-8 weeks after initial payment for shipment. Sales subject to product availability and order acceptance. RESERVATION APPLICATION SEND NO MONEY NOW Where Passion Becomes Art The Bradford Exchange 9345 Milwaukee Avenue, Niles, IL 60714-1393 Mrs. Mr. Ms. Name (Please Print Clearly) Address City State Zip Email (optional) 01-02767-001-E56302 No

hero ever

five decades of Hollywood classics, Duke chewed up the Western landscape and proved himself a towering figure of honor and true grit. Now the strong-jawed hero rides across the range once more on a unique collectible that measures more than 10 inches in length and features riveting portraits on fine porcelain. A bronzed sculpt of John Wayne graces the hand-painted handle, further distinguished by the star’s replica autograph. Limited Edition. Order Today! Strong demand is

act now to acquire “John

of

totaling

Your

by our 365-day

Mail

Reservation Application today! ORDER TODAY AT BRADFORDEXCHANGE.COM/JWKNIFE WIWP-221108-010 Bradford An American Legend John Wayne Knife CLIPPABLE.indd 1 9/30/22 11:14 PM

ROB

DAVID

GREGORY

GREGORY

JOHNNY

JOHN

JOHN BOESSENECKER

BRIAN WALKER

MELISSA

PAUL FISHER

DANA B.

MICHAEL

CLAIRE

JAMIE

© TOMBSTONE TURMOIL , ANDY THOMAS VISIT HISTORYNET.COM Sign up for our FREE weekly e-newsletter at historynet.com/newsletters HISTORYNET PLUS! Today in History What happened today, yesterday or on any day you care to search. Daily Quiz Test your historical acumen every day! What If? Consider the fallout of historical events had they gone the ‘other’ way. Weapons & Gear The gadgetry of war—new and old, effective and not so effective. TRENDING NOW WINTER 2023 / VOL. 35, NO. 3 THE AMERICAN FRONTIER

J. LALIRE EDITOR

LAUTERBORN MANAGING EDITOR

F. MICHNO SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR

D. BOGGS SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR

KOSTER SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR

SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR

GROUP DESIGN DIRECTOR

A. WINN DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

ART DIRECTOR ALEX GRIFFITH PHOTO EDITOR

SHOAF MANAGING EDITOR, PRINT

Y. PARK MANAGING EDITOR, DIGITAL

BARRETT NEWS AND SOCIAL EDITOR CORPORATE KELLY FACER SVP REVENUE OPERATIONS MATT GROSS VP DIGITAL INITIATIVES

WILKINS DIRECTOR OF PARTNERSHIP MARKETING

ELLIOTT PRODUCTION DIRECTOR ADVERTISING MORTON GREENBERG SVP ADVERTISING SALES mgreenberg@mco.com TERRY JENKINS REGIONAL SALES MANAGER tjenkins@historynet.com DIRECT RESPONSE ADVERTISING NANCY FORMAN / MEDIA PEOPLE nforman@mediapeople.com © 2023 HISTORYNET, LLC SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION: 800-435-0715 OR SHOP.HISTORYNET.COM WILD WEST (ISSN 1046-4638) is published quarterly by HistoryNet, LLC, 901 North Glebe Road, 5th Floor, Arlington, VA 22203 Periodical postage paid at Tysons, Va., and additional mailing offices. postmaster, send address changes to WILD WEST, P.O. Box 900, Lincolnshire, IL 60069-0900 List Rental Inquiries: Belkys Reyes, Lake Group Media, Inc. 914-925-2406; belkys.reyes@lakegroupmedia.com Canada Publications Mail Agreement No. 41342519 Canadian GST No. 821371408RT0001 The contents of this magazine may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of HistoryNet, LLC PROUDLY MADE IN THE USA

MICHAEL A. REINSTEIN CHAIRMAN & PUBLISHER

The outlaw gang known as the Cowboys operated freely in Arizona Territory, until the Earp brothers and a friend named ‘Doc’ called their bluff. By John Boessenecker historynet.com/they-shoot-cowboys They Shoot Cowboys, Don’t They? WIWP-22-MASTHEAD.indd 6 9/30/22 12:54 PM

Centuries ago, Persians, Tibetans

gemstone of

Mayans considered turquoise

heavens, believing the striking blue stones were sacred pieces of sky. Today, the rarest and most valuable turquoise is found in the American Southwest–– but the future of the blue beauty is unclear.

On a recent trip to Tucson, we spoke with fourth generation turquoise traders who explained that less than five percent of turquoise mined worldwide can be set into jewelry and only about twenty mines in the Southwest supply gem-quality turquoise. Once a thriving industry, many Southwest mines have run dry and are now closed.

We found a limited supply of turquoise from Arizona and purchased it for our Sedona Turquoise Collection . Inspired by the work of those ancient craftsmen and designed to showcase the exceptional blue stone, each stabilized vibrant cabochon features

in Bali metalwork.

turquoise

*Special price only for customers using the offer code versus the price on Stauer.com without your offer code.

A.

B.

and

a

the

a unique, one-of-a-kind matrix surrounded

You could drop over $1,200 on a

pendant, or you could secure 26 carats of genuine Arizona turquoise for just $99 Your satisfaction is 100% guaranteed. If you aren’t completely happy with your purchase, send it back within 30 days for a complete refund of the item price. The supply of Arizona turquoise is limited, don’t miss your chance to own the Southwest’s brilliant blue treasure. Call today! 26 carats of genuine Arizona turquoise ONLY $99 C. Necklace enlarged to show luxurious color 14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. STC690-09, Burnsville, Minnesota 55337 www.stauer.comStauer ® Call now and mention the offer code to receive your collection. 1-800-333-2045 Offer Code STC690-09 You must use the offer code to get our special price. Rating of A+ Stauer… Afford the Extraordinary ® Jewelry Specifications: • Arizona turquoise • Silver-finished settings Sedona Turquoise Collection A. Pendant (26 cts) $299 * $99 +s&p Save $200 B. 18" Bali Naga woven sterling silver chain $149 +s&p C. 1 1/2" Earrings (10 ctw) $299 * $99 +s&p Save $200 Complete Set** $747 * $249 +s&p Save $498 **Complete set includes pendant, chain and earrings. Sacred Stone of the Southwest is on the Brink of Extinction WIWP-221108-014 Stauer Turquoise Collection.indd 1 9/30/22 11:36 PM

Cowboy Archaeologist

That was a wonderful article by Lynda Sánchez on George Mc Junkin [“Black Cowboy Archaeol ogist,” Pioneers & Settlers, Febru ary 2022], who opened up a whole new world in American history. I leased a ranch for years not far from the Folsom Site. One day I found a Folsom point, and now I don’t know where I put it. Your magazine is a good one. Keep it up.

Buddy Wolfe McCoy, Texas

TOM TOBIN

I thoroughly enjoyed the articles on Tom Tobin by the Leonetti brothers, Daniel and Robert, in the June 2022 Wild West.

It is fascinating to read stories about unsung characters from the Old West that are just as exciting as the ones we all know about. Halfway through reading I thought what a great movie the Tobin story would make. When I finished, I discovered Daniel is also a screenwriter. I sure hope some producer takes note of this.

“Texas Bob” Reinhardt Canyon Lake, Texas

WYATT & A RELIC

In the December 2021 Roundup the short piece “Six-shooters for [John] Boessenecker,” who wrote Ride the Devil’s Herd: Wyatt Earp’s Epic Battle Against the West’s Biggest Outlaw Gang, caught my attention, and I ordered his book, which I have just finished reading. It is the most concise and wellresearched book I have read on the Earps and the history of Tombstone and that corner of Arizona and New Mexico. When he describes events, I can see them in my mind’s eye. A story well told. It’s a great read.

I was born in El Paso in 1938 and raised through my child hood in southern New Mexico. My brothers and I lived at my grandmother’s in Vado, just north of El Paso, and went to school in Mesilla. Her first husband died in the Battle of Columbus when Pancho Villa attacked the town. My brothers and I rode horses and camped along the Rio Grande, where my grand mother owned a cotton farm. My family was not very verbal in passing on the history of my kin, and, sadly, I failed to ask questions. It was great to read the detailed history of the “Cow boy” period of the late 19th century and the ebb and flow of the lives of the Earps.

In my early 20s I was living in Phoenix and de veloped a love affair with ghost towns and all things of the Old West. I had hiked into what’s left of Charleston and camped overnight there in the 1970s. I have traveled the roads that run along the

Arizona and New Mexico border with Mexico. I’ve been in Contention City and stood on what remained of the old train platform and been to Shakespeare (ghost town) and the areas of Benson, Bisbee, Douglas and Silver City. I’ve hiked in the Chirica hua and Dragoon mountains. In the 1990s I found an old musket, sawedoff to carbine length, half buried in the floor of a cave south of old Fort Grant. Long ago it was ingeniously repaired with copper wire (from telegraph poles?). I believed the end users were probably Apache Indians.

Boessenecker brought to life for me not only the Earp his tory but also what it was like to have lived in that part of the Southwest at that time. It is a very thorough examina tion of the time and events and the lives of those who lived through it. Knowing more about the details of that history has certainly piqued my interest to revisit those places where I lived in the shadow of the frontier and its iconic stamp on our imaginations. Thanks again for the piece about Boes senecker’s book.

Everett Davidson Prescott, Ariz.

Editor’s note: Wild West special contributor John Boesseneck er not only won a Wild West History Association Silver Star in the best Western book category for Ride the Devil’s Herd but also captured a second Silver Star in the general Western history article category for “They Shoot Cowboys, Don’t They?” which appeared in the October 2020 Wild West and is available online at historynet.com/they-shoot-cowboys.

THEY SHOOT HORSES

I have a question nobody ever addresses: How many horses got shot under fleeing bandits? Seems it would be an efficient way to stop or slow the culprit. Can you answer me or put me in touch with someone that can?

Dennis Strong Salinas, Calif.

Send letters by email to wildwest@historynet.com Please include your name and hometown @WildWestMagazine

Gunfighter and lawman expert John Boessenecker responds: The whole idea of mounted posses racing on horseback after outlaws in a running gunfight is largely the invention of Hollywood. So, the answer is very few horses got shot under fleeing bandits.

WILD WEST WINTER 20238

LYNDA

A.

SÁNCHEZ COLLECTION

LETTERS

George McJunkin was not your average cowboy. Also an amateur naturalist, he discovered bones of the extinct buffalo species Bison antiquus at what would become the Folsom Site in New Mexico.

WIWP-WINTER-2023-LETTERS.indd 8 10/3/22 1:15 PM

Western Jacket

Expertly Crafted of Mohave-brown Cotton Canvas with Cotton Twill Lined Interior

Comfortable Sherpa Collar

Lay Down the Law in Rugged Western Style Just Like John Wayne

John Wayne’s legendary movie career included many heroic roles, including the tough, no-nonsense U.S. Marshall who would go to any length to bring his man to justice. Now you can wear a fitting tribute to this star of the silver screen with our ruggedly handsome Legendary John Wayne Western Jacket

This custom design offered only by The Bradford Exchange is inspired by the same jacket John Wayne wore in his classic role as a U.S. Marshall. Masterfully crafted of Mohave-brown cotton canvas with cotton twill lining, the jacket provides the ultimate in comfort and classic western style. The boldly styled jacket features a Sherpa collar and a double breasted front button closure. Faux leather patch embossed with a U.S. Marshall’s star along with John Wayne’s signature is sewn inside, proof that you’re a certified fan! The jacket has a roomy fit, 2 side flap pockets and an inside slip pocket with faux leather accent. It’s a great way to honor the enduring spirit of a true American icon! Imported.

An Outstanding Value… Satisfaction Guaranteed

This custom jacket is a remarkable value at $169.95*, and you can pay for it in 4 easy installments of $42.49 each. To order yours, in men’s sizes from M-XXXL (for sizes XXL and XXXL, add $10), backed by our unconditional 30-day guarantee, you need send no money now. Just fill out and mail in your Priority Reservation today!

B_I_V = Live Area: 7 x 9.75, 1 Page, Installment, Vertical Logo Address Tracking Yellow Shipping Service

JOHN WAYNE, , DUKE/THE DUKE are the exclusive trademark property of John Wayne Enterprises, LLC. The John Wayne name and likeness and all other related indicia are the intellectual property of John Wayne Enterprises, LLC. Design © John Wayne Enterprises, LLC. All Rights Reserved. www.johnwayne.com ©2022 The Bradford Exchange 01-29931-001-BIBR1

Inspired by the Jacket John Wayne Wore in His Role as a U.S. Marshall!

Embossed Faux Leather Patch with John Wayne’s Signature Sewn in at the Neck

NOT AVAILABLE IN STORES!

Order Now at bradfordexchange.com/29931 Connect with Us! PRIORITY RESERVATION SEND NO MONEY NOW Signature Mrs. Mr. Ms. Name (Please Print Clearly) Address City State Zip Email E56301 The Bradford Exchange 9345 Milwaukee Avenue, Niles, Illinois 60714 Where Passion Becomes Art ❑ Medium (38-40) 01-29931-011 ❑ Large (42-44) 01-29931-012 ❑ XL (46-48) 01-29931-013 ❑ XXL (50-52) 01-29931-014 ❑ XXXL (54-56) 01-29931-015 YES. Please reserve the Legendary John Wayne Western Jacket in the size checked below for me as described in this announcement. LIMITED-TIME OFFER PLEASE RESPOND PROMPTLY *Plus a total of $18.99 shipping and service (see bradfordexchange.com). Please allow 2-4 weeks after initial payment for shipment. Sales subject to product availability and order acceptance. WIWP-221108-011 Bradford John Wayne Sherpa Jacket CLIPPABLE.indd 1 9/30/22 11:15 PM

Favorite Living Western Artists

OF

Bob Boze Bell

The longtime editor of True West magazine has authored and illustrated biographies of such iconic Westerners as Billy the Kid, Wyatt Earp, Wild Bill Hickok and Doc Holliday. Bell is a gifted artist known for his surreal gouache paintings. “I’m just a cartoonist,” he says, “with strong opinions.”

Nocona Burgess

Immensely proud of his heritage, this great-great-grandson of Quanah Parker, the last Comanche war chief, is known for his bold acrylic paintings of Indian figures and culture and has moved into sculpture.

“My dad always said, ‘Every morning when I wake up, I thank God I’m a Comanche,’” the artist recalls.

Curtis Fort Born and raised on a working ranch in New Mexico, Fort might be as close to a modern-day Charles M. Russell as we’ll find, right down to his realistic bronze sculptures and cowboy drawl. Most of his works elicit a smile.

4

Dennis Hogan

An Indiana native, Gunsmoke fan and excellent worker of leather, silver and turquoise, Santa Fe–based Hogan pays homage to the past with a contemporary spin.

5

Douglas Magnus

Another Santa Fe–based silver smith, he creates high-end jewelry with a modern look and designs that evoke the past. In his “spare time” he dab bles as a photographer, videographer, plein air painter, etc.

6

Deana McGuffin

Those who don’t consider boot making an art form have never seen a pair of cowboy boots made by this Albuquerque legend who followed a path her grandfather forged in Roswell back in 1917. McGuffin will soon “retire” to try her hand at leatherwork and woodwork.

7

Barbara Meikle

Painter and sculptor Meikle is particularly drawn to that underappreciated hero of the American Southwest the donkey. Rife with humor, her

(2); REUTERS/ALAMY

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: MARSHALL GALLERY, SCOTTSDALE; THOM ROSS; BARBARA MEIKLE; ZUMA PRESS INC/ALAMY STOCK

HISTORICAL

UC BERKELEY; DAVID G. THOMAS;

FROM LEFT: BANCROFT

WILD WEST WINTER 202310

PHOTO

LIBRARY,

STATE

SOCIETY

NORTH DAKOTA 10

ROUNDUP

1

2

3

Bob Boze Bell

Thom Ross

Nocona Burgess

Barbara Meikle Curtis Fort

Deana McGuffin

WIWP-WINTER-2023-ROUNDUP-BW.indd 10 10/4/22 5:22 PM

oils and bronzes also capture horses, Western wildlife and landscapes. She donates part of her earnings to equine rescue efforts and animal shelters.

Billy on Trial

This quirky and highly opinionated San Francisco native loves the West, baseball and literature, not necessarily in that order. His offbeat interpretations of iconic Western figures challenge viewers. Ross’ most recent project tackles Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick.

8Thom Ross

9 Billy Schenck

On April 8, 1881, Billy the Kid finally stood trial in Mesilla, New Mexico Territory, for the April 1, 1878, murder of Lincoln County Sheriff William Brady in the town of Lincoln. He was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death by hanging. That sentence was never carried out, as he later escaped from custody at the Lincoln County Courthouse. On Aug. 13, 2022, Billy was on trial again—this time in a one-act play fittingly titled The Trial of Billy the Kid and presented at the Chiricahua Desert Museum’s Geronimo Event

After working with Andy Warhol in the mid-1960s, Schenck broke into the Contemporary Western/Southwestern Pop art scene with bold paintings inspired by late 1960s/early 1970s Spaghetti Westerns. He can hold forth about Western films for hours.

Don Yena This Navy vet goes all out to get everything just right in his paint ings. “I think the actual story of the American West is so fascinating,” he says from his studio in San Antonio, Texas. “I think it’s more exciting than fiction.”

—Johnny D. Boggs

For Whom the Bell Tolls

Swamped by a hurricane in the Atlantic Ocean some 160 miles off the coast of the Carolinas on Sept. 12, 1857, the 278-foot side-wheel steamship Central America sank with the loss of 425 of its 578 passengers and crew along with an immense cargo of gold (worth $765 million in today’s dol lars), much of it being transported to New York by men returning from the California Gold Rush.

Center in Rodeo, N.M. The Cochise County His torical Society and the Friends of Pat Garrett cosponsored the event, which drew a packed house of 200 people.

“The play fictionalized the real event,” said historian and filmmaker David Thomas, who wrote the feature article “The Trial of Billy the Kid” in the Autumn 2022 Wild West. “In the play Billy testified and had several witnesses testify in his defense. In the real trial the Kid did not testify and had no witnesses standing for him. Billy’s defense was that he had not killed Sheriff Brady, and, further, it was the cold-blooded mur der of John H. Tunstall that led to the violence in Lincoln the day that Brady was killed.” Despite the procedural differences, the outcome was the same—the jury found the Kid guilty.

—James McLaughlin, the agent at Standing Rock Indian Reservation, on the inter-Dakota border, wrote this in his annual report for the year ending July 31, 1883, about the great Hunkpapa Lakota leader Sitting Bull, by far the best-known Sioux on the reservation.

Commander William Lewis Herndon was justly credited with having safeguarded the lives of 153 passengers before going down with the ship. Be tween 1988 and 2014 expeditions to the wreck re covered gold and other artifacts from the seabed. Among the latter was Central America’s 268-pound bronze bell, which California business executive Dwight Manley recently donated to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md. At the heart of campus stands a granite obelisk in Herndon’s honor.

“The script compelled their decision,” Thomas said. The 15-member cast included the five pic tured above: (from left) Dan Crow as Judge Warren Henry Bristol, Kim Kvamme as prosecution witness Deputy Sheriff J.B. “Billy” Mathews, Bill Cavaliere (standing) as prosecuting attorney Simon B. Newcomb, Howard Topoff (seated out of view behind Cavaliere) as defense attorney Albert Jennings Fountain and Craig McEwan as the Kid. The Trial of Billy the Kid is scheduled to be performed at Schieffelin Hall in Tombstone, Ariz., on November 12 and at the Rio Grande Theatre in Las Cruces, New Mexico, on Feb. 25, 2023.

WILD WEST WINTER 2023 11

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: MARSHALL GALLERY, SCOTTSDALE; THOM ROSS; BARBARA MEIKLE; ZUMA PRESS INC/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO (2); REUTERS/ALAMY FROM LEFT: BANCROFT LIBRARY, UC BERKELEY; DAVID G. THOMAS; STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF NORTH DAKOTA WEST WORDS

10

‘I cannot understand how [Sitting Bull] held such sway over, or controlled men so eminently his superiors in every respect, unless it was by his sheer obstinacy and stubborn tenacity. He is pompous, vain and boastful and considers himself a very important personage’

WIWP-WINTER-2023-ROUNDUP-BW.indd 11 9/30/22 9:27 AM

Old West Town Resurfaces

In 1858 prospectors in California’s southern Sierra Nevada established a gold camp along the Kern River. It briefly went by the names Rogersville, Williamsburg and Whiskey Flat before becoming Kernville and qualifying for a post office in 1868. In the first half of the 20th century Kernville, some 35 miles northeast of Bakersfield, served as a backdrop for many Western movies, including John Ford’s 1939 classic Stagecoach, starring a young John Wayne. But in 1948, to solve flooding issues in Bakersfield, Congress acquired the land and appropriated funds to build the Isabella Dam, which the Corps of Engineers completed in 1953. By then Kernville had been razed, its residents forming a new Kernville on higher ground. Most years the original townsite remains well beneath 11,200-acre Lake Isabella—though it pops up, literally and in the news, whenever rain is scarce. During a recent drought the water level dropped enough to expose the foundations of old Kernville’s jail, a store, a school, a church and other structures. Townsfolk are happy to bid the past goodbye in favor of precious water.

Button Down

it

Marshal’

—Jack McCall, who murdered Wild Bill Hickok in Deadwood, Dakota Territory, on Aug. 2, 1876, spoke these words as U.S. Marshal J.H. Burdick cinched a noose around his neck atop the gallows in Yankton on March 1, 1877. As the trap was sprung at 10:10 a.m., McCall was heard to gasp, “Oh, God!”

Visitors strolling the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument this summer happened across a Civil War–era uniform cuff button bear ing an embossed eagle with outspread wings and a shield. Both Union and Confederate soldiers wore such buttons during the war. This exam ple may have been lost by one of Lt. Col. George

the artifact would go into the museum collection. Over the decades soldiers, passersby, archae ologists and park rangers have recovered some 26,000 artifacts from the battlefield, including weapons, ammunition and personal items.

Custer & Wild Bill

A Model 1873 Colt Single Action Army revolver issued to the 7th U.S. Cavalry on July 2, 1874, and reportedly recovered two years later from the Little Bighorn battlefield in Montana Territory realized $763,750 (well over the estimated high sale price of $550,000) at Rock Island Auction Co.’s May 13–15 Premier Firearms Auction. One of the Plains Indian warriors who prevailed over Lt. Col. George Custer and his immediate command on June 25, 1876, claimed to have col lected the revolver from the field of battle. In 1915

Armstrong Custer’s soldiers during the 7th U.S. Cavalry’s defeat at that Montana Territory battle field on June 25–26, 1876. That isn’t for certain, though, as such buttons were issued to enlisted men from 1855 to ’85. Its finders weren’t about to break federal law as keepers but left the button where it lay half-buried in the dirt. They took only photographs and reported their finding to park staff. While rangers didn’t indicate just where in the park the button turned up, they promised

he traded the pistol for a pair of pants and a blan ket, and the Colt remained in the trader’s family for generations.

The auction also featured an engraved Colt 1851 Navy revolver (Serial No. 204685) attributed to Wild Bill Hickok, which commanded $616,875 (nearly triple the estimated high sale price of $225,000). The Colt was once on display with its Navy mate (Serial No. 204672) at the Cody Firearms Museum in Cody, Wyo. They have match ing engraving and antique ivory grips, and both were manufactured in 1868.

Another Hickok revolver caused a stir at the Rock Island’s Aug. 26–28 Premier Firearms Auction. A Smith & Wesson Model No. 2 Hickok car ried—perhaps one he had on him when shot down by Jack McCall during a Deadwood, Dakota Territory, poker game on Aug. 2, 1876—brought a win ning bid of $235,000. While Hickok was most associated with the Colt 1851 Navy, later in life he favored the smaller, more accurate S&W No. 2. Other highlights of the August auction included an 1891 Colt Single Action Army that went for $763,750 and a Winchester Model 1873 “One of One Hundred” lever-action rifle that hammered down at $440,625.

WILD WEST WINTER 202312 FROM TOP: KVPICS, CC BY-SA 4.0; ROCK ISLAND AUCTIONS; LITTLE BIGHORN BATTLEFIELD NATIONAL MONUMENT, NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

FAMOUS LAST WORDS ‘Draw

tighter,

WIWP-WINTER-2023-ROUNDUP-BW.indd 12 10/3/22 2:17 PM

On May 18, 1980, the once-slumbering Mount St. Helens erupted in the Pacific Northwest. It was the most impressive display of nature’s power in North America’s recorded history. But even more impressive is what emerged from the chaos... a spectacular new creation born of ancient minerals named Helenite. Its lush, vivid color and amazing story instantly captured the attention of jewelry connoisseurs worldwide. You can now have four carats of the world’s newest stone for an absolutely unbelievable price.

Known as America’s emerald, Helenite makes it possible to give her a stone that’s brighter and has more fire than any emerald without paying the exorbitant price. In fact, this many carats of an emerald that looks this perfect and glows this green would cost you upwards of $80,000. Your more beautiful and much more affordable option features a perfect teardrop of Helenite set in gold-covered sterling silver suspended from a chain accented with even more verdant Helenite.

Limited Reserves. As one of the largest gemstone dealers in the world, we buy more carats of Helenite than anyone, which lets us give you a great price. However, this much gorgeous green for this price won’t last long. Don’t miss out. Helenite is only found in one section of Washington State, so call today!

Romance guaranteed or your money back. Experience the scintillating beauty of the Helenite Teardrop Necklace for 30 days and if she isn’t completely in love with it send it back for a full refund of the item price. You can even keep the stud earrings as our thank you for giving us a try.

Stauer… Afford the Extraordinary . ®

• 4 ¼ ctw of American Helenite and lab-created DiamondAura® • Gold-finished .925 sterling silver settings • 16" chain with 2" extender and lobster clasp Rating of A+ 14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. HEN435-01, Burnsville, Minnesota 55337 www.stauer.comStauer ® * Special price only for customers using the offer code versus the price on Stauer.com without your offer code. Helenite Teardrop Necklace (4 ¼ ctw) $299* .....Only $129 +S&P Helenite Stud Earrings (1 ctw) ....................................... $129 +S&P Helenite Set (5 ¼ ctw) $428* ...... Call-in price only $129 +S&P (Set includes necklace and stud earrings) Call now and mention the offer code to receive FREE earrings. 1-800-333-2045 Offer Code HEN435-01 You must use the offer code to get our special price. Uniquely American stone ignites romance Tears From a Volcano Necklace enlarged to show luxurious color EXCLUSIVE FREE Helenite Earrings -a $129 valuewith purchase of Helenite Necklace 4 carats of shimmering Helenite Limited to the first 1600 orders from this ad only “I love these pieces... it just glowed... so beautiful!” — S.S., Salem, OR WIWP-221108-012 Stauer Helenite Teardrop Necklace.indd 1 9/30/22 11:25 PM

L.Q. JONES

Craggy-faced character actor L.Q. Jones, 94, who featured in the Sam Peckinpah Westerns Ride the High Country (1962), Major Dundee (1965), The Wild Bunch (1969), The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970) and at least 55 other movies, died on July 9, 2022, at his home in Los Angeles. In the Budd Boetticher Western Buchanan Rides Alone (1958) his character defies an order to kill fellow Texan Tom Buchanan (portrayed by Randolph Scott), and in Hang ‘em High (1968) he slips a noose around the neck of Clint Eastwood. Born Justus Ellis McQueen Jr. on Aug. 19, 1927, in Beaumont, Texas, Jones also appeared in many 1950s–60s TV Westerns, including Cheyenne, Gunsmoke, Wagon Train and The Virginian. For a change of pace in 1975 he directed, produced and helped write the postapocalyptic comedy A Boy and His Dog

JAMES CAAN

Though perhaps best known for his role as Sonny Corleone in The Godfather (1972) or his portrayal of cancer-stricken Chicago Bears football player Brian Piccolo in Brian’s Song (1971), James Caan earlier made a notable appearance as the knife-throwing gambler “Mississippi” in Howard Hawks’ Western El Dorado (1966). Caan, who was born in New York City on March 26, 1940, died at age 82 in Los Angeles on July 6, 2022. In El Dorado Caan’s character sides with principal stars John Wayne and Robert Mitchum in a Western that is alternately gritty and amusing. He also appeared in such golden-era TV Westerns as Death Valley Days and Wagon Train

CLU GULAGER

The many TV roles of actor Clu Gulager, 93, who died in Los Angeles on Aug. 5, 2022, included his portrayal of a heroic Billy the Kid in The Tall Man (1960–62, with Barry Sullivan as Pat Garrett) and Deputy Emmett Ryker for four seasons (1964–68) of The Virginian. Born William Martin Gulager in Holdenville, Okla., on Nov. 16, 1928, he was an enrolled member of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. His paternal grandmother, Martha Schrimsher Gulager, was a sister to Mary America Schrimsher Rogers, the mother of humorist Will Rogers. In his final role Gulager appeared as a bookstore owner in the 2019 Quentin Tarantino comedy-drama Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.

Mankiller Quarter

The likeness of Wilma Mankiller (1945–2010), the first female principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, appears on the reverse of a new quarter coin, part of the U.S. Mint’s American Women commemorative program. Mankiller is depicted wearing a traditional shawl beside the seven-point star of the Cherokee Nation. A bust of President George Washington still graces the face of the coin. Other Indian women to have appeared on American currency include Pocahontas (on the reverse of a $20 bill in the 1860s) and Sacagawea (on the face of a dollar coin introduced in 2000 and first minted for general circulation in 2002).

Eye for Eye

L.J. Martin writes Western novels, nonfiction works and screenplays and is a co-founder of Wolfpack Publishing. He’s also a movie buff. But after 35 years Hollywood had yet to come calling, so he resolved to adapt one of his own novellas, Eye for Eye, into a recently released film. Filming was done on his ranch near Missoula, Mont. His executive producer is Hollywood public rela tions master David Mirisch, who brought aboard actors John Savage and Blanca Blanco. For the lead male role Martin picked friend and Montana native Shane Clouse, a songwriter and balladeer who also wrote the theme song. The film is avail able on Amazon Prime Video.

Carlyle Headstone

On Nov. 27, 1880, a posse out of White Oaks, New Mexico Territory, including deputized local black smith and ex-buffalo hunter James Carlyle, sur

rounded a roadside tavern known to locals as Greathouse Station. Trapped inside were sus pected rustlers, including Billy the Kid. At some point Carlyle set down his gun, went inside and tried to negotiate a surrender, but he was shot down. The posse lost interest and withdrew. The next morning locals found Carlyle’s body wrapped in a blanket and hastily buried in the frozen, rocky earth. A day later possemen returned, burned the tavern to the ground and exhumed Carlyle’s body. Placing it in a wooden box, they reburied it on a hilltop overlooking the smoldering ruins.

For 142 years only a mound of rocks marked the grave. All that changed on Aug. 5, 2022, when Carlyle got a headstone, thanks to the efforts of Lucas Speer, Jerry Prather and Josh Slatten, board members of Billy the Kid’s Historical Coalition (BTKHC). A short service followed, attended by members of BTKHC, Cold West, the Friends of Pat Garrett and the Wild West History Association.

WILD WEST WINTER 202314

LEFT, FROM TOP: EVERETT COLLECTION; WARNER BROS./GETTY IMAGES; EVERETT COLLECTION; U.S. MINT; RIGHT: JOSH SLATTEN

SEE YOU LATER... WIWP-WINTER-2023-ROUNDUP-BW.indd 14 9/30/22 9:29 AM

Notonly are these hefty bars one full Troy ounce of real, .999 precious silver, they’re also beautiful, featuring the crisp image of a Morgan Silver Dollar struck onto the surface. That collectible image adds interest and makes these Silver Bars even more desirable. Minted in the U.S.A. from shimmering American silver, these one-ounce 99.9% fine silver bars are a great alternative to one-ounce silver coins or rounds. Plus, they offer great savings compared to other bullion options like one-ounce sovereign silver coins. Take advantage of our special offer for new customers only and save $5.00 off our regular prices.

Morgan Silver Dollars Are Among the Most Iconic Coins in U.S. History

What makes them iconic? The Morgan Silver Dollar is the legendary coin that built the Wild West. It exemplifies the American spirit like few other coins, and was created using silver mined from the famous Comstock Lode in Nevada. In fact, when travelers approached the mountains around the boomtown of Virginia City, Nevada in the 1850s, they were startled to see the hills shining in the sunlight like a mirror. A mirage caused by weary eyes?

No, rather the effect came from tiny flecks of silver glinting in the sun.

A Special Way for You to Stock Up on Precious Silver

While no one can predict the future value of silver in an uncertain economy, many Americans are rushing to get their hands on as much silver as possible, putting it away for themselves and their loved ones. You’ll enjoy owning these Silver Bars. They’re tangible. They feel good when you hold them, You’ll relish the design and thinking about all it represents. These Morgan Design One-Ounce Bars make appreciated gifts for birthdays, anniversaries and graduations, creating a legacy sure to be cherished for a lifetime.

Order More and SAVE

You can save $5.00 off our regular price

buy now. There is a limit of 25 Bars per customer, which means with

Hurry.

GovMint.com • 1300 Corporate Center Curve, Dept. MSB183-01, Eagan, MN 55121

when you

this special offer, you can save up to $125.

Secure Yours Now! Call right now to secure your .999 fine silver Morgan Design One-Ounce Silver Bars. You’ll be glad you did. One-Ounce Silver Morgan Design Bar $49.95 ea. Special o er - $44.95 ea. +s/h SAVE $5 - $125 Limit of 25 bars per customer Free Morgan Silver Dollar with every order over $499 (A $59.95 value!) FREE SHIPPING over $149! Limited time only. Product total over $149 before taxes (if any). Standard domestic shipping only. Not valid on previous purchases. For fastest service call today toll-free 1-888-201-7144 Offer Code MSB183-01 Please mention this code when you call. SPECIAL CALL-IN ONLY OFFER Fill Your Vault with Morgan Silver Bars GovMint.com® is a retail distributor of coin and currency issues and is not a liated with the U.S. government. e collectible coin market is unregulated, highly speculative and involves risk. GovMint.com reserves the right to decline to consummate any sale, within its discretion, including due to pricing errors. Prices, facts, gures and populations deemed accurate as of the date of publication but may change signi cantly over time. All purchases are expressly conditioned upon your acceptance of GovMint.com’s Terms and Conditions (www.govmint. com/terms-conditions or call 1-800-721-0320); to decline, return your purchase pursuant to GovMint.com’s Return Policy. © 2022 GovMint.com. All rights reserved. Actual size is 30.6 x 50.4 mm 99.9% Fine Silver Bars Grab Your Piece of America’s Silver Legacy BUY MORE SAVE MORE! BUY MORE SAVE MORE! BUY MORE SAVE MORE! A+ WIWP-221108-016 GovMint Morgan Silver Bars.indd 1 9/30/22 11:18 PM

Hardly Over the Hill

EMMY-WINNING DIRECTOR WALTER HILL TALKS WESTERN MOVIES AND HISTORY

BY JOHNNY D. BOGGS

For a Hollywood director and screenwriter who came into the business around the time Westerns started to fade in popularity, Walter Hill has certainly made a name for himself in the genre, having received best director Emmy Awards for the pilot epi sode of HBO’s Deadwood (2004) and the two-part miniseries Broken Trail (2006). Broken Trail also earned Hill a Western Heritage Award from the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, as did his big-screen film Geronimo: An American Legend (1993).

The director of The Long Riders (1980) and Wild Bill (1995) will turn 81 on Jan. 20, 2023, but Hill isn’t slowing down. In 2021 he wrapped work as screenwriter and director of the forthcoming independently produced Western Dead for a Dollar, starring two-time Academy Award recipient Christoph Waltz. While filming near Santa Fe, Hill took time to discuss Western films and history with Wild West

What brought you to Dead for a Dollar?

It’s a script I’d been working on for about a year and a half, not c onstantly. There was a real historical character, Chris Madsen [a Denmark-born deputy U.S. marshal and one of Oklahoma Territory’s “Three Guardsmen” with fellow law men Heck Thomas and Bill Tilghman].…I thought the idea of a European immigrant as protagonist [Waltz as bounty hunter Max Borlund] was a nice, off-center way of getting into a story. We’re so used to the Joel McCrea, Randolph Scott, John Wayne Anglo kind of guy.

Yet you chose not to make it a Madsen biopic. No. Madsen’s intriguing, but the more I wrote, the less I pushed that idea. [Borlund] never was Chris Madsen. So I tried to give him his own point of view and distinct personality. Madsen was somewhat controversial.

How do you set about researching a film or character?

Reading Western history can be frustrating. A lot of it is incomplete, and an awful lot of it is contradictory. There’s very little backup for most of it. [Authors] quote local newspapers, which were notorious, for most of it. Trying to piece together who was a good guy, who was a bad guy in these historical char acters is, let me say, a rocky and narrow trail.

Do you enjoy history?

I like to read history. I was a his tory major and a lit minor. I can not tell you I was a great student.

Talk about Jesse James and The Long Riders.

I tried to emphasize certain things—that it was a Midwestern story, not a Western story; that they were farm boys, not cowboys. Some of the stuff I thought worked very well in the movie. But I don’t think it got to be a complete dramatic experience. David Carradine [as Cole Younger] was wonderful.

One of the best portrayals of Younger on film?

I really think so, yes.…The real Cole Younger wasn’t a lot like David Carradine. I’d be the first to tell you that. Probably the closest to what he was really like was Jimmy Keach’s Jesse.… He was a natural leader, and he was kind of crazy. They were all kind of afraid of him. When he said, “Let’s ride,” they rode.

What are your memories of filming Geronimo?

I have some complicated feelings about the movie.

I always said the title of the movie should have been The Geronimo War.

I wanted [viewers] to see the Army was a divided camp. In many ways the people who understood and were most sympathetic to the American Indians were members of the Army. Now, it wasn’t universally true by any means. Some of the most savage opponents were affiliated with the Army. [Lieutenant Charles] Gatewood [portrayed by Jason Patric] is…as [scout Al] Sieber said of him. He’s a sad case. He didn’t hate the enemy, and he didn’t love who he was fighting for.

I tried to use as much…of [Geronimo’s] dialogue recorded by what seemed to be reasonable sources of that time. His purported autobiography I don’t think is quite what the old man was thinking. But his last speech, on the train, which I wrote, was partially a cosmic understanding of the dilemma —that they weren’t going to win, and Geronimo says their time has passed. He meant their time as a dominant force. That’s not to in any way to forgive their treatment.

To read the full interview visit historynet.com.

WILD WEST WINTER 202316 UNITED ARTISTS

INTERVIEW

Walter Hill directs a scene from his 1980 Western The Long Riders while actors Duke Stroud (left) and Peter Jason, both playing Pinkerton men, await their cues.

WIWP-WINTER-2023-INTERVIEW.indd 16 9/30/22 9:30 AM

Order by Dec. 6 and you’ll receive FREE gift announcement cards that you can send out in time for the holidays! LIMITED-TIME HOLIDAY OFFER CHOOSE ANY TWO SUBSCRIPTIONS FOR ONLY $29.95 TWO-FOR-ONE SPECIAL! CALL NOW! 1.800.435.0715 PLEASE MENTION CODE HOLIDAY WHEN ORDERING SCAN HERE! OR VISIT HISTORYNET.COM/HOLIDAY Offer valid through January 8, 2023 * For each MHQ subscription add $15 Vicksburg Chaos Former teacher tastes combat for the first time Elmer Ellsworth A fresh look at his shocking death Plus! Stalled at the Susquehanna Prelude to Gettysburg Gen. John Brown Gordon’s grand plans go up in flames Tulsa Race Riot: What Was Lost Colonel Sanders, One-Man Brand J. Edgar Hoover’s Vault to Fame The Zenger Trial and Free Speech Yosemite The twisted roots of a national treasure HISTORYNET.com JUL 2020 H H HISTORYNET.COM JUDGMENT COMES FOR THE BUTCHER OF BATAAN THE STAR BOXERS WHO FOUGHT A PROXY WAR BETWEEN AMERICA AND GERMANY PATTON’S EDGE THE MEN OF HIS 1ST RANGER BATTALION ENRAGED HIM UNTIL THEY SAVED THE DAY In 1775 the Continental Army needed weapons— and fast World War II’s Can-Do City Witness to the White War ARMS RACE THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF MILITARY HISTORY An ammunition dump explodes during the April 1972 battle for An Loc. Defeating Enemy Stereotypes White and Black POWs bonded as cellmates The Green Berets Battles that inspired the book and movie TERROR AT AN LOC 9TH CAVALRY’S HEROIC FIGHT TO RESCUE DOWNED AIRMEN Huey Haven Old Warbirds Are Getting a New Museum HOMEFRONT Sweet success for Sammy Davis Jr. JUNE 2022 HISTORYNET.COM HNET SUB AD_HOLIDAY-2022.indd 1 8/30/22 8:34 AM

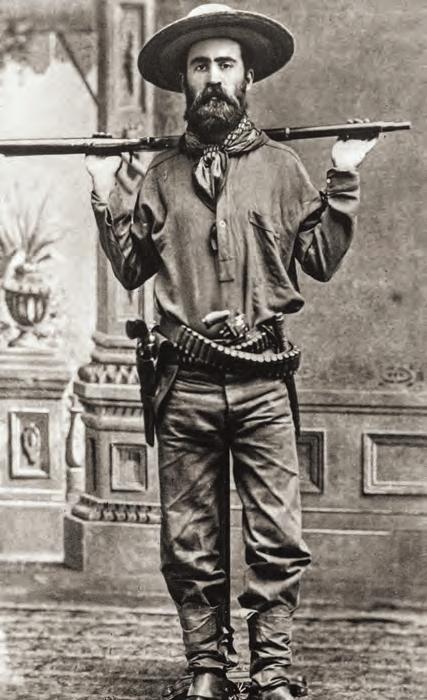

A Strongwilled Texas Scout

Ason of the South, Henry Woodson Strong wore many hats as a young adult in north east Texas, where he raised hogs and later sheep and in between served as a civilian scout and guide for Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie.

In 1926 he recounted his early days in the “Lone Star State” in his self-published 122-page memoir My Fronter Days and Indian Fights on the Plains of Texas

“The photo card is a card he would sign and give with the book,” collector Tony Sapienza says of this image.

“It’s rare to have the two together.” The author struck a different pose for the cover of his book. Born in Carroll County, Miss., on March 27, 1849, Strong grew up on his father’s turpentine plantation in Choctaw County, Ala. He briefly attended Spring Hill, a Jesuit college in Mobile, before joining a Confederate cav alry unit at age 15 and serving through the Civil War.

“He was an unrepentant Confederate,” says Sapienza. By 1870 Strong was in Texas and soon started raising hogs near Jacksboro. Around 1873, despite his Rebel sympathies, he signed on to scout for Mackenzie in his expeditions against renegade Comanches and Kiowas, doing battle and rescuing captives. On July 7, 1875, in the wake of the Red River War, Strong mar ried Sarah Eleanor “Pinkie” Parks in Wichita County, where in 1882 Henry began running sheep. By de cade’s end the Strongs, who ultimately raised seven children, had made Grayson County their home. In 1924 Pinkie died at age 70 in Waxahachie, the Ellis County seat. Oddly enough, though her husband sur vived her, the death certificate lists her as a widow.

On May 14, 1928, Henry, 79, died at the home of a niece in Palestine, the Anderson County seat. He’s buried in the Palestine City Cemetery.

TONY SAPIENZA COLLECTION

WESTERNERS

WILD WEST WINTER 202318 WIWP-WINTER-2023-WESTERNERS.indd 18 9/30/22 9:31 AM

It was a perfect late autumn day in the northern Rockies. Not a cloud in the sky, and just enough cool in the air to stir up nostalgic memories of my trip into the backwoods. is year, though, was di erent. I was going it solo. My two buddies, pleading work responsibilities, backed out at the last minute. So, armed with my trusty knife, I set out for adventure.

Well, what I found was a whole lot of trouble. As in 8 feet and 800-pounds of trouble in the form of a grizzly bear. Seems this grumpy fella was out looking for some adventure too. Mr. Grizzly saw me, stood up to his entire 8 feet of ferocity and let out a roar that made my blood turn to ice and my hair stand up. Unsnapping my leather sheath, I felt for my hefty, trusty knife and felt emboldened. I then showed the massive grizzly over 6 inches of 420 surgical grade stainless steel, raised my hands and yelled, “Whoa bear! Whoa bear!” I must have made my point, as he gave me an almost admiring grunt before turning tail and heading back into the woods.

But we don’t stop there. While supplies last, we’ll include a pair of $99 8x21 power compact binoculars FREE when you purchase the Grizzly Hunting Knife.

Make sure to act quickly. The Grizzly Hunting Knife has been such a hit that we’re having trouble keeping it in stock. Our first release of more than 1,200 SOLD OUT in TWO DAYS! After months of waiting on our artisans, we've finally gotten some knives back in stock. Only 1,337 are available at this price, and half of them have already sold!

•

•

•

I was pretty shaken, but otherwise ne. Once the adrenaline high subsided, I decided I had some work to do back home too. at was more than enough adventure for one day.

Our Grizzly Hunting Knife pays tribute to the call of the wild. Featuring stick-tang construction, you can feel con dent in the strength and durability of this knife. And the hand carved, natural bone handle ensures you won’t lose your grip even in the most dire of circumstances. I also made certain to give it a great price. After all, you should be able to get your point across without getting stuck with a high price.

The

Knife Speci cations:

Stick tang 420 surgical stainless steel blade; 7 ¼" blade; 12" overall

Hand carved natural brown and yellow bone handle • Brass hand guard, spacers and end cap

FREE genuine tooled leather sheath included (a $49 value!)

Grizzly Hunting Knife $249 $79* + S&P Save $170 California residents please call 1-800-333-2045 regarding Proposition 65 regulations before purchasing this product. *Special price only for customers using the offer code. 1-800-333-2045 Your Insider Offer Code: GHK184-02 Stauer, 14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. GHK184-02, Burnsville, MN 55337 www.stauer.com Stauer® | AFFORD THE EXTRAORDINARY ® A 12-inch stainless steel knife for only $79 I ‘Bearly’ Made It Out Alive What Stauer Clients Are Saying About Our Knives “The feel of this knife is unbelievable... this is an incredibly fine instrument.” — H., Arvada, CO “This knife is beautiful!” — J., La Crescent, MN 79 Stauer®Impossible Price ONLY Join more than 322,000 sharp people who collect stauer knives EXCLUSIVE FREE Stauer 8x21 Compact Binoculars -a $99 valuewith your purchase of the Grizzly Hunting Knife WIWP-221108-013 Stauer Grizzly Hunting Knife.indd 1 9/30/22 11:23 PM

Lest Ye Be Judged

On March 3, 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant nominated Story and Congress confirmed him to the bench of the new district court, which oper ated out of Fort Smith and was responsible for all federal legal matters occurring within its approximately 75,000-square-mile jurisdiction, from western Arkansas into Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). While Congress had split Arkansas into two federal districts in 1851, successive judges had presided over both until Story took the helm of the Western District.

The court struggled with the racial strife of Reconstruction and grappled with frontier law lessness amid disputes over Indian sovereignty and white settlement. It dispatched marshals into Indian Territory to arrest and bring to trial individuals accused of crimes. Yet so vast was the district, it could take days, weeks, sometimes months for lawmen to scour the boundaries of the territory and return with fugitives in tow. Complicating matters was the recurring question of jurisdiction—whether a suspect should be tried in an Indian court (of which there were several) or Story’s federal district court.

It was a plum assignment for Story, though newspapers in his home state of Wisconsin ex pressed doubts about the readiness of its young native. “That boy grew up without any particular aim in life, read law a short time in Milwaukee, provided himself with a carpet bag and went to Arkansas,” The Oshkosh Times wrote rather uncharitably. Though it deemed him “not very promising,” the paper said his family connec tions gave him “some degree of eminence.”

BY JULIA BRICKLIN

hen former federal judge and Colorado lieutenant governor William Story died in 1921, newspaper obituaries glossed over the most turbulent episode of his career. In 1874, under threat of impeachment, he had resigned as judge of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Arkansas. Before the court garnered headlines as the jurisdiction of Isaac “Hanging Judge” Parker and Deputy U.S. Marshal Bass Reeves, it was the domain of Story, a man considered by many contemporaries the most corrupt judge in the West.

W

Born in Waukesha County on April 4, 1843, Story earned a law degree from the University of Michigan in 1864. He may have been encouraged in his career choice by the memory of his paternal great uncle Joseph Story, who’d been an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. After serving in the Union Army during the Civil War, young Story practiced law in Wisconsin and Arkansas. In 1867 Governor Isaac Murphy of Arkansas appointed him as a judge in the state’s Eighth Judicial Cir cuit, in the southwest part of the state. Soon after taking office in 1869, Republican Governor Pow ell Clayton appointed Story to the bench of the Second Judicial Circuit, in northeastern Arkan sas. “The youngest judge of the grade in America is William Story, of the Arkansas court,” Wisconsin’s

WILD WEST WINTER 202320 LEFT: OLD STATE HOUSE MUSEUM, LITTLE ROCK; RIGHT: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

BEFORE RESIGNING IN DISGRACE, FEDERAL JUDGE WILLIAM STORY PRECEDED THE MORE CELEBRATED ‘HANGING JUDGE’ ISAAC PARKER IN ARKANSAS’ WESTERN DISTRICT

GUNFIGHTERS & LAWMEN

William Story was judge of the U.S. District Court for the newly created Western District of Arkansas till resigning under threat of impeachment in 1874. He later served as the seventh lieutenant governor of Colorado (1891 to ‘93) under Governor John Long Routt.

DENVER PUBLIC LIBRARY, COLORIZATION BY HISTORYNET WIWP-WINTER 2023-G&L.indd 20 9/30/22 9:32 AM

Janesville Daily Gazette trumpeted on Jan. 26, 1869. “He is 25 years old.”

Two years later came his appoint ment to the Western District, a plum position paying $6,000 a year, a hefty sum at the time. Taking up residence at the Metropolitan Hotel in Little Rock, 28-year-old Story went to work, hiring commissioners and marshals, and the papers soon reported he had his court up in “apple pie order” and running like “well-oiled machinery.”

Within a few months of his arrival, however, he fell dangerously ill. On June 17, 1871, the jurist overdosed on chloroform he’d reportedly pur chased and taken by mistake to alle viate a headache. It took a doctor several hours to revive him, and Story several days to fully recover. It was a harbinger of trouble to come.

Actively involved in Republican politics, Story had supported Arkansas’ First Dis trict congressman Logan H. Roots in the latter’s unsuccessful 1870 campaign for re-election. Roots had supported Story’s appointment to the bench, so the judge softened the blow of Roots’ defeat by hiring him as marshal of the Western District. Story also hired, as commissioners, two other men with whom he was politically aligned. Little more than a year after he took the bench, however, the U.S. attorney forced out Roots as marshal amid reports of fraud and soaring ex penses. One rival newspaper claimed the mar shal, with Story’s tacit approval, had dispatched deputies to round up sympathetic townsmen to vote for certain candidates in a local election. Meanwhile, local attorneys complained about Story’s two hired commissioners, accusing them of having withheld payments to witnesses who had often traveled hundreds of miles to appear in court, forcing some to sell personal effects to pay their expenses.

Story himself allowed marshals to charge the federal government for work they apparently never did, raising the question of whether he was getting kickbacks. “Parties who never left town,”

Little Rock’s Daily Arkansas Gazette reported, “were allowed and paid full fees of all kinds for hunting after prisoners, and some parties were allowed [and paid] for arrests made at a distance, when they did not leave town or make any ar rests.” Moreover, the paper alleged, Story signed blank vouchers and let marshals charge whatever they chose, without submitting proper receipts, a practice that cost taxpayers hundreds of thou

sands of dollars. Worse still, cases listed on some vouchers were fabrications. The attorneys also questioned Story’s handling of certain cases, par ticularly his decision to allow the release of one convicted murderer on bail before sentencing— a man who was neither pursued nor retried.

According to Story’s biographer, it was a May 1873 bribery charge that sealed his fate. The charge accused the judge of having accepted $2,500 to dismiss an indictment against an In dian Territory druggist for having illegally sold liquor to Indians. A U.S. attorney was accused of having accepted a $500 bribe to further guaran tee a dismissal in the case. Such accusations continued to swirl around Story and his court until finally, in early 1874, Congress started a for mal investigation. It ultimately charged him with 19 counts of corruption, notably the sale of his office for favors. Story appeared before the U.S. House Judiciary Committee, which found his ex planations for such alleged transgressions “lame, disconnected and unsatisfactory.”

Rather than face impeachment, Story resigned, on June 17, 1874. President Grant appointed Judge Parker in his place and tasked the “Hanging Judge” with reforming the federal court for the West ern District. Story moved his family to Ouray, Colo., where, despite the recent allegations of corruption, he built a successful law practice. In 1891, after a move to Denver, he was elected Colo rado’s lieutenant governor. In 1913 he relocated to Salt Lake City, where he resumed private law practice. Story eventually retired to Los Angeles, dying there at age 78 on June 20, 1921.

Above left: Arkansas Governor Isaac Murphy appointed Story as a judge in the state’s Eighth Judicial Circuit, in the southwest part of the state. Above: When Governor Powell Clayton took office in 1869, he appointed Story to the bench of the Second Judicial Circuit, in northeastern Arkansas.

According to Story’s biographer, it was a May 1873 bribery charge that sealed his fate

WILD WEST WINTER 2023 21 LEFT: OLD STATE HOUSE MUSEUM, LITTLE ROCK; RIGHT: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

DENVER PUBLIC LIBRARY, COLORIZATION BY HISTORYNET WIWP-WINTER 2023-G&L.indd 21 9/30/22 9:33 AM

Happy Christmas 1871!

PROPER ENGLISHWOMAN ROSE GEORGINA KINGSLEY REFLECTED ON THAT YEAR’S YULETIDE AMID DENVER SOCIETY

BY JOHN H. MONNETT

BY JOHN H. MONNETT

Memories of Christmases past run deep through the colorful history of Denver, among the first of the Great Plains settlements to urban ize. Englishwoman Rose Georgina Kingsley— eldest daughter of controversial Anglican priest, social reformer and writer Charles Kingsley and sister of Victorian novelist Mary St. Leger Kingsley (pseudonym Lucas Malet)—journaled one of the earliest recollections of how Denver ites celebrated yuletide.

In 1870 John Evans completed the Denver Pacific Railway, linking its namesake city to Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory, on the Union Pacific section of the transcontinental railroad. That same year William Jackson Palmer’s Kansas Pacific reached Denver. Their com pletion buoyed the flagging economy that had gripped post war Colorado Territory with the exhaustion of known placer

deposits, for the railroads made it possible to bring in industrial smelting and mining equip ment and thus exploit subterranean veins of gold and silver. Denver’s economy predict ably boomed, as did its affluent residential neighborhoods. The rails also brought wealthy Europeans fascinated by the prospect of seeing the Western frontier firsthand. Among them was Rose Kingsley.

Arriving on the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains just before Christmas 1871 to visit brother Maurice, a recent Denver transplant, Rose vividly described the sights and sounds of winter revelry. Her travels in Colorado Territory, which pre date those of her better-known countrywoman Isabella Bird by two years, brought Kingsley face to face with a territory and city on the verge of making their mark. Considering the florid writing of many Victorian-era authors, the straightforward

WILD WEST WINTER 202322 OPPOSITE TOP: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS; BELOW: THE KINGSLEY SCHOOL; THIS PAGE: NORTH WIND PICTURE ARCHIVES/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

PIONEERS & SETTLERS

“The streets are full of sleighs, each horse with its collar of bells,” wrote Rose Georgina Kingsley of yuletide Denver, where she arrived just before Christmas 1871 to visit her brother.

Rose Kingsley

WIWP-WINTER 2023-PIONEERS & SETTLERS.indd 22 9/30/22 9:33 AM

prose of Rose’s journal is refreshing. Consider the following description of her enchantment with the holiday activity around her:

Denver looks wintry enough under 6 inches to a foot of snow; but it is full of life and bustle. The toy shops are gay with preparations for Christmas trees; the candy stores filled with the most attractive sweetmeats; the furriers display beaver coats and mink, ermine and sable, to tempt the cold passerby; and in the butchers’ shops hang, besides the ordinary beef and mutton, buffalo, black-tailed deer, antelope, Rocky Mountain sheep, quails, par tridges and prairie chicken.

Strolling uptown from the commercial center along Blake Street, Kingsley entered Denver’s growing residential section along 14th Street past Larimer. “The streets are full of sleighs, each horse with its collar of bells,” she wrote, “and all the little boys have manufactured or bought little sleds, which they tie to the back of any passing cart or carriage and get whisked along the streets till some sharp turn or unusual roughness in the road up sets them.” The well-bred Englishwoman was particularly enamored with the unconstraint of Denver society. “In the frank, unconventional state of society which exists in the West, friendships are made much more easily than even in the Eastern states or, still more, in our English society.”

No Victorian Christmas Eve would be complete without a two-horse open sleigh ride. As the mer cury had dipped to 2 degrees below zero, Rose and Maurice bundled up beneath wool blankets, buffalo robes and plush sable furs. Leaving the city behind, the sleigh skimmed across the open prai rie beneath a bright moon, the horses fairly flying over the smooth, sparkling snow with silver bells jingling in the frosty air. When the siblings ar rived home around 11 p.m., Rose recalled, Maurice “looked just like Santa Claus, with his moustache and hair all snowy white from his frozen breath.”

Christmas Day dawned sunny and warm, leav ing Rose and Maurice to pick their way through rivers of melting snow to the Masonic Hall, tem porary home of the year-old Trinity Episcopal Church. Until their church building was com pleted several years later, British-born Anglican Denverites attended services at the hall, which on the outside reminded the English pastor’s daughter of a country squire’s coach house. Its interior had been tastefully decorated with fresh, fragrant evergreens from the mountains.

Following services Rose accepted an invitation to Christmas dinner at a fashionable home in

Denver was a busy place in the 1870s, as depicted in this hand-colored woodcut reproduction of a 19th-century illustration. There on Christmas Day 1871 Kingsley dined on turkey and mince pie, sang traditional carols and played such games as snap-dragon, in which players snatched up brandy-soaked flaming raisins.

which another friend boarded. After dinner of “the orthodox turkey and mince pie,” guests were summoned to the spacious parlor, where they gathered around a fresh spruce draped with strings of raw cranberries and popcorn. Once the host had distributed presents to his household servants, he and his guests passed the evening singing traditional carols and playing such games as blind man’s bluff and charades. Best of all was snap-dragon, the most popular of Victorian yuletide parlor games. Once the lights were dimmed, a shallow bowl filled with brandy-soaked raisins was set on the floor, and the liquor ignited. At a signal players took to snatching up flaming raisins from the bowl and popping them into their mouths. The idea was to close one’s mouth over a burning currant and extinguish the flame. One tradition held that the person who snatched up the most raisins would meet their true love within a year. Alas, Rose never married.

To end the near perfect evening, the master of the house gallantly began the first verse of “God Save the Queen.” Abashedly unfamiliar with the lyrics, he soon relinquished center stage to Rose. “It sent a thrill over me,” she wrote, “hearing it a thousand miles west of the Mississippi for the first time since leaving England. And then I was made to sing it all through; for, though the tune is familiar enough in America, no one present knew the right words.”

In 1874 Kingsley published her recollections of that memorable Denver Christmas in South by West: Or Winter in the Rocky Mountains and Spring in Mexico , edited by none other than father Charles, the Rev. Kingsley. Soon overshadowed by Bird’s 1879 masterpiece A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains, which many credit for the genesis of Colorado tourism, Kings ley’s book faded into obscurity, though it has since been reprinted. Follow ing statehood, of course, Colorado’s immigrant population multiplied, and present-day Denverites celebrate Christmas traditions from many lands, including merry old England.

WILD WEST WINTER 2023 23 OPPOSITE TOP: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS; BELOW: THE KINGSLEY SCHOOL; THIS PAGE: NORTH WIND PICTURE ARCHIVES/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

WIWP-WINTER 2023-PIONEERS & SETTLERS.indd 23 9/30/22 9:34 AM

The Widow Who Would Be Cattle Queen

AFTER HER HUSBAND’S UNTIMELY DEATH, YETTA KOHN JOINED FORCES WITH HER SONS AND DAUGHTER TO TAKE CARE OF BUSINESS IN NEW MEXICO TERRITORY

BY JIM WINNERMAN

In a discussion of life on the Western frontier relatively few women pop to mind. Even the well-known phrase “Go West, young man,” popularized by newspaper editor Horace Greeley, omits women from the story of west ward expansion. Certainly, women were there, often toiling away anonymously to raise families and crops in harsh envi rons. Yet few remain household names. Exceptions include hard-drinking, tough-talking Calamity Jane and, to a lesser extent, hard-drinking, quick-shooting Stagecoach Mary. One genuinely ladylike Western pioneer who has largely escaped notice is Yetta Kohn, who for decades in the late 1800s and early 1900s was a dynamic force on the plains of New Mexico (which became a state in 1912). A successful businesswoman, rancher and devoted mother, Kohn’s story has all the fabric of what constitutes an American legend.

A Jewish immigrant from Bavaria (born Yetta Louise Gold smith on March 9, 1843), she found success both as a young wife and mother and as a widow, and she did so without a formal education or parental guidance. Yetta’s very American story began in 1853, when the 10-year-old disembarked in New York from the steamer William Tell in the company of older family members, possibly siblings. They eventually made their way west, as Yetta’s name appears beneath theirs in the 1860

census as a 17-year-old resident of Leavenworth, Kansas Terri tory (admitted to the Union months later as the 34th state).

That year she married fellow countryman and Jewish immi grant Samuel Kohn, and the couple journeyed west in a covered wagon to start a new life together in gold rush–era Denver’s Cherry Creek neighborhood. There she gave birth to sons Howard and George, who as adults would become instrumental in Yetta’s later success. By 1865 the family of four had returned to Leavenworth, likely due to a flood that had devastated Cherry Creek in May 1864. Over the next several years Samuel entered the wool-and-hide business, and Yetta delivered three more children. Two died in infancy, while daughter Belle survived.