1848 Revolts That Changed America Zap! Railroads Get Electrified Brushstrokes of 19th-Century Life First Oil Boom: Drake Well in PA ‘All Men Are Created Equal’ Rare scrapbook reveals Lincoln’s early views on slavery HISTORYNET.com SUMMER 2023 AMHP-230700-COVER-DIGITAL.indd 1 4/6/23 11:43 AM

Personalized 6-in-1 Pen

Convenient “micro-mini toolbox” contains ruler, pen, level, stylus, plus flat and Phillips screwdrivers. Giftable box included. Aluminum; 6"L. 817970 $29.99

Personalized Garage Mats

Grease Monkey or Toolman, your guy (or gal) will love this practical way to identify personal space. 23x57"W.

Tools 808724

Tires 816756 $45.99 each

Personalized Super Sturdy Hammer Hammers have a way of walking o . Here’s one they can call their own. Hickory-wood handle. 16 oz., 13"L. 816350 $21.99

Personalized Extendable Flashlight Tool Light tight dark spaces; pick up metal objects. Magnetic 6¾" LED flashlight extends to 22"L; bends to direct light. With 4 LR44 batteries. 817098 $32.99

OFFER

AMHP-230516-011 Lillian Vernon LHP.indd 1 4/6/2023 12:23:59 PM

RUGGED ACCESSORIES FOR THE NEVER-ENOUGH-GADGETS GUY. JUST INITIAL

Personalized Grooming Kit

Indispensable zippered manmade-leather case contains comb, nail tools, mirror, lint brush, shaver, toothbrush, bottle opener. Lined; 5½x7".

817548 $29.99

Personalized Beer Caddy Cooler Tote Soft-sided, waxed-cotton canvas cooler tote with removable divider includes an integrated opener, adjustable shoulder strap, and secures 6 bottles. 9x5½x6¾". 817006 $64.99

Personalized Bottle Opener Handsome tool helps top o a long day with a cool brew. 1½x7"W. Brewery 817820 Initial Family Name 817822 $11.99 each

Personalized 13-in-1 Multi-Function Tool

All the essential tools he needs to tackle any job. Includes bottle opener, flathead screwdriver, Phillips screwdriver, key ring, scissors, LED light, corkscrew, saw, knife, can opener, nail file, nail cleaner and needle. Includes LR621 batteries. Stainless steel.

818456 $29.99

we’ll personalize them with your good name

Go to LillianVernon.com or call 1-800-545-5426. *FREE SHIPPING ON ORDERS OVER $50. USE PROMO CODE: HISAHIM3 LILLIANVERNON.COM/AHI The Personalization Experts Since 1951 OFFER EXPIRES 8/31/23. ONLY ONE PROMO CODE PER ORDER. OFFERS CANNOT BE COMBINED. OFFER APPLIES TO STANDARD SHIPPING ONLY. ALL ORDERS ARE ASSESSED A CARE & PACKAGING FEE.

Our durable Lillian Vernon products are built to last. Each is crafted using the best materials and manufacturing methods. Best of all,

or monogram. Ordering is easy. Shipping is free.*

HERE.

AMHP-230516-011 Lillian Vernon RHP.indd 1 4/6/2023 12:29:03 PM

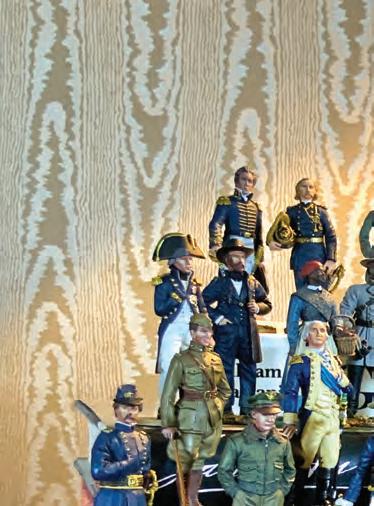

These sharp-dressed men are members of a Turnverein, an athletic club favored by 48ers.

54

AMHP-230700-CONTENTS.indd 2 4/6/23 11:40 AM

Summer 2023

30 L incoln in His Own Words

The rare scrapbook he shared with a friend on the campaign trail tells much of the man.

By Ross E. Heller

38 Going Electric

From puffing engines to crackling wires, American railroads put away the coal shovel and plugged in. By Richard

Brownell

Brownell

46 Color on Canvas

The racially pathbreaking 19th-century genre art of William Sidney Mount. By Katherine Kirkpatrick and Vivian Nicholson-Mueller

54 The 48ers

Fleeing oppression in their native lands, European revolutionaries brought their ideals to America.

By Raanan Geberer

A political poster for the 1944 election featuring President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Vice President Harry S. Truman. —see page 20

SUMMER 2023 3 FEATURES

38 46 30 DEPARTMENTS 6 Letters 8 Mosaic New Podcast Series 16 Innovations A Catcher’s Box? 18 A merican Schemers Wall Street Embezzler 20 Déjà Vu Unpopular Vice Presidents 24 Interview DAR Museum 26 A merican Place Keystone State Oil Boom! 29 Editorial 62 Terra Firma The Mighty Erie Canal 64 Reviews Sex and Murder 72 Toy Box Living Room Battleship

COVER:

CLOCKWISE FROM LEFT: MISSOURI HISTORICAL SOCIETY; FPG/GETTY IMAGES; SCHENECTADY MUSEUM ASSOCIATION/ GETTY IMAGES; LONG ISLAND MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART, HISTORY, & CARRIAGES; RIGHT: HERITAGE AUCTIONS; COVER: SEPIA TIMES/GETTY IMAGES/PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY BRIAN WALKER

ON THE

Abe Lincoln, scrapbooker? Yep. He tediously pasted newspaper clippings into a book. The 16th president still surprises.

AMHP-230700-CONTENTS.indd 3 4/10/23 11:15 AM

DANA B. SHOAF EDITOR IN CHIEF

CHRIS K.

A Union Commander's Shadow Legacy

By Judith Wilmot

Weapons

Gear

EDITOR

BRIAN WALKER GROUP DESIGN DIRECTOR

MELISSA A. WINN DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

JON C. BOCK ART DIRECTOR

CLAIRE BARRETT NEWS AND SOCIAL EDITOR

CORPORATE

KELLY FACER SVP REVENUE OPERATIONS

MATT GROSS VP DIGITAL INITIATIVES

ROB WILKINS DIRECTOR OF PARTNERSHIP MARKETING

JAMIE ELLIOTT SENIOR DIRECTOR, PRODUCTION

ADVERTISING

MORTON GREENBERG SVP Advertising Sales mgreenberg@mco.com

TERRY JENKINS Regional Sales Manager tjenkins@historynet.com

DIRECT RESPONSE ADVERTISING

NANCY FORMAN / MEDIA PEOPLE nforman@mediapeople.com

SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION: SHOP.HISTORYNET.COM or 800-435-0715

American History (ISSN 1076-8866) is published quarterly by HistoryNet, LLC, 901 North Glebe Road, Fifth Floor, Arlington, VA 22203 Periodical postage paid at Vienna, VA and additional mailing offices.

POSTMASTER, send address changes to American History, P.O. Box 900, Lincolnshire, IL 60069-0900

List Rental Inquiries: Belkys Reyes, Lake Group Media, Inc. 914-925-2406; belkys.reyes@lakegroupmedia.com

Canada Publications Mail Agreement No. 41342519, Canadian GST No. 821371408RT0001

© 2023 HistoryNet, LLC

The contents of this magazine may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of HistoryNet LLC.

PROUDLY MADE IN THE USA

NATIONAL ARCHIVES, PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY BRIAN

WALKER

MICHAEL A. REINSTEIN CHAIRMAN & PUBLISHER

SUMMER 2023 VOL. 58, NO. 2

HOWLAND SENIOR

Sign up for our FREE e-newsletter, delivered twice weekly, at historynet.com/newsletters HISTORYNET VISIT HISTORYNET.COM PLUS! Today in History What happened today, yesterday or any day you care to search. Daily Quiz Test your historical acumen every day! What If? Consider the fallout of historical events had they gone the ‘other’ way.

&

The gadgetry of war—new and old, effective and not so effective. TRENDING NOW Grenville Dodge was never a household name during the Civil War, but he quickly earned the esteem of Grant, Sherman, and Lincoln.

historynet.com/grenville-dodge-hero

AMHP-230700-MASTONLINE.indd 4 4/6/23 11:36 AM

Lives Remembered are never Lost

STEPHEN AMBROSE HISTORICAL TOURS PRESENTS

REVOLUTIONARY WAR: BOSTON TO QUEBEC

Travel with us September 24 - October 3, 2023

A TOUR YOU WON’T FORGET! Explore the origins of the American War for Independence, the battles that raged across the northern theater and the key players in that drama. They involved Patriots, Loyalists, Redcoats and Native Americans. We’ll walk battlefields where ragtag rebel forces clashed with one of the most feared armies in the world. We’ll meet the famous, the infamous, and the villainous figures who played out the dramatic struggle to forge a new nation. Our American History, Civil War and WWII tours are unrivaled in their historical accuracy!

EXPLORE NOW AT STEPHENAMBROSETOURS.COM 1.888.903.3329

AMHP-230516-008 Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours.indd 1 4/6/2023 11:06:47 AM

Future Plans

WITH APOLOGIES to our wonderful readers, the e-mail address we gave you to use last issue was not working properly, but it is now, so please send us letters! For now, enjoy this missive written by Robert Fulton, credited with inventing the steamboat, to George Washington. The first president was a firm believer in canals and was involved with the Patowmack Canal, vestiges of which remain on the Virginia bank of the Potomac River, above, and can be accessed by a hiking trail.

His EXCELLENCY GEORGE WASHINGTON. LONDON, February 5th, 1797.

Letters

SIR, – Last evening Mr. King presented me with your Letter acquainting me of the Receipt of my publication on Small Canals, which I hope you will soon have time to Peruse in a tranquil retirement from the Busy operations of a Public Life. Therefore looking forward to that period when the whole force of your Mind will Act upon the Internal improvement of our Country, by Promoting Agriculture and Manufacture: I have little doubt but easy Conveyance, the Great agent to other improvements will have its due weight And meet your patronage.

For the mode of giving easy Communication to every part of the American States, I beg leave to draw your Particular attention to the Last Chapter on Creative Canals; and the expanded mind will trace down the time when they will penetrate into every district Carrying with them the means of facilitating Manual Labour and rendering it productive. But how to Raise a Sum in the different States has been my greatest difficulty.

I first Considered them as National Works. But perhaps an Incorporated Company of Subscribers, who should be bound to apply half or a part of their profits to extension would be the best mode. As it would then be their interest to Promote the work: And guard their emoluments.

That such a Work would answer to Subscribers appears from such Informations as I have Collected, Relative to the Carriage from the neighbourhood of Lancaster, to Philadelphia. To me it appears that a Canal on the Small Scale might have been made to Lancaster for 120 thousand Ł and that the carriage at 20 shillings per ton would pay 14

thousand per annum of which 7000 to Subscribers and 7000 to extension. By this means in about 10 years they would touch the Susquehanna, and the trade would then so much increase as to produce 30,000 per annum, of which 15,000 to Subscribers, the Remainder to extension; Continuing this till in about 20 years the Canal would run into Lake Erie, Yielding a produce of 100,000 per annum or 50 thousand Ł to Subscribers which is 40 per cent.; hence the Inducement to subscribe to such undertakings.

Proceeding in this manner I find that In about 60 or 70 years Pensilvania would have 9360 miles of Canal equal to Bringing Water Carriage within the easy Reach of every house, nor would any house be more than 10 or 14 miles from a Canal. By this time the whole Carriage of the country would Come on Water even to Passengers -and following the present Rate of Carriage on the Lancaster Road, it appears that the tolls would amount to 4,000,000 per year. Yet no one would pay more than 21 shillings and 8d per ton whatever might be the distance Conveyed; the whole would also be Pond Canal on which there is an equal facility of conveyance each way. Having made this Calculation to Show that the Creative System, would be productive of Great emolument, to Subscribers, it is only further to be observed that if each State was to Commence a Creative System It would fill the whole Country, and in Less than a Century bring Water Carriage within the easy Cartage of every Acre of the American States, –conveying the Surplus Labours of one hundred Millions of Men.

Hence Seeing that by System this must be the Result, I feel anxious that the Public mind may be awakened to their true Interest: And Instead of directing Turnpike Roads towards the Interior Country or expending Large Sums in River Navigations – Which must ever be precarious and lead [no where] I could wish to See the Labour, and funds applied to Such a System As would penetrate the Interior Country And bind the Whole In the bonds of Social Intercourse.

The Importance of this Subject I hope will plead my excuse for troubeling you with So long a Letter, And in expectation of being Favoured with your thoughts on the System and mode of Carrying it into effect, I remain with the utmost Esteem and Sincere Respect,

Your most obedient Servant

ROBT. FULTON.

American History readers wanting to pillory, praise, or query the publication: write to us at americanhistory@historynet.com

BACKYARDBEST/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

AMERICAN HISTORY 6 AMHP-230700-LETTERS.indd 6 4/6/23 2:02 PM

Throw Yourself a Bone

Full tang stainless steel blade with natural bone handle —now ONLY $79!

Thevery best hunting knives possess a perfect balance of form and function. They’re carefully constructed from fine materials, but also have that little something extra to connect the owner with nature. If you’re on the hunt for a knife that combines impeccable craftsmanship with a sense of wonder, the $79 Huntsman Blade is the trophy you’re looking for.

The blade is full tang, meaning it doesn’t stop at the handle but extends to the length of the grip for the ultimate in strength. The blade is made from 420 surgical steel, famed for its sharpness and its resistance to corrosion.

The handle is made from genuine natural bone, and features decorative wood spacers and a hand-carved motif of two overlapping feathers— a reminder for you to respect and connect with the natural world.

This fusion of substance and style can garner a high price tag out in the marketplace. In fact, we found full tang, stainless steel blades with bone handles in excess of $2,000. Well, that won’t cut it around here. We have mastered the hunt for the best deal, and in turn pass the spoils on to our customers.

But we don’t stop there. While supplies last, we’ll include a pair of $99 8x21 power compact binoculars and a genuine leather sheath FREE when you purchase the Huntsman Blade

Your satisfaction is 100% guaranteed. Feel the knife in your hands, wear it on your hip, inspect the impeccable craftsmanship. If you don’t feel like we cut you a fair deal, send it back within 30 days for a complete refund of the item price.

Limited Reserves. A deal like this won’t last long. We have only 1120 Huntsman Blades for this ad only. Don’t let this beauty slip through your fingers. Call today!

Huntsman Blade $249*

Offer Code Price Only $79 + S&P Save $170

1-800-333-2045

Your Insider Offer Code: HBK144-01

You must use the insider offer code to get our special price.

Stauer ®

Stauer® 8x21 Compact Binoculars -a $99 valuewith purchase of Huntsman Blade

What Stauer Clients Are Saying About Our Knives

“This knife is beautiful!”

— J., La Crescent, MN

“The feel of this knife is unbelievable...this is an incredibly fine instrument.”

— H., Arvada, CO

Rating of A+

14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. HBK144-01 Burnsville, Minnesota 55337 www.stauer.com

*Discount is only for customers who use the offer code versus the listed original Stauer.com price.

California residents please call 1-800-333-2045 regarding Proposition 65 regulations before purchasing this product.

• 12” overall length; 6 ¹⁄2” stainless steel full tang blade • Genuine bone handle with brass hand guard & bolsters • Includes genuine leather sheath

Stauer… Afford the Extraordinary ®

today and

also receive this genuine leather sheath!

BONUS! Call

you’ll

FREE

EXCLUSIVE

AMHP-230516-004 Stauer-Huntsman Blade.indd 1 3/31/2023 2:47:30 PM

Working America

Mosaic

THE AMERICAN FOLKLIFE Center at the Library of Congress in March released its fourth season of “America Works,” a podcast series showcasing American workers in a diversity of jobs, careers, and life situations. The new series features stories from a cement plant worker, a grocery store cashier, a professional wrestler, a midwife, a herdswoman, and a neonatologist, among others.

Each “America Works” episode is based on a longer interview from the American Folklife Center’s Occupational Folklife Project, a multiyear initiative created to document work force culture.

Over the past 13 years, fieldworkers from the American Folklife Center have interviewed more than 1,800 working Americans, documenting their experiences in more than 100 professions. More than 600 of these full-length interviews are now available online.

“Our researchers are sending the Library so many great interviews with workers throughout the United States that it was hard to select just eight for Season Four. Despite the pandemic and a shifting economy, the humor, common sense, and pride reflected in these first-person accounts of working in America are inspiring,” said Nancy Groce, host of “America Works” and senior folklife specialist at the American Folklife Center.

The first three seasons of “America Works”— launched in August 2020, April 2021, and January 2022, respectively—are also available on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, and at loc.gov/podcasts.

OPPOSITE: PHOTO BY MELISSA A. WINN; THIS PAGE, TOP: NAITONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION; BOTTOM: COURTESY OF JAMESTOWN REDISCOVERY

A Day in the Life Joyce Godbout, a herdswoman and dairy farm manager, is featured in Season Four of the “America Works” podcast.

AMERICAN HISTORY 8 AMHP-230700-MOSAIC.indd 8 4/7/23 11:26 AM

Rare Lincoln Portrait Unveiled Archaeology at Jamestown

The National Portrait Gallery in February unveiled a rare portrait of President Abraham Lincoln. The nine-foot-tall portrait, painted by W.F.K. Travers in 1865, is one of only three known full-length renderings of the 16th president and will be on loan to the Smithsonian gallery in Washington, D.C., for the next five years.

The painting, which hung for decades in a municipal building in a small New Jersey town, has been restored and is now part of the “America’s Presidents” gallery.

Lincoln sat for Travers in 1864 and Travers completed the oil painting in Germany shortly after Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865. Travers then sold the painting to an American diplomat living in Frankfurt. In 1876, the painting was displayed at an exposition in Philadelphia, where Mary Todd Lincoln was reportedly, “so overcome by its lifelike appearance that she fainted and was carried out of the hall.”

For years, it hung in the U.S. Capitol while Congress considered whether to purchase it, but it was ultimately sold to the Rockefeller family. In the 1930s, Geraldine Rockefeller Dodge—daughter of William Jr. and niece of John D.—built the Hartley Dodge Memorial Building in memory of her deceased son and filled it with art, including the Lincoln portrait.

In 2017, an archivist discovered that a marble bust of Napoleon sitting in the corner of the council room of the Hartley Dodge Memorial Building had been sculpted by Auguste Rodin, prompting the foundation to reassess all of the art in its collection. The loan of the Lincoln portrait to the National Portrait Gallery is part of that reassessment.

In addition to Lincoln’s likeness, the painting is filled with symbols noting the president’s place in history. He stands in front of a bust of

George Washington and a rendering of the painting “Washington Crossing the Delaware” by Emanuel Leutze. Lincoln’s hand rests on a bound copy of the Constitution, next to a scroll bearing a draft of the 13th Amendment. Behind the scroll is a small statue of an African American man rising as he pulls the chains from his body.

Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists have been hard at work all winter on several projects, including work on uncovering the historic 20th century moat fill and the well-builder’s trench below to prepare for well excavation later this year. In February, archaeologists worked to take down the unit to the builder’s trench and fully expose the well surface. The archaeologists are using advanced photography and LiDAR scanning to create highly detailed models of the unit. The archaeology team also scans the area using Ground-Penetrating Radar. In March, archaeologists also opened a new unit in the North Field. They’re investigating the expansion of James Fort and Jamestown, looking for structures and landscaping features that would indicate where John Smith’s town of 50 houses was located.

Jamestown Rediscovery was launched in 1994 to find the site of the earliest fortified town on the

island and share the discovery with actual and virtual visitors. Within a few years, Jamestown Rediscovery uncovered enough evidence to prove the remains of James Fort existed on dry land near the church tower. A dozen staff members still excavate, interpret, preserve, conserve, and research the site’s findings. The team has mapped thousands of archaeological features, such as post holes, ditches, wells, foundations, graves, and pits.

OPPOSITE: PHOTO BY MELISSA A. WINN; THIS PAGE, TOP: NAITONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION; BOTTOM: COURTESY OF JAMESTOWN REDISCOVERY

SUMMER 2023 9 AMHP-230700-MOSAIC.indd 9 4/7/23 11:27 AM

Spero Takes the Helm at the Washington Presidential Library

What is It?

What was the purpose of this unusual tool?

Be the first to email the correct answer to dshoaf@historynet.com, subject heading “Home Building,” and your name will be posted with the description of the item.

The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association has appointed Patrick Spero, Ph.D., its new executive director of the George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon. Spero had been serving since 2015 as the librarian and director of the Library & Museum of the American Philosophi cal Society in Philadelphia.

“On March 9, 1797, 226 years ago today, George Washington departed Philadelphia for Mount Vernon after ending his second presidential term. I am thrilled to now head to Mount Ver non myself to start a new chapter as the George Washington Presi dential Library Director and to be a part of such an inspiring and dynamic place,” Spero said. “I am excited to grow its collections and develop new programs that expand knowledge of the life, leadership, and legacy of George Washington.”

Spero is the author of Frontier Country: The Politics of War in Early Pennsylvania (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), Frontier Reb els: The Fight for Independence in the American West (W.W. Norton & Company, 2018), and Botany and Betrayal: Andre Michaux, Thomas Jefferson, and the Kentucky Conspiracy of 1793 (Jeffersonian America series, University of Virginia Press, forthcoming Fall 2024), and co-editor of The American Revolution Reborn: New Perspectives for the 21st Century (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018).

Prior to his time at the APS, Spero served on the faculty of Williams College, teaching courses on American history and political leader ship. Spero is chair of the Executive Council of the McNeil Center for Early American Studies at the University of Pennsylvania; on the Board for the Consortium for the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine; on the Academic Advisory Board of the Benjamin Franklin House in London; and has served for many years on the Washington Library Cabinet at Mount Vernon.

The executive director of the George Washington Presidential Library fosters scholarship surrounding George Washington and his era, leads academic and public programs, and grows the library collection.

Spero will direct the center as it celebrates its 10th anniversary in September 2023, and charts the course for the decade, including the significant anniversaries recognizing America’s 250th in 2026 and George Washington’s 300th Birthday in 2032.

Answer to last issue’s What is It?

Congratulations to Bob Atnip, Westfield, Ind., who was the first to correctly identify a fire insurance plaque that was placed on a house. Stories have long circulated that if you did not have one of these, the fire department would not fight the fire. But it is more likely the plaques merely functioned as advertising for the insurance company.

TOP: ROBERT CREAMER, GEORGE WASHINGTON’S MOUNT VERNON, CC BY-SA 4.0; LEFT: GEORGE WASHINGTON’S MOUNT VERNON; RIGHT: NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION (2)

AMERICAN HISTORY 10 AMHP-230700-MOSAIC.indd 10 4/7/23 11:27 AM

Spero

5 Countries, 5 Pure Silver Coins!

Your Silver Passport to Travel the World

The 5 Most Popular Pure Silver Coins on Earth in One Set

Travel the globe, without leaving home—with this set of the world’s ve most popular pure silver coins. Newly struck for 2023 in one ounce of ne silver, each coin will arrive in Brilliant Uncirculated (BU) condition. Your excursion includes stops in the United States, Canada, South Africa, China and Great Britain.

We’ve Done

the Work for You with this Extraordinary 5-Pc. World Silver Coin Set

Each of these coins is recognized for its breathtaking beauty, and for its stability even in unstable times, since each coin is backed by its government for weight, purity and legal-tender value.

2023 American Silver Eagle: The Silver Eagle is the most popular coin in the world, with its iconic Adolph Weinman Walking Liberty obverse backed by Emily Damstra's Eagle Landing reverse. Struck in 99.9% fine silver at the U.S. Mint.

2023 Canada Maple Leaf: A highly sought-after bullion coin since 1988, this 2023 issue includes the FIRST and likely only use of a transitional portrait, of the late Queen Elizabeth II. These are also expected to be the LAST Maple Leafs to bear Her Majesty's effigy. Struck in high-purity

99.99% fine silver at the Royal Canadian Mint.

2023 South African Krugerrand: The Krugerrand continues to be the best-known, most respected numismatic coin brand in the world. 2023 is the Silver Krugerrand's 6th year of issue. Struck in 99.9% fine silver at the South African Mint.

2023 China Silver Panda: 2023 is the 40th anniversary of the first silver Panda coin, issued in 1983. China Pandas are noted for their heart-warming one-year-only designs. Struck in 99.9% fine silver at the China Mint.

2023 British Silver Britannia: One of the Royal Mint's flagship coins, this 2023 issue is the FIRST in the Silver Britannia series to carry the portrait of King Charles III, following the passing of Queen Elizabeth II. Struck in 99.9% fine silver.

Queen

Exquisite Designs Struck in Precious Silver

These coins, with stunningly gorgeous finishes and detailed designs that speak to their country of origin, are sure to hold a treasured place in your collection. Plus, they provide you with a unique way to stock up on precious silver. Here’s a legacy you and your family will cherish. Act now!

SAVE with this World Coin Set

You’ll save both time and money on this world coin set with FREE shipping and a BONUS presentation case, plus a new and informative Silver Passport!

BONUS Case!

2023 World Silver 5-Coin Set Regular Price $229 – $199

SAVE $30.00 (over 13%) + FREE SHIPPING

FREE SHIPPING: Standard domestic shipping. Not valid on previous purchases. For fastest service call today toll-free

1-888-201-7070

Offer Code WRD280-05

Please mention this code when you call.

SPECIAL CALL-IN ONLY OFFER

Not sold yet? To learn more, place your phone camera here >>> or visit govmint.com/WRD

GovMint.com® is a retail distributor of coin and currency issues and is not a liated with the U.S. government. e collectible coin market is unregulated, highly speculative and involves risk. GovMint.com reserves the right to decline to consummate any sale, within its discretion, including due to pricing errors. Prices, facts, gures and populations deemed accurate as of the date of publication but may change signi cantly over time. All purchases are expressly conditioned upon your acceptance of GovMint.com’s Terms and Conditions (www.govmint.com/terms-conditions or call 1-800-721-0320); to decline, return your purchase pursuant to GovMint.com’s Return Policy. © 2023 GovMint.com. All rights reserved.

GovMint.com • 1300 Corporate Center Curve, Dept. WRD280-05, Eagan, MN 55121

AMHP-230516-006 GovMint 2023 World Silver Coin Set.indd 1 3/28/23 1:57 PM

Against the Odds

On April 3, Civil War Trails unveiled a new sign at the first Civil War Trails site that champions the story of Jewish soldiers. Located at the Love Hope Center for the Arts in Fayettville, W.Va., it tells the story of men under the command of future-President Rutherford B. Hayes who were camped in the wilds of West Virginia and managed to pull together all the items required to properly observe the Passover holiday in 1862.

“In the midst of our nation’s darkest hour, these soldiers came together, enabled by the larger community and in doing so they offered peace and hope to a nation at war,” said Drew Gruber, executive director of the Civil War Trails program.

The project is the result of several years of dedication by local historians, Temple Beth El in Beckley, Love Hope Center for the Arts, and the New River Gorge Convention and Visitors Bureau. Dr. Joseph Golden, Secretary of the Temple Beth El congregation reads from the soldier’s diaries during their own Passover celebrations and has also researched the story of the 1862 Seder. Despite being a historic story, it rings true for the Jewish community today.

“Commemorating this Passover Seder celebrated by 20 Jewish Union soldiers has importance to the Jewish community in Fayette and Raleigh Counties. Although they were a minority in the Union Army, they were and we are part of the diverse fabric that make up this nation” said Dr. Golden.

This 1865 manuscript broadside of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery in the United States, is signed by then-Vice President Hannibal Hamlin and 111 congressmen. It’s one of a handful of commemorative copies circulated in the halls of Congress for signatures.

The amendment passed the Senate with 38 votes in April 1864, but then faced a long fight in the House. Months later, on January 31, 1865, it barely reached the necessary two-thirds in the House of Representatives with 119 votes (58 opposed). As a courtesy, the official copy of the resolution was sent to the White House for Lincoln’s approval, although that was not required by the Constitution; it remains the only constitutional amendment signed by a president. In this commemorative copy, a space was left open for President Lincoln in the center of the document, after “Approved February 1st 1865,” suggesting that signatures were still being gathered on this copy when Lincoln was shot on April 14, 1865. It sold at auction March 30, 2023.

Copycat $52,500 TOP

BID

COURTESY OF CIVIL WAR TRAILS INC.; SWANN GALLERIES

AMERICAN HISTORY 12 AMHP-230700-MOSAIC.indd 12 4/7/23 11:27 AM

You can’t always lie down in bed and sleep. Heartburn, cardiac problems, hip or back aches – and dozens of other ailments and worries. Those are the nights you’d give anything for a comfortable chair to sleep in: one that reclines to exactly the right degree, raises your feet and legs just where you want them, supports your head and shoulders properly, and operates at the touch of a button.

Our Perfect Sleep Chair® does all that and more. More than a chair or recliner, it’s designed to provide total comfort. Choose your preferred heat and massage settings, for hours of soothing relaxation. Reading or watching TV? Our chair’s recline technology allows you to pause the chair in an infinite number of settings. And best of all, it features a powerful lift mechanism that tilts the entire chair forward, making it easy to stand. You’ll love the other benefits, too. It helps with correct spinal alignment and promotes back pressure relief, to prevent back and muscle pain. The overstuffed, oversized biscuit style back and unique seat design will cradle you

OVER 100,000 SOLD

OVER 100,000 SOLD

in comfort. Generously filled, wide armrests provide enhanced arm support when sitting or reclining. It even has a battery backup in case of a power outage.

White glove delivery included in shipping charge. Professionals will deliver the chair to the exact spot in your home where you want it, unpack it, inspect it, test it, position it, and even carry the packaging away! You get your choice of Luxurious and Lasting Miralux, Genuine Leather, stain and liquid repellent Duralux with the classic leather look, or plush MicroLux microfiber, all handcrafted in a variety of colors to fit any decor. Call now!

1-888-866-6209

Please mention code

“To you, it’s the perfect lift chair. To me, it’s the best sleep chair I’ve ever had.”

— J. Fitzgerald, VA 3CHAIRS

IN ONE: SLEEP/RECLINE/LIFT

46642 Because

bedding product it cannot be returned, but if it arrives damaged or defective, at our option we will repair it or replace it. Delivery only available in contiguous U.S. © 2023 Journey Health and Lifestyle. ACCREDITED BUSINESS A+ enjoying life never gets old™ mobility | sleep | comfort | safety REMOTE-CONTROLLED EASILY SHIFTS FROM FLAT TO A STAND-ASSIST POSITION Now available in a variety of colors, fabrics and sizes.

each Perfect Sleep Chair is a made-to-order

MicroLux™ Microfiber breathable & amazingly soft New & Improved Long Lasting DuraLux™ stain & liquid repellent Genuine Leather classic beauty & style Chestnut AMHP-230516-009 Journey Health & Lifestyle Perfect Sleep Chair.indd 1 3/31/2023 2:31:18 PM

Pictured is Luxurious & Lasting Miralux™. Ask about our 5 Comfort Zone chair.

Picture Perfect

Ox teams provided a lot of draft power for farmers from the 17th century through the opening of the 20th century. They were particularly prevalent in New England and the Mid-Atlantic states. This proud drover poses with his team in the middle of a muddy street. The solid hue of the beasts might be a clue that they are Red Devons, one of the earliest ox breeds to be used in America. Note that a horse makes an appearance at lower right. And most curiously, two young men have photobombed the scene by posing in the act of having a bare-knuckle showdown.

ABT Marks Milestone Preservation Victory

After taking possession of 117 acres at Buffington Island, site of the largest Civil War battle in Ohio, the American Battlefield Trust has now protected hallowed ground at half the states in the Union. Founded in 1987 in Virginia, the Trust has saved a total of 56,000 acres across 155 sites in 25 states. Geographically, the organization’s footprint stretches from upstate New York westward to New Mexico, and chronologically from the “shot heard ’round the world” at Lexington and Concord that began the Revolutionary War to the stillness at Appomattox as the Civil War drew to a close.

The Trust first announced its intention to secure the Ohio site, adjacent to the existing Buffington Island Battlefield Memorial Park, in the spring of 2022 with assistance from the Buffington Island Battlefield Preservation Foundation.

In March, the Trust also announced the protection of a combined 47 acres at both the Cedar Creek Battlefield and the Cedar Mountain Battlefield.

The land was saved with the assistance of the National Park Service, American Battlefield Protection Program, Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation, Virginia Land Conservation Fund, and Trust donors.

The newly saved property at Cedar Creek is adjacent to park headquarters and on a central part of the battlefield, once touched by the determined actions of Union and Confederate troops on October 19, 1864, during the boldly executed Battle of Cedar Creek.

DANA B. SHOAF COLLECTION

AMERICAN HISTORY 14 AMHP-230700-MOSAIC.indd 14 4/7/23 11:27 AM

KnightMuseum& SandhillsCenter & SallowsMilitary Museum

ChartyourCoursetoexperiencetheunexpected discoveriesinandaroundAlliance,Nebraska wherethereishistoryateveryturn.Fromscenic drives,toourlocalbrewery,remarkableparks, richartandthelegendaryCarhenge;youwillbe transportedtoanostalgicplacewherequaint shopslineourhistoricdowntownbrickpaved streetsandfolksyou’venevermetwillsmileand wave.Ourhospitalityandbeautyofourcitywill leaveyouwantingtocomebackformore.

Planyourgetawaynowbyvisiting www.visitalliance.com

Veteran's Cemetery

Dobby's Frontier

DANA B. SHOAF COLLECTION

AMHP-230516-002 Alliance Tourism.indd 1 4/6/2023 12:34:09 PM AMHP-230700-MOSAIC.indd 15 4/7/23 11:28 AM

Outside the Box

Innovations

DESPITE ADVANCES in the comfort and usefulness of the catcher’s mitt by the early 1900s, one can assume that James E. Bennett III of Momence, Ill., was not a fan when, in 1904, he patented this “base ball catcher.” The contraption included a cage attached to the player’s chest, reinforced on all sides with wood and springs at the back to cushion the blow. Once

the ball passed through the open front end, it closed automatically, and the ball would drop out through a tube at the bottom. Seemingly designed to free up the catcher’s hands, Bennett’s device was never produced nor used in a game. You could say, it never caught on. —Melissa

A. Winn

AMERICAN HISTORY 16 NATIONAL ARCHIVES

AMHP-230700-INNOVATIONS.indd 16 4/6/23 11:22 AM

The Day the War Was Lost It might not be the one you think Security Breach Intercepts of U.S. radio chatter threatened lives 50 th ANNIVERSARY LINEBACKER II AMERICA’S LAST SHOT AT THE ENEMY First Woman to Die Tragic Death of CIA’s Barbara Robbins HOMEFRONT the Super Bowl era WINTER 2023 WINTER 2023 Vicksburg Chaos Former teacher tastes combat for the first time Elmer Ellsworth A fresh look at his shocking death Plus! Stalled at the Susquehanna Prelude to Gettysburg Gen. John Brown Gordon’s grand plans go up in flames MAY 2022 In 1775 the Continental Army needed weapons— and fast World War II’s Can-Do City Witness to the White War ARMS RACE THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF MILITARY HISTORY WINTER 2022 H H STOR .COM JUDGMENT COMES FOR THE BUTCHER OF BATAAN THE STAR BOXERS WHO FOUGHT A PROXY WAR BETWEEN AMERICA AND GERMANY PATTON’S EDGE THE MEN OF HIS 1ST RANGER BATTALION ENRAGED HIM UNTIL THEY SAVED THE DAY JUNE 2022 JULY 3, 1863: FIRSTHAND ACCOUNT OF CONFEDERATE ASSAULT ON CULP’S HILL H In one week, Robert E. Lee, with James Longstreet and Stonewall Jackson, drove the Army of the Potomac away from Richmond. H THE WAR’S LAST WIDOW TELLS HER STORY H LEE TAKES COMMAND CRUCIAL DECISIONS OF THE 1862 SEVEN DAYS CAMPAIGN 16 April 2021 Ending Slavery for Seafarers Pauli Murray’s Remarkable Life Final Photos of William McKinley An Artist’s Take on Jim Crow “He was more unfortunate than criminal,” George Washington wrote of Benedict Arnold’s co-conspirator. No MercyWashington’s tough call on convicted spy John André HISTORYNET.com February 2022 CHOOSE FROM NINE AWARD - WINNING TITLES Your print subscription includes access to 25,000+ stories on historynet.com—and more! Subscribe Now! HOUSE-9-SUBS AD-11.22.indd 1 12/21/22 9:34 AM

The Dark Side of the White Knight

by Peter Carlson

THE STOCK MARKET had been falling for a month, slowly at first, then faster. On Friday, October 18, 1929, the decline hastened in heavy trading. On Monday, prices fell again. On Tuesday, they rose a bit, only to plummet on Wednesday. On the morning of Thursday, October 24—the day dubbed “Black Thursday”—prices tumbled so fast that spectators in the gallery began to weep.

American Schemers

At 1:30 that afternoon, Richard Whitney, acting president of the New York Stock Exchange, appeared on the trading floor and strode briskly to Post Number 2, where stocks in U.S. Steel were traded. Tall and distinguished, Whitney stood silent for a moment, with a golden pig—the symbol of his Harvard dining club—dangling from the watch chain encircling his prosperous paunch. He had just convened a meeting of the nation’s most powerful bankers, who agreed to put up $20 million to stop the sell-off and stabilize prices. The room fell silent as traders strained to hear what Whitney would say.

He asked the price of U.S. Steel’s stock and was informed that it had fallen below $200 a share. “I bid 205 for 10,000 Steel,” he responded.

Then he moved to other posts and paid generous prices for other blue-chip stocks. It worked: the market rallied and Whitney became a hero. “Richard Whitney Halts Stock Panic,” read one headline, and tabloids dubbed him the “White Knight of Wall Street.”

The rally didn’t last long—the market crashed

BETTMANN/GETTY IMAGES BERT MORGAN/GETTY IMAGES

AMERICAN HISTORY 18

AMHP-230700-SCHEMERS.indd 18 4/6/23 11:19 AM

At the Height of His Power Richard Whitney, titan of the New York Stock Exchange, poses with his wife, Gertrude, at left, and his daughter, Nancy, in 1934.

five days later, leading to the Great Depression—but Whitney’s fame endured. He served five years as president of the New York Stock Exchange, and became a symbol of America’s old-money, blue-blood elite—first for his coolness in crisis, then for his arrogance and corruption.

He was born in Boston in 1888, to a family that had arrived in Massachusetts in 1630. His father was a bank president. His uncle and his brother were executives in J.P. Morgan’s financial empire. At Groton, Whitney was captain of the baseball team. At Harvard he rowed on the varsity crew. He married a rich woman and started his own brokerage firm—Richard Whitney & Co.—which, thanks to his connections, became the official broker for the House of Morgan. He bought a five-story townhouse on East 73rd Street in Manhattan and a 495-acre estate in New Jersey, where he raised thoroughbred horses and served as Master of Fox Hounds for the Essex Hunt.

As president of the Stock Exchange during the early 1930s, Whitney found himself battling another graduate of both Groton and Harvard—President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. When FDR backed a bill to create the Securities and Exchange Commission to regulate the stock market, Whitney led the battle against it. The regulations were a “menace to national recovery,” he said, and if they were adopted, “grass will grow on Wall Street.” There’s no need for government regulation, he insisted: “The exchange is a perfect institution.”

Whitney ’s lobbying failed to convince Congress, which passed the bill creating the S.E.C. Then Roosevelt appointed Joseph P. Kennedy—a savvy former stock manipulator himself—as S.E.C chairman, reasoning that Kennedy knew all the dirty tricks of the trade and could therefore crack down on them.

Whitney detested Kennedy as a traitor to the exchange but he admired Kennedy’s financial wizardry. When Prohibition was repealed in 1933, Kennedy made a fortune importing Haig & Haig Scotch and Gordon’s Gin. Inspired, Whitney decided to get into the booze business. He founded the Distilled Liquors Corporation and began producing an applejack called Jersey Lightning. It failed to catch on. He imported 106,000 gallons of Canadian rye whiskey, but that didn’t sell either. When Distilled Liquors’ stock plummeted, Whitney tried to boost the price by borrowing millions to buy more shares. It didn’t work. Apparently, nobody wanted his booze or his stock. Desperate, Whitney borrowed more money from his wealthy friends to finance various get-rich-quick schemes. But they, too, failed.

So “the White Knight of Wall Street,” started stealing.

Whitney’s first theft was $150,200 in bonds belonging to the New York Yacht Club, for which he served as treasurer. But that wasn’t enough to save his crumbling empire, so he stole from his brokerage firm’s customers— Harvard University, St Paul’s School, his father-in-law’s estate, his wife’s trust fund. And he embezzled more than $1 million from the New York Stock Exchange’s Gratuity Fund. That fund paid benefits to the families of deceased members of the Exchange, so Whitney’s theft, wrote Wall Street historian John Steele Gordon, “amounted, almost literally, to stealing from widows and orphans.”

Inevitably, Whitney’s schemes collapsed. Rumors spread on the street that his company was failing. Officials of the exchange investigated and discovered that Whitney was embezzling from his customers. Undaunted and arrogant, Whitney tried to convince Charles Gay, his successor as president of the exchange, to cover up his crimes.

“I am Richard Whitney,” he told Gay. “I mean the stock exchange to millions of people. The exchange can’t afford to let me go under.”

In Whitney ’s heyday, the exchange’s old-boy network might have protected him. But, as Gay understood, in the new era of S.E.C watchdogs, that was no longer an option. So, on the morning of May 7, 1938, Gay announced

to the exchange that Whitney and his company were suspended for “conduct contrary to just and equitable principles of trade.”

“Not Dick Whitney!” President Roosevelt said when aides told him the shocking news about his fellow Groton grad. “Dick Whitney—I can’t believe it.”

“Wall Street could hardly have been more embarrassed,” The Nation magazine noted, “if J.P. Morgan had been caught helping himself from the collection plate at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.”

Indicted for fraud and embezzlement, Whitney pled guilty and was sentenced to 5–10 years in prison. The next day, a crowd packed Grand Central Station to gawk as cops loaded five handcuffed prisoners onto a train bound for Sing Sing Prison—a rapist, two extortionists, a holdup man, and the former president of the New York Stock Exchange.

Whitney served three years and four months before he was paroled in 1941. Barred from the securities business, he managed a family-owned dairy farm in Massachusetts. His wife took him back and his brother repaid every dollar Whitney had stolen.

When he died in 1974, at age 86, his obituary in The New York Times noted the irony that Whitney’s shocking scandal had led to the enactment of the regulations he had fought so hard against: “It hastened the adoption of drastic reforms governing stock market dealings, long pressed by the Securities and Exchange Commission and resisted by an old-guard clique on the Street whose powerful leader had been Mr. Whitney himself.” H

BETTMANN/GETTY IMAGES BERT MORGAN/GETTY IMAGES SUMMER 2023 19

AMHP-230700-SCHEMERS.indd 19 4/6/23 11:19 AM

Leaving the Big House Whitney walks out of New York’s Sing Sing Prison in 1941. His final career was managing dairy cows instead of capital.

Number Two

by Richard Brookhiser

POOR KAMALA HARRIS. The vice president took office in January 2021 trailing a cloud of firsts: first woman to hold the job, first African American (thanks to her Jamaican father), first Asian-American (thanks to her Indian mother). But the job itself has been a cavalcade of vexations. President Joe Biden saddled her with an unattractive assignment—managing and explaining the migrant mess at the southern border. She is reputed to be hard on her staff in private, and she is often tongue-tied in public. Even media outlets friendly to the administration have run hit pieces on her.

According to The New York Times, “dozens of Democrats in the White House, on Capitol Hill, and around the nation” said (anonymously) that “she had not risen to the challenge of proving herself as a future leader of the party, much less the country.”

The office of vice president was devised in the home stretch of the Constitutional Convention as a flywheel in the machinery for picking an executive, and a successor in case the president died or was removed from office. Along the way, Elbridge Gerry worried that veeps would be too closely allied to the presidents alongside whom they served, which provoked a snort from Gouverneur Morris: “the vice president will then be the first heir apparent that ever loved his father.” Initially the vice

presidency went to the runner-up in the Electoral College’s vote for president; the 12th amendment (1804) ensured that the veep would be the running mate of the winning presidential candidate.

The office got off to a rough start. John Adams, first vice president under George Washington, was the first (though not the last) to feel that he had nothing to do. Thomas Jefferson, second vice president under Adams, spent his term undermining his old friend and plotting to supplant him. Aaron Burr, third vice president under Jefferson, was shut out of all patronage, denied renomination when Jefferson ran again, and spent his post–vice presidential years plotting to break up the United States.

Most modern vice presidents, beginning with Walter Mondale, Jimmy Carter’s number two, have been given substantive responsibilities, and have worked well with their number ones. Four of them—Mondale, George H.W. Bush, Al Gore, Joe

BETTMANN/GETTY

IMAGES

AMERICAN HISTORY 20

Déjà Vu

Guess Who?

AMHP-230700-DEJAVU.indd 20 4/10/23 9:58 AM

You all know the man to the left, but who is that man at right? Why it’s FDR’s 2nd vice president, Henry Agard Wallace, who served from 1941-1945.

Hunting is our heritage, our heart, and our future.

Hunting is our heritage, our heart and our future.

A DEFINITIVE STUDY OF THE MIND, BODY, AND ECOLOGY OF THE HUNTER IN THE MODERN WORLD

Where does hunting fit in the modern world? To many, it can seem outdated or even cruel, but as On Hunting affirms, hunting is holistic, honest, and continually relevant. Authors Lt. Col. Dave Grossman, Linda K. Miller, and Capt. Keith A. Cunningham dive deep into the ancient past of hunting and examine its position today, demonstrating that we cannot understand humanity without first understanding hunting.

Readers will…

• discover how hunting formed us,

• examine hunting ethics and their adaptation to modernity,

• understand the challenges, traditions, and reverence of today’s hunter,

• identify hunting skills and their many applications outside the field,

• learn why hunting is critical to ecological restoration and preservation, and

• gain inspiration to share hunting with others.

Drawing from ecology, philosophy, and anthropology and sprinkled with campfire stories, this wide-ranging examination has rich depths for both nonhunters and hunters alike.

On Hunting shows that we need hunting still—and so does the wild earth we inhabit.

“All true hunters ‘feel’ the truth, but few are able to ‘articulate’ that truth. Now, thankfully, we have On Hunting to be our champion of the wild!”

Order your copy today at GrossmanOnTruth.com AMHP-230516-010 Grossman on Truth Book.indd 1 3/28/23 2:10 PM

—JIM SHOCKEY, Naturalist, Outfitter, TV Producer and Host

Biden—have run for president themselves, two— Bush and Biden—successfully. But two vice presidents of an earlier era anticipated the problems bedeviling Harris today.

Henry Wallace was the scion of an Iowa family of farmer/journalists (they published a magazine called Wallace’s Farmer). His father served as secretary of Agriculture under Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge; Henry, crossing party lines, held the same job for FDR. In addition to his interests in crop cycles and new plant strains, Wallace had a passion for oddball religions. In the 1920s he came under the spell of Nicholas Roerich, a Russian émigré painter and seer who dressed in Tibetan robes and claimed to be the reincarnation of a Chinese emperor. Wallace and Roerich exchanged hundreds of letters, in which they referred to each other and to famous acquaintances in mystical code: Roerich was the Guru, Wallace was Parsifal or Galahad, FDR was the Flaming One, or the Wavering One, whenever Wallace felt disappointed in him.

In 1934 Wallace got Roerich attached to an Agriculture Department expedition to Mongolia seeking drought-resistant grasses. Roerich was also seeking the Holy Grail on the side. American diplomats reported that he was traveling the steppes with a bodyguard of White Russian Cossacks, trying to set up a Central Asian Buddhist kingdom. Wallace, embarrassed, cut ties with him.

The Flaming One, tired of his crusty Texan veep John Nance Garner, tapped Wallace to be his running mate when he sought a third term in 1940. FDR wanted a man of liberal views, and Wallace fit the bill. One potential landmine threatened the new ticket. The Republican National Committee had procured copies of 120 Guru letters. The GOP

candidate Wendell Willkie nixed using them, however, afraid that the Democrats would expose his long-running extramarital affair with a prominent New York journalist. Roosevelt and Wallace cruised to victory.

Wallace found new soul mates post-Roerich—American Communists, whose designs he naively failed to penetrate. The Soviet Union was a wartime ally, and Communists were billing themselves as liberals in a hurry. Alarmed Democratic bosses told FDR in 1944 that he must dump Wallace, so the nod for his fourth run went to Missouri Senator Harry Truman, who became president when Roosevelt died three months into his last term. When Wallace ran for president himself in 1948 as candidate of the left-wing Progressive Party, the Guru letters finally hit the papers. Wallace won a meager 2.4 percent of the popular vote, and carried no states. Repenting of his pro-Soviet backers, he lived until 1965.

Richard Nixon was tied to Dwight Eisenhower politically and personally. He served as Eisenhower’s veep for two terms, 1953–1961. After Nixon won the White House himself in 1968, his daughter Julie married Ike’s grandson, David Eisenhower. Yet his relationship with Ike was always fraught.

Nixon had been put on the ticket in 1952 as a sop to the conservative wing of the GOP that Ike had defeated in winning the nomination. The two barely knew each other, however. There was a 23-year age gap between them. In September, the press revealed that Nixon had a campaign expense account, characterized in headlines as SECRET RICH MEN’S TRUST FUND. Ike’s advisers, fearful of any taint on the war-winning hero, pressured Nixon to resign from the ticket. Instead he made a half-hour television speech, defending his innocence (the account was legal), attacking Democrats (Ike’s rival, Adlai Stevenson, had his own campaign account), and pledging to keep Checkers, a cocker spaniel that a supporter had given Nixon’s daughters. The Republican National Committee got millions of letters, telegrams, and phone calls praising the put-upon Nixon. Ike embraced his feisty running mate.

But their relations never warmed. Nixon was intelligent and hard-working, but too political and ambitious for his old boss. In August 1960, at the end of Eisenhower’s second term and the start of Nixon’s first presidential run, against Sen. John F. Kennedy, the president was asked at a press conference what role Nixon had played in his administration. Had the vice president offered any “major idea” that Ike had subsequently adopted? “If you give me a week,” Eisenhower answered, “I might think of one. I don’t remember.” The Kennedy campaign gleefully used the line in an attack ad. Had Ike meant it as a flat-out diss? Probably not. But he hadn’t made a ringing endorsement either. The 1960 race was razor thin. Could a love-bombing Eisenhower have pulled Nixon over the line? Nixon would have to wait eight more years for a second shot.

The Vice President is a constitutional fixture and a political anomaly—a high official with hardly any defined role; a successor whom the president picks but cannot fire until and unless he runs again. Wallace was a deficient veep whom the president—and almost only the president—liked. Nixon was a work horse the president never truly admired. Kamala Harris seems to enjoy the worst of both worlds: low achievement, low esteem. With Biden determined to run again, will she be replaced a la Wallace, or retained a la Nixon? All the political termites of D.C. will be gnawing on that question. H

IRVING HABERMAN/IH IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES

AMERICAN HISTORY 22

Stepping Out on His Own Henry Wallace campaigns as president in Philadelphia in 1948. He ran as a candidate of the left-wing Progressive Party.

the AMHP-230700-DEJAVU.indd 22 4/10/23 9:58 AM

Democratic bosses told FDR in 1944 that he must dump Wallace, so the nod for his fourth run went to Missouri senator Harry Truman.

Gina Elise’s

PIN-UPS FOR VETS

Pin-Ups For Vets raises funds to better the lives and boost morale for the entire military community! When you make a purchase at our online store or make a donation, you’ll contribute to Veterans’ healthcare, helping provide VA hospitals across the U.S. with funds for medical equipment and programs. We support volunteerism at VA hospitals, including personal bedside visits to deliver gifts, and we provide makeovers and new clothing for military wives and female Veterans. All that plus we send care packages to our deployed troops.

visit: pinupsforvets.com

IRVING HABERMAN/IH IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES

Alicia, Army Veteran

Supporting Hospitalized Veterans & Deployed Troops Since 2006 AMHP-230700-DEJAVU.indd 23 4/10/23 9:58 AM

The History of History

In addition to stunning exhibit galleries, the DAR museum has 30 period rooms that have interesting history in their own right. The Colonial Revival kitchen was created in 1930 and sponsored by Oklahoma.

What Does Home Mean?

Historic furnishings and objects explore the country’s diverse living experiences

Interview by Melissa A. Winn

THE DAUGHTERS of the American Revolution Museum in Washington, D.C., houses an impressive collection of nearly 30,000 objects made and used prior to the Industrial Revolution. As the museum’s director and chief curator, Heidi Campbell-Shoaf oversees the museum staff, works with the National DAR organization that serves as the museum’s executive board and helps curate the collections that the museum exhibits in accordance with its current mission statement.

“We want to use the lens of the different interpretations of home,” she says, “to inspire conversations about the American experience and encourage people to discover commonalities between different American life experiences.”

What is the history of the DAR Museum?

The museum was founded in 1890, at the same time the national organization of the Daughters of the American Revolution was crafted. The museum’s intent was to collect and preserve historical artifacts, many of which were donated by DAR members. The DAR is a lineage organization which requires a woman to have a direct descent from somebody who aided the American Revolution. Soon after the museum was founded, the collection shifted to focus less on artifacts that people

would assume to be related to the Revolution— namely military items such as muskets, swords, powder horns, and uniforms—to objects that the Revolutionary generation had in their homes. From that point on, it has been a museum that collects and preserves and interprets objects used in American homes of the past.

Can you tell us about the history of the period rooms?

Some of them date all the way back to the initial building of the DAR Headquarters and Museum in Memorial Continental Hall in 1910. As the headquarters, Memorial Continental Hall was built with a lot of offices in the building. The DAR is organized very similar to our government, with a central executive, state organizations, and within those state organizations, local chapters. The state organizations donated money to help build Memorial Continental Hall and in return secured the right to put the state name on an

COURTESY OF HEIDI CAMPBELL-SHOAF OKLAHOMA SOCIETY DAUGHTERS OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

AMERICAN HISTORY 24

AMHP-230700-INTERVIEW.indd 24 4/6/23 11:12 AM

office room. The period rooms today still have state affiliations because they started as the state sponsored office space. When the organization outgrew the first building and built an addition and moved offices there, those rooms became the period rooms, and the states would furnish them as historic interiors. In the late 1930s, all of the period rooms were moved under the control of the museum, and it’s been that way ever since. The museum maintains the rooms and interprets historic interiors from the 1600s through the 1930s in them. They’re furnished as bedrooms, dining rooms, living rooms, parlors, etc. Most museums have somewhere between 5 and 10 percent of their collections on display, but we have well beyond that because of the period rooms

What do the gallery exhibits focus on?

The exhibits have a wide range of topics. Our curators have specialties to the collection they manage, care for, and develop, and they conduct original research and put together exhibitions. The topics are in part pulled from the curator’s expertise or research interest. But they all have some relationship to the American home. Our current exhibition is about portraiture and power in the American home and looking at these portraits that many of us see in museums. They are by and large painted for people to hang in their homes, so what does that say about the people who have the portrait painted, the people painting the portraits, the people seeing the portraits in the homes? What is that statement being made? It all circles back to the home in some way.

When you purchase something for the museum, how are you looking to expand the collections?

Each of our curators look at their collections, and have a statement of collecting for each different category. For example, fine art, glass, ceramics, etc. We look at the mission and we look at the collections and we say, ‘Do we have everything we need to tell particular stories?’ Of course, much of our collection has been donated to us over the years by DAR members. So that reflects much of the demographic of the DAR membership, which in the past, up until the 1970s, was primarily White, middle and upper class. The membership is becoming much more diverse, and we want to make sure that our collections reflect that and that we are not just interpreting the DAR homes of the past, but a broader interpretation of American homes. It’s all American homes. Not just those related to the American Revolution. That means we need to look at the collections and see where we have gaps in representation. For instance, a few years ago we purchased a sampler from

California that was made by somebody of Mexican ancestry, and of course, early California was Mexico. We have purchased objects made by native Hawaiians. We’ve acquired objects made by African American people or that portray the picture of African American people. We look at what’s missing and we also look at what we have and determine whether it’s the best example of the object we can display. Is it displayable? Then we may decide we need to have a better example of something we already have.

What’s a favorite object of yours in the collection?

That’s a tough question! What’s amazing about the DAR Museum collections in general is that there are so many of the objects that have stories associated with them—family history, historic events at which this object was present. And many of the objects are amazing examples of historic craftsmanship. So, that’s a hard question. I could pick many things for different reasons. One example, there’s a painting in our current exhibition, it’s on the cover of our current exhibition catalog. She’s dressed in clothing from the 1810s. She’s holding a green parrot. It’s a fabulous painting I think, for a lot of different reasons. It’s well done. But, also, why do you choose to be painted with a parrot in your hand? You can tell she has money, because why else would she have a parrot? Dolley Madison had a parrot. The average person is not going to have a parrot. She also wears a tiara with gold and coral. The colors are fabulous.

America will be celebrating its 250th anniversary in 2026. What is the museum planning for its celebration? We are planning programming as we get closer to the 250th. We are also planning an exhibition. People may be surprised to find out that we don’t have a lot of Revolutionary War–related objects in the collection. Because of the ongoing emphasis on objects that are found in the home, they aren’t by and large militaria. We’re looking at an exhibition focused on people who were writing about the Revolution, prior to the Revolution, and through the Revolution. We’re using some of the collection housed in the DAR Americana Collection, which is a collection of historic manuscripts and documents. We’re working to combine some of that collection with some three-dimensional items from the museum collection to create that exhibition. Leading up to that, we have an exhibition in 2025 that focuses on Black craftspeople and their fight for freedom and liberty and what that means for them, not just in the Revolutionary period but all the way through the 19th century, as well.

A Decade of Service

Heidi Campbell-Shoaf has been with the DAR Museum since 2013. She oversaw the construction of two new exhibit galleries in 2017.

Do you find that visitors have different expectations of what the museum will hold or the stories it will tell?

I think so, yes. When people come to a museum like ours, they often want to find confirmation of their own interpretation of history. Sometimes they find that and sometimes they don’t. And when they don’t, that’s when education happens. We do have people who come with perceptions of what the DAR is as an organization, which has evolved since the one incident that people remember—in 1939 Marian Anderson was denied an opportunity to perform at the DAR Constitution Hall because of her race. That perception has stuck in people’s mind for decades, so they think they know what they will find when they come to the museum, but I think some of them are pleasantly surprised that we provide a wide lens onto American history. H

COURTESY OF HEIDI CAMPBELL-SHOAF OKLAHOMA SOCIETY DAUGHTERS OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION SUMMER 2023 25

AMHP-230700-INTERVIEW.indd 25 4/6/23 11:12 AM

Present and Past

The Drake Well Museum and Park boasts a full-size replica of Edwin Drake’s worldchanging well, 240 acres to wander, and a large collection of rare early oil-drilling artifacts. The surveyors in the 1860s image at left undoubtedly came to Titusville to lay out their fortune.

JIM WEST/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; DANA B. SHOAF COLLECTION; THIS PAGE: RBM VINTAGE IMAGES/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO AMERICAN HISTORY 26 AMHP-230700-AMERICAN-PLACE.indd 26 4/6/23 11:09 AM

Edwin Drake’s Well

PEOPLE LIVING NEAR TITUSVILLE, PA., had long been aware of the gooey substance seeping out of the ground. For thousands of years, the black ooze was used for medicinal purposes. Small doses were used to treat scabies, respiratory illnesses, and even epilepsy. The native Seneca people, on whose land present-day Oil City is located, used it for ointments and insect repellant. But it also fouled the water. No one realized this rural section of northwestern Pennsylvania would become the cradle of the modern petroleum oil age.

American Place

By the 1850s, scientists and entrepreneurs knew that the substance had a potential to replace the whale oil that lit homes across the country and to lubricate the engines of the booming Industrial Revolution. The problem was getting the oil out of the ground fast enough and at enough quantity to make it worth while. Enter Edwin Drake, a former New York railroad worker hired by the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company of New York to attempt to drill for oil on a plot of land along Oil Creek, near Titusville, in 1857. Drake had no background in geology or drilling and it appears his job for the oil company was due to having invested $200—his life savings—in the company and having a railroad pass.

Drake hired William Smith, a blacksmith who had some experience working on salt wells, as his driller. A way to get to salt deposits without shaft mining, salt wells involved drilling down to a deposit, flooding it with water, and pumping the saline solution to the surface to evaporate. Even with Smith’s expertise, water from Oil Creek kept filling up the well. Finally, in early August 1859, Drake and Smith developed the “drive pipe” method of drilling, which inserted a cast iron pipe down the well to protect the drill and keep water at bay. Drilling three feet a day, they struck oil at the depth of 69.5 feet on August 27, 1859.

Soon after, despite a civil war, people flooded into Titusville, a ham let of 250 people. By 1865, the population had grown to 10,000. That same year, a new town with the illustrious name of Pithole City was founded near another well. In just six months, Pithole City boasted 16,000 peo ple, dozens of hotels, banks, stores, and saloons, and a daily mail delivery of more than 6,000 letters. Unreliable oil markets, fires, and decreasing oil production led to Pithole’s demise, just as quickly as it appeared. By 1877, it was a ghost town.

“Oil Fever” still burned in Western Pennsylvania, though it was much tempered after the early decades. Focus turned to refining the oil the wells brought to the surface, producing kerosene for the new lamps in people’s homes. In 1901, oil was found in Texas and all eyes shifted to the Lone Star State, where Pennsylvania drills and refining equipment supplied a new oil boom.

—Heidi Campbell-Shoaf

—Heidi Campbell-Shoaf

Population Boom

Oil well and storage tanks climb the heights from Oil Creek near Titusville, Pa. One area well, McClintock

Well #1, still pumps oil. The PHMC owns the well and uses its proceeds to keep up their historic properties.

Derricks and Ghost Towns

H Drake Well Museum and Park, 202 Museum Lane, Titusville, Pa., is home to a reproduction of Drake’s well house over the original well. Administered by the Pennsylvania History and Museum Commission (PHMC), it offers indoor and outdoor exhibits and programs both at the well and at the Pithole City ghost town.

H Western Pennsylvania is well-known for its football history. Johann Wilhelm Heisman, son of German immigrants, was raised in Titusville. In high school,

ark Road, Oil City, Pa.

OH NY DRAKE WELL MUSEUM PITTSBURGH LAKE ERIE PA SUMMER 2023 27 JIM WEST/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; DANA B. SHOAF COLLECTION; THIS PAGE: RBM VINTAGE IMAGES/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO AMHP-230700-AMERICAN-PLACE.indd 27 4/6/23 11:09 AM

TODAY IN HISTORY

MAY 6, 1996

FORMER DIRECTOR OF THE CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY WILLIAM COLBY IS FOUND DEAD ON A RIVERBANK IN ROCK POINT, MD. AN AVID OUTDOORSMAN, HE HAD SET OUT ON A SOLO CANOE TRIP NINE DAYS EARLIER. CONSPIRACY THEORIES ABOUND REGARDING THE CAUSE OF HIS DEATH. CLOAK AND DAGGER DAYS BEHIND HIM, COLBY WAS QUOTED AS SAYING “THE COLD WAR IS OVER, AND THE MILITARY THREAT IS NOW FAR LESS, IT’S TIME TO CUT OUR MILITARY BUDGET BY 50 PERCENT AND TO INVEST THAT MONEY IN OUR SCHOOLS, OUR HEALTH CARE, AND OUR ECONOMY.”

For more, visit HISTORYNET.COM/ TODAY-IN-HISTORY

TODAY-COLBY.indd 22 3/31/23 8:43 AM

Connecting Routes

by Dana B. Shoaf

CONGRESS

Commerce!

Lots going on in this 1890 image of the Erie Canal at Little Falls, N.Y. An unusual canal warehouse dominates the scene, and several people, including a woman, stand on the canal boats. Families would live on the boats for months at a time. A West Shore Railroad train puffs in from the left.

Editorial

HISTORICAL CONNECTIONS have a stealth factor. Take this issue. We planned no theme for it, we really never do. The goals is diversity in content. But...a bit of a theme emerged by accident. “Terra Firma” takes a look at an Erie Canal map, (P. 62). That busy ditch provided immigrants a fast and reliable transportation route from the East Coast to the Midwest. A number of 48er revolutionaries (P. 54) and other Germans fled oppression overseas and came to New York City, then made their way along the canal en route eventually to cities such as Chicago and Milwaukee. During the birth of the new political party system in the mid-19th century, many of them joined the Republican Party and would eventually cast their ballots for that gangly Illinois lawyer who kept a scrapbook (P. 30). Some would even die under his leadership, fighting for the Union Army. The themes of history can sneak up on you.

LIBRARY OF

SUMMER 2023 29

AMHP-230700-EDITORIAL.indd 29 4/10/23 11:16 AM

PHOTO CREDIT AMHP-230700-LINCOLN.indd 30 4/6/23 10:57 AM

Lincoln in His Own Words

The 16th president’s pre-Civil War musings about ‘negro equality’

By Ross E. Heller

Prairie Lawyer

Artist George A.P. Healy painted this portrait of Abraham Lincoln from life in 1860. It took three sittings to complete the artwork. An intense study of the painting revealed Healy slightly shifted Lincoln’s cheek to make his jaw less blocky.

PHOTO CREDIT

SUMMER 2023 31 AMHP-230700-LINCOLN.indd 31 4/6/23 10:57 AM

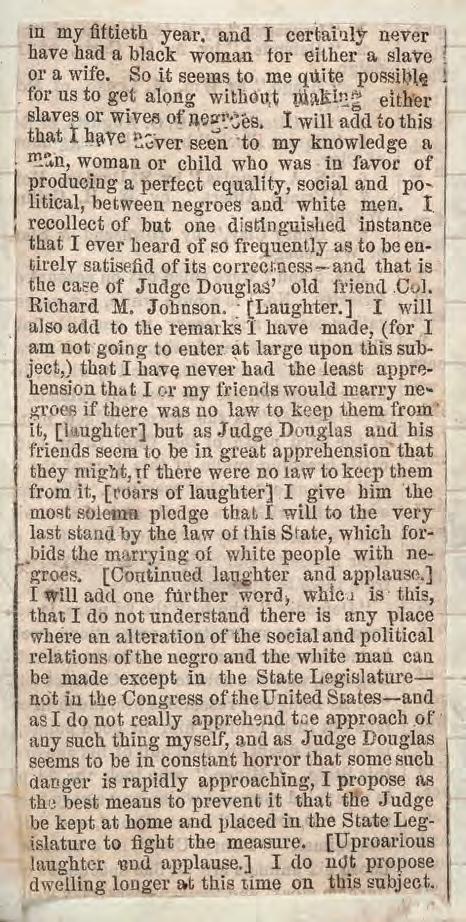

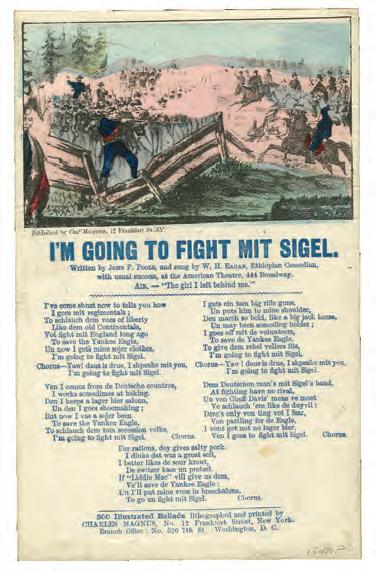

In 1858, Abraham Lincoln casually and unknowingly created a time capsule of his contemporary mindset on both slavery and race relations—not hidden in a cornerstone but taking the form of a 3.25by 5.78-inch black campaign notebook shared with Capt. James N. Brown, a longtime friend and fellow campaigner.

It was the waning days of Lincoln’s senatorial campaign against Stephen A. Douglas and Brown was running for Illinois state legislature, partly at Lincoln’s encouragement. Brown, however, was assailed for his ties to Lincoln. Virulent opponents said that Lincoln—and therefore Brown, by association—supported and wanted to bring about social and political Negro equality

Brown beseeched Lincoln for a clear statement on that Negro equality, what Brown referred to as the “paramount issue” of the day. Lincoln acceded, annotating what he called a “scrapbook” with news clips of his speeches on the subject, and a definitive 8-page letter, transcribed here.

Springfield, Oct. 18, 1858

Hon. J. N. Brown

My dear Sir

I do not perceive how I can express myself, more plainly, than I have done in the foregoing extracts. In four of them I have expressly disclaimed all intention to bring about social and political equality between the white and black races, and, in all the rest, I have done the same thing by clear implication

I have made it equally plain that I think the negro is included in the word “men’’ used in the Declaration of Independence.

I believe the declaration that “all men are created equal’’ is the great fundamental principle upon which our free institutions rest; that negro slavery is violative of that principle; but that, by our frame of government, that principle has not been made one of legal obligation; that by our frame of government, the States which have slavery are to retain it, or surrender it at their own pleasure; and that all others—individuals, free-states and national government—are constitutionally bound to leave them alone about it_

I believe our government was thus framed because of the necessity springing from the actual presence of slavery, when it was framed.

That such necessity does not exist in the territories, where slavery is not present_

In his Mendenhall speech Mr. Clay says “Now, as an abstract principle, there is no doubt of the truth of that declaration (all men created equal) and it is desirable, in the original construction of society, and in organized societies, to keep it in view, as a great fundamental principle’’

Again, in the same speech Mr. Clay says:

“If a state of nature existed, and we were about to lay the foundations of society, no man would be more strongly opposed than I should to incorporate the institution of slavery among its elements;”

Exactly so—In our new free territories, a state of nature does exist In them Congress lays the foundations of society; and, in laying those foundations, I say, with Mr. Clay, it is desirable that the declaration of the equality of all men shall be kept in view, as a great fundamental principle; and that Congress, which lays the foundations of society, should, like Mr. Clay, be strongly opposed to the incorporation of slavery among its elements_

But it does not follow that social and political equality between whites and blacks, must be incorporated, because slavery must not—

The declaration does not so require_

Yours as ever

A. Lincoln

AMERICAN HISTORY 32

PREVIOUS SPREAD: NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART; THIS PAGE AND OPPOSITE PAGE: ABRAHAM LINCOLN, HIS BOOK: A FACSIMILE REPRODUCTION OF THE ORIGINAL (5)

AMHP-230700-LINCOLN.indd 32 4/6/23 10:58 AM

Capt. James N. Brown

PREVIOUS SPREAD: NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART; THIS PAGE AND OPPOSITE PAGE: ABRAHAM LINCOLN, HIS BOOK: A FACSIMILE REPRODUCTION OF THE ORIGINAL (5) SUMMER 2023 33 AMHP-230700-LINCOLN.indd 33 4/6/23 10:58 AM

“...the spread of slavery, I can not but hate. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world— enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites....”

The Great Debates Lincoln gained great fame for his deft verbal jousting with Stephen Douglas in their 1858 Illinois debates.

Brown used the notebook from Lincoln during his campaign’s waning days. It didn’t help. He lost the election.

The scrapbook was cherished by Brown and, after his 1868 death, by his sons William and Benjamin. Eventually they sold it to New York rare-book dealer George D. Smith, who found a customer in Philadelphia Lincoln collector William H. Lambert, who believed Lincoln’s words warranted wider distribution and published a version of the notebook in 1901 as Abraham Lincoln: His Book: A Facsimile Reproduction of the Original with an Explanatory Note by J. McCan Davis.

After Lambert’s death the ‘scrapbook’ was auctioned in 1914; and purchased for Henry E. Huntington’s San Marino, California library. H

In his career Ross E. Heller, holder of a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Oregon, has been a journalist, U.S. Senatorial press secretary, lobbyist, association executive, entrepreneur, newspaper publisher and now, editor/author. Researching this book, he is also discoverer of new facts of America’s most-storied life; a life about which no one could imagine anything new could ever be found.

AMERICAN HISTORY 34 TOP: CLASSIC STOCK/GETTY IMAGES; ALL SCRAPBOOK EXCERPTS: ABRAHAM LINCOLN, HIS BOOK: A FACSIMILE REPRODUCTION OF THE ORIGINAL (10)

from By Abraham Lincoln: His 1858 Time Capsule, edited by Ross E. Heller and published by CustomNEWS, Seaside Books.

AMHP-230700-LINCOLN.indd 34 4/6/23 10:58 AM

TOP: CLASSIC STOCK/GETTY IMAGES; ALL SCRAPBOOK EXCERPTS: ABRAHAM LINCOLN, HIS BOOK: A FACSIMILE REPRODUCTION OF THE ORIGINAL (10)

SUMMER 2023 35 AMHP-230700-LINCOLN.indd 35 4/6/23 10:59 AM

“...I protest, now and forever, against that counterfeit logic which presumes that because I do not want a negro woman for a slave, I do necessarily want her for a wife. [Laughter and cheers.] ”