‘A fighting man, through and through, but wary and wily as brave.’

The charmed and cursed life of the war’s most famous boy general Federal Cavalry Comes of Age Battle Scars of Philippi, W.Va. Civilians Make Their Mark Plus!

Custer!

HISTORYNET.COM SUMMER 2023 ACWP-230700-COVER-DIGITAL.indd 1 3/13/23 2:19 PM

–Col. James H. Kidd

Personalized 6-in-1 Pen

Convenient “micro-mini toolbox” contains ruler, pen, level, stylus, plus flat and Phillips screwdrivers. Giftable box included. Aluminum; 6"L. 817970 $29.99

Mats

Grease Monkey or Toolman, your guy (or gal) will love this practical way to identify personal space. 23x57"W.

Tools 808724

Tires 816756 $45.99 each

Personalized Super Sturdy Hammer Hammers have a way of walking o . Here’s one they can call their own. Hickory-wood handle. 16 oz., 13"L. 816350 $21.99

Personalized Extendable Flashlight Tool

Light tight dark spaces; pick up metal objects. Magnetic 6¾" LED flashlight extends to 22"L; bends to direct light. With 4 LR44 batteries. 817098 $32.99

OFFER

Personalized Garage

ACWP-230418-006 Lillian Vernon .indd 1 3/14/23 4:55 PM

RUGGED ACCESSORIES FOR THE NEVER-ENOUGH-GADGETS GUY. JUST INITIAL HERE.

Our durable Lillian Vernon products are built to last. Each is crafted using the best materials and manufacturing methods. Best of all, we’ll personalize them with your good name or monogram. Ordering is easy. Shipping is free.* Go to LillianVernon.com or call 1-800-545-5426.

Personalized Grooming Kit

Indispensable zippered manmade-leather case contains comb, nail tools, mirror, lint brush, shaver, toothbrush, bottle opener. Lined; 5½x7".

817548 $29.99

Personalized Beer Caddy Cooler Tote Soft-sided, waxed-cotton canvas cooler tote with removable divider includes an integrated opener, adjustable shoulder strap, and secures 6 bottles. 9x5½x6¾". 817006 $64.99

Personalized Bottle Opener Handsome tool helps top o a long day with a cool brew. 1½x7"W. Brewery 817820 Initial Family Name 817822 $11.99 each

Personalized 13-in-1 Multi-Function Tool

All the essential tools he needs to tackle any job. Includes bottle opener, flathead screwdriver, Phillips screwdriver, key ring, scissors, LED light, corkscrew, saw, knife, can opener, nail file, nail cleaner and needle. Includes LR621 batteries. Stainless steel.

818456 $29.99

*FREE SHIPPING ON ORDERS OVER $50. USE PROMO CODE: HISACWM3 LILLIANVERNON.COM/ACW The Personalization Experts Since 1951 OFFER EXPIRES 7/31/23. ONLY ONE PROMO CODE PER ORDER. OFFERS CANNOT BE COMBINED. OFFER APPLIES TO STANDARD SHIPPING ONLY. ALL ORDERS ARE ASSESSED A CARE & PACKAGING FEE.

ACWP-230418-006 Lillian Vernon RHP.indd 1 3/14/23 4:59 PM

22 Summer of Discontent

George Armstrong Custer knew mostly glory in the war. That wouldn’t be the case during his late-war excursion to Louisiana.

By Richard H. Holloway

By Richard H. Holloway

2 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR CLOCKWISE FROM LEFT: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS; NIDAY PICTURE LIBRARY, LEBRECHT MUSIC & ARTS/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO (2); COVER: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY BRIAN WALKER

Summer 2023

ACWP-230700-CONTENTS.indd 2 3/15/23 8:55 AM

The Reckoning at Yellow Tavern

By Adolfo Ovies

By Adolfo Ovies

Home

SUMMER 2023 3

6 LETTERS In Ben Butler’s own words 8 G RAPESHOT! Britain’s Civil War heroes remembered; history at Ball’s Bluff 12 REGIMENTAL PRIDE The 76th USCI quickly proved it belonged 1 6 LIFE & LIMB More than mere accessories for the wounded 18 FROM THE CROSSROADS At Gettysburg, Pleasonton and Custer help level the field 20 SOUTHERN ACCENT Defiant Union colonel tests Kentucky’s legal system 52 TRAI LSIDE Philippi, W.Va.: Union victory brings hope—and George McClellan 56 5 QUESTIONS Ulysses Grant, from the beginning 58 R EVIEWS Liquor’s intractable reach; Sherman’s reality check 64 FI NAL BIVOUAC Unceremonious end for a distinguished veteran ON THE COVER: DESPITE HIS FLAMBOYANCE—A STAFF MEMBER DESCRIBED HIM AS “ONE OF THE FUNNIEST LOOKING BEINGS YOU EVER SAW...LOOKS LIKE A CIRCUS RIDER GONE MAD!”—GEORGE ARMSTRONG CUSTER WAS NEVERTHELESS ALL BUSINESS WHEN IT CAME TO TORMENTING HIS CONFEDERATE FOES.

Departments

Front Heroes—Part 2

look at the unforgettable wartime contributions of citizens of

stripes 32 42

Second

all

Custer rises to the occasion, J.E.B. Stuart falls in cavalry showdown outside Richmond

ACWP-230700-CONTENTS.indd 3 3/15/23 9:00 AM

Michael A. Reinstein Chairman & Publisher

Sherman Finds Personal Growth

An interview with historian Eric Burke, whose new book explores the gritty fighting culture of William Sherman’s troops in the Western Theater. historynet.com/eric-burke-interviewshermans-legacy

Weapons

Gear

The

Chris K. Howland Editor

Jerry Morelock Senior Editor

Brian Walker Group Design Director

Melissa A. Winn Director of Photography

Austin Stahl Associate Design Director

Alex Griffith Photo Editor

Dana B. Shoaf Editor in Chief

Claire Barrett News and Social Editor

ADVISORY BOARD

Gordon Berg, Jim Burgess, Steve Davis, Richard H. Holloway, D. Scott Hartwig, Larry Hewitt, John Hoptak, Robert K. Krick, Adolfo Ovies, Ethan S. Rafuse, Ron Soodalter

C ORPORATE

Kelly Facer SVP Revenue Operations

Matt Gross VP Digital Initiatives

Rob Wilkins Director of Partnership Marketing

Jamie Elliott Senior Director, Production

ADVERTISING

Morton Greenberg SVP Advertising Sales mgreenberg@mco.com

Terry Jenkins Regional Sales Manager tjenkins@historynet.com

DIRECT RESPONSE ADVERTISING MEDIA PEOPLE

Nancy Forman nforman@mediapeople.com

©2023 HISTORYNET, LLC

Subscription Information: 800-435-0715 or shop.historynet.com

List Rental Inquiries: Belkys Reyes, Lake Group Media, Inc., 914-925-2406; belkys.reyes@lakegroupmedia.com

America’s Civil War (ISSN 1046-2899) is published quarterly by HISTORYNET, LLC, 901 North Glebe Road, Fifth Floor, Arlington, VA 22203

Periodical postage paid at Vienna, VA, and additional mailing offices. Postmaster, send address changes to America’s Civil War, P.O. Box 900, Lincolnshire, IL 60069-0900

Canada Publications Mail Agreement No. 41342519 Canadian GST No. 821371408RT0001

The contents of this magazine may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of HISTORYNET, LLC.

PROUDLY MADE IN THE USA

Vol. 36, No. 2 Summer 2023

4 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR CLASSIC IMAGE/ALAMY STOCK Sign up for our FREE e-newsletter, delivered twice weekly, at historynet.com/newsletters HISTORYNET VISIT HISTORYNET.COM PLUS! Today in History

yesterday— or any day you care to search. Daily Quiz

your historical acumen—every

What If?

the fallout of historical

they gone the ‘other’ way.

What happened today,

Test

day!

Consider

events had

&

gadgetry of war—new and old— effective, and not-so effective.

TRENDING NOW ACWP-230700-MASTHEAD.indd 4 3/14/23 8:59 AM

History, Competition and Camaraderie

The N-SSA is America’s oldest and largest Civil War shooting sports organization. Competitors shoot original or approved reproduction muskets, carbines and revolvers at breakable targets in a timed match. The teams with the lowest cumulative times win medals or other awards. Some units even compete with cannons and mortars. Each team represents a specific Civil War regiment or unit and wears the uniform they wore over 150 years ago.

Competitions, called “skirmishes”, are held throughout the year in the association’s 13 regions. Members come from all over the country each spring and fall to national competitions held at the association’s home range, Fort Shenandoah, located just north of Winchester, Virginia. Skirmishing is an inclusive family sport with participation by men, women and young adults. There are even BB gun matches for the youngsters. There are also competitions for authenticity of Civil War period dress, both military and civilian in multiple categories.

Dedicated to preserving our history, period firearms competition and the camaraderie of team sports with friends and family, the N-SSA may be just right for you. If you’re a Civil War enthusiast or black powder shooter ready for our unique experience or are just in search of more information, visit our web site: www.n-ssa.org.

ACWP-230418-004 North South Skirmish PAGE.indd 1 3/13/23 2:58 PM

Historic LetTER

Regarding the article “Opportunity Knocks” about the 1864 Bermuda Hundred Campaign in your Winter 2023 issue, I thought you might find this rare battlefield order—written by Union commander Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler to his future son-in-law, Brig. Gen. Adelbert Ames—of interest. On May 13, 1864, Butler expressed hope that Ames could hold on alone against Maj. Gen. William H.C. Whiting on the left while troops commanded by Maj. Gen. Quincy Gillmore swung wide right to get at P.G.T. Beauregard’s main line.

It would be hard to find a more awkward team of commanders than Butler, Gillmore, Maj. Gen. William F. “Baldy” Smith, and Brig. Gen. August V. Kautz. They were never going to work well together and, down deep, Ulysses S. Grant knew that. But it did keep those four out of Grant’s hair for a period, and it did tie up Confederate troops that could have helped Robert E. Lee’s army closer to Richmond in the buildup to Cold Harbor.

As a Ben Butler collector, I do have a soft spot for his entire career.

Joe Normandy Catharpin, Va.

The Remarkable Dodge

I would like to commend America’s Civil War for the fine article by Judith Wilmot on Iowa Maj. Gen. Grenville Dodge (Winter 2023, P. 20). “The Unshakable Gen. Dodge,” was well-written and extremely informative. Dodge, who was from Council Bluffs, is an Iowa hero who too often has been overlooked by Civil War scholars. His service as a fighting general, a master of building and wrecking railroads, and a spymaster to Grant, Sherman, and Curtis was invaluable to the success of Union arms.

Judith’s article is filled with wonder-

ful detail and brings well-earned attention to this remarkable man.

Kenneth L. Lyftogt Cedar Falls, Iowa

Moving Article

I just got through reading Jonathan Noyalas’ Unfinished Business article in the Spring 2023 issue (P. 38). I appreciated him incorporating so many firsthand accounts into the article. Some of the soldiers’ quotes used, especially those of Generals George Custer and Frank Wheaton, were very moving. I look forward to reading future articles by Jonathan in the magazine.

Brian Mattingly Leonardtown, Md.

Editor’s Note: In our Spring 2023 issue, our Trailside column (PP. 54-56) explored Parker’s Crossroads, Tenn., site of a December 31, 1862, battle featuring Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry. After we had gone to press, the

‘Can You Hold Your Own...’

Ben Butler’s May 13, 1864, order to a subordinate, Adelbert Ames, survived the war. In 1870, Ames married Butler’s daughter, Blanche.

American Battlefield Trust announced it had completed acquisition of nearly one acre of land at the battlefield, and had helped restore it before transferring the rights to the state of Tennessee. The land saved in what had been a twoyear joint effort by the ABT and other preservation organizations is the southwest quadrant of the namesake site’s original intersection. More than 370 core acres have now been preserved at Parker’s Crossroads.

6 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR LETTERS

COURTESY JOE NORMANDY WRITE TO US E-mail: acwletters@historynet.com Letters may be edited. @AmericasCivilWar @ACWmag ACWP-230700-LETTERS.indd 6 3/14/23 8:58 AM

TODAY IN HISTORY

JANUARY 30, 1835

ANDREW JACKSON SURVIVED AN ASSASSINATION ATEMPT WHILE ATTENDING A FUNERAL AT THE U.S. CAPITOL. UNEMPLOYED HOUSE PAINTER RICHARD LAWRENCE TWICE TOOK AIM AT JACKSON, MISFIRING BOTH TIMES. IN RESPONSE JACKSON THRASHED HIM WITH HIS CANE. THE CROWD, WHICH INCLUDED U.S. REPRESENTATIVE DAVID CROCKETT, SUBDUED LAWRENCE.

For more, visit HISTORYNET.COM/TODAY-IN-HISTORY

TODAY-JACKSON.indd 22 8/25/22 6:04 PM

Our Cause, Too

Brits in Blue and Gray

OVERDUE RECOGNITION FOR MANY ACROSS THE POND WHO SERVED

Learning there are more than 520 Civil War veter ans interred in mostly unmarked graves in the United Kingdom, the Monuments for UK Veterans of the American Civil War Association formed in Essex, England, in January 2022. Gina Denham, who co-founded the association with Darren Raw lings, discovered that her great-great-grandfather, George Denham, had served during the war on the Union ironclad Chickasaw and later in the 111th Pennsylvania Infantry before returning to his homeland. With aid from the U.S. government, Gina secured a headstone for her ancestor’s previously unmarked gravesite.

Through their research efforts, Denham and Rawlings were able to confirm the identify of another somewhat forgotten British Civil War veteran once in terred in an unmarked grave in his homeland: Maurice Wagg, a Medal of Honor recipient from Christchurch in southern England. Born July 23, 1840, Wagg was coxswain on USS Rhode Island, involved in the rescue of crewmembers on the famed USS Monitor as it foundered off the North Carolina coast on December 31, 1862.

Credited with saving the lives of four of Moni’s officers and 12 crewmen, Wagg would be promoted to the rank of acting master’s mate. He and six other Rhode Island sailors were the first individuals to receive the Medal of Honor for a non-combat action.

Wagg returned to England after the war and helped form the London Branch of American Civil War Veterans, attending its inaugural meeting on September 20, 1910. On June 22, 1926, Wagg died at his home in Poplar, East London. With the help of author/researcher Michael Hammerson, an official headstone for his grave was obtained in 2015. (Hammerson has helped uncover the identity of a number of other Civil War veterans and their final resting places.)

In its first year of operation, the association raised $3,500 for construction of a monument that will recognize the contributions of these Civil War vets from the United Kingdom—many, like Wagg and Denham, all but forgotten to history. To help, visit www.justgiving.com/crowdfunding/ themonumentalproject

8 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR A Blast of Civil War Stories GRAPESHOT! COURTESY RICHARD H. HOLLOWAY; RIGHT: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS COURTESY GINA DENHAM

ACWP-230700-GRAPESHOT.indd 8 3/14/23 4:33 PM

Maurice Wagg (circled) and fellow countrymen who filled the ranks on land or sea in the seminal U.S. struggle pose outside London’s Ragged School Mission Hall. Wagg proudly dons his Medal of Honor (another sample of one shown below).

CIVIL WAR ILLUSTRATED

Penned in 1855, William J. Hardee’s “Hardee’s Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics” was used by both sides during the Civil War. Hardee, a Georgian by birth, controversially decided to fight for the Confederacy. That particularly angered one Northern artist, who lambasted the former U.S. Army officer’s renowned manual, portraying it in a cartoon as antiquated and useless in “modern” warfare. The exaggerated illustration appeared in a newspaper early in the war. “Old Reliable” likely wasn’t too bothered being mocked.

Preservation News

Five critical Western Theater battlefield sites in four states—Shiloh in Tennessee; Chickamauga in Georgia; Brice’s Cross Roads in Mississippi; and Bentonville and Wyse Fork in North Carolina—are the focus of a new American Battlefield Trust preservation effort. At stake are an endangered 343 acres, including 159 at Bentonville, 95 at Brice’s Cross Roads, and 86 at Wyse Fork. ¶ With help from organizations such as the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation and the American Battlefield Protection Program, the ABT has had recent victories in Virginia with the Gaines Mill–Cold Harbor Saved Forever Campaign and preservation of 47 acres at Cedar Creek and Cedar Mountain. Go to battlefields.org for more info.

QUIZ

Before Custer Went West

Match the future Civil War general with his prewar hostilities.

A. Albert Sidney Johnston

B. John Bell Hood

C. George Pickett

D. Nathaniel Lyon

E. J.E.B. Stuart

F. John C. Frémont

G. Robert E. Lee

H. Samuel B. Heintzelman

I. Henry Heth

J. Philip H. Sheridan

1. Wounded fighting Cheyenne Indians, Solomon River, Kansas, 1857

2. Confronted British at San Juan Island, 1859

3. Massacred Brulé Lakota at Ash Hollow, Neb., 1855

4. Wounded fighting Cascade Indians, 1856

5. Fought Yuma Indians along Gila River, Calif. and Ariz., 1852

6. Led expedition against Mormons in Utah, 1857

7. Wounded fighting Comanche Indians, Devil’s River, Texas, 1857

8. Massacred up to 500 Wintu in Sacramento Valley, 1846

9. Wounded at Chapultepec, Mexico, 1847

10. Massacred Pomo Indians at Bloody Island, Calif., 1850

Answers: A.6, B.7, C.2, D.10, E.1, F.8, G.9, H.5, I.3, J.4.

SUMMER

COURTESY RICHARD H. HOLLOWAY; RIGHT: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS COURTESY GINA DENHAM

George Pickett

2023 9

ACWP-230700-GRAPESHOT.indd 9 3/14/23 4:33 PM

CONVERSATION PIECE

Fine China

While assigned to Louisiana in the summer of 1865 (see “Summer of Discontent,” P. 22), George and Libbie Custer visited the New Orleans studio of photographer and portrait artist R.T. Lux. Custer commissioned Lux to craft the porcelain vases shown here. Lux used tintype photos he had taken of the couple to hand-paint their images on the vases, each 11 inches tall and dated July 1865. When first sold at auction by Butterfield & Butterfield in 1995, the Libbie vase had been damaged—a number of broken pieces glued back together “with no attempt to cover the break lines.” That would be rectified prior to a subsequent auction in 2010, where the collectibles fetched $53,999.99.

BATTLE RATTLE

From Custer to Lincoln

Bruce K. Lawes is most noted for his wildlife artwork, but his astonishing Civil War paintings also can be found on his website, bklawesart.com—tributes to his late brother, who first took him to Gettysburg. (His painting “Brothers in Arms” was the official poster of the battle’s 150th anniversary.) Adolfo Ovies, who wrote our Battle of Yellow Tavern article on P.32, has long admired Lawes’ painting of Custer at East Cavalry Field, “Before the Storm,” and Lawes’ art graces the covers of Ovies’ The Boy Generals trilogy on Custer, Wesley Merritt, and the Army of the Potomac cavalry. Above is a recent Lawes work, “A New Birth of Freedom,” portraying a meditative Lincoln crafting his Gettysburg Address.

10 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR GRAPESHOT! FROM TOP: ERIC LEE/WASHINGTON POST/GETTY IMAGES; THE HORSE SOLDIER; RICHARD H. HOLLOWAY COLLECTION CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: HERITAGE AUCTIONS, DALLAS, TEXAS; BRUCE K. LAWES; BENTLEY HISTORICAL LIBRARY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

“Custer was a fighting man, through and through, but wary and wily as brave. There was in him an indescribable something— call it caution, call it sagacity, call it real military instinct—it may have been genius— by whatever name entitled, it nearly always impelled him to do intuitively the right thing.”

—James H. Kidd, 6th Michigan Cavalry

ACWP-230700-GRAPESHOT.indd 10 3/14/23 4:34 PM

A Singular Honor

Lewis A. Bell probably didn’t have much time to contemplate what he was doing. It was October 21, 1861, and Bell found himself in the midst of the frantic Union retreat toward the Potomac River late in the Battle of Ball’s Bluff. As a Black man, he was not authorized at this stage of the war to fire a gun in combat. Merely a camp worker, he had crossed the river alongside members of the 15th Massachusetts Infantry in what had initially been a scouting mission. Now, with Confederate soldiers swarming in his direction, he picked up a gun and began firing.

Bell’s feat that day has long been overshadowed in histories of the war. It is believed, however, that he was the Civil War’s first Black combatant, and in February a wayside marker was unveiled in his honor during a ceremony at the 76-acre battlefield park just north of Leesburg, Va.

“On this territory he’s considered chattel,” Cate Magennis Wyatt, NOVA Parks chair, told ceremony attendees. “He’s got a choice to make. There are rifles, which if he picks up, he could be imprisoned in the North….And if he’s caught and tries to run, he could be lynched.”

Making History

Bell and other members of the 15th Massachusetts would eventually be captured and imprisoned in Richmond before being exchanged in February 1862. Little is known about him from that point on, and it is uncertain whether he joined the Union Army after the Emancipation Proclamation or even survived the war. His singular achievement at Ball’s Bluff is, at least, finally getting some acclaim.

By October, Roden had been elevated to command of Company B. His unit would serve in all three theaters during the war. During the Chancellorsville Campaign, Roden again received accolades from his commander when he attacked and burned 18 Confederate wagons. Sickness, however, would follow Roden, finally forcing him to resign from service on April 21, 1864. His sword and iron scabbard survive, a testament to the dependability of what was known as an “Old Wristbreaker.” Designed to slash the enemy, the heavy flatbacked blade was originally created to replace the ineffective Model 1833 Dragoon Saber.

The 12th Illinois Cavalry mustered into the Union Army in Springfield, Ill., on February 24, 1862. A 29-year-old German immigrant, now going by the Anglicized name Charles Roden, was elected first lieutenant of Company D. After signing up, each man was issued a U.S. Model 1840 cavalry saber; Roden had his engraved lieut. c. roden.

In an official report on September 9, 1862, Roden received credit from the regiment’s commander, Colonel Arno Voss, for his role in a pre-Antietam engagement at Martinsburg, Va. Wrote Voss: “On the morning of the 4th instant, Lieut. Charles Roden....having ten men with him behaved very gallantly.”

Recently sold to an anonymous private collector by The Horse Soldier in Gettysburg, Roden’s sword showed heavy usage during the war. Drawn, the sword is 40 inches in length. The curved blade measures about 34½ inches. The engraved grip is a rounded wooden piece covered in leather and affixed to the handle with brass wire. The scabbard and blade all have a light patina from age.

Albert R. LaBure

Albert R. LaBure

SUMMER 2023 11 FROM TOP: ERIC LEE/WASHINGTON POST/GETTY IMAGES; THE HORSE SOLDIER; RICHARD H. HOLLOWAY COLLECTION CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: HERITAGE AUCTIONS, DALLAS, TEXAS; BRUCE K. LAWES; BENTLEY HISTORICAL LIBRARY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

‘Wristbreaker’

GRAPESHOT!

ACWP-230700-GRAPESHOT.indd 11 3/14/23 4:34 PM

NOVA Parks Chair Cate Magennis Wyatt (center) and other attendees at the Bell marker’s unveiling ceremony.

‘All Brave Men Could Do’

BY THE END OF THE WAR, THE 76TH USCI LEFT NO DOUBT IT BELONGED

By Edward Windsor

IN LATE 1862, Horace Washington and Olmsted Massy, former slaves from Virginia, met with a recruiting officer in New Orleans to join the 4th Louisiana Native Guards. The 4th was one of four infantry regiments formed as part of the Louisiana Militia in 1861 to protect New Orleans from Yankee invaders, its initial members free men of color pulled from the Crescent City itself. New Orleans’ capitulation to U.S. Navy Flag Officer David G. Farragut in April 1862, however, did not end the war for the free black soldiers of the 4th Native Guards or the other three regiments, who readily agreed to join the Union Army. After Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler assimilated the regiments into his military chain of command, recruitment was opened to former slaves, hence Washington’s and Massy’s desire to serve. The two men were mustered in as corporals. At first, Butler used the Native Guard only to conduct guard duty in the vicinity. Eventually they were assigned to protect government facilities in Baton

Picket Duty

Early in the war, free men of color and former enslaved men joined the Louisiana Native Guards, shown here guarding a railroad outside New Orleans in 1863.

Rouge, but on May 27, 1863, the regiments joined Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks’ troops in combat while storming the Confederates’ Mississippi River stronghold at Port Hudson, La. Though unsuccessful, the black troops proved their mettle in battle.

A week later, the Native Guard regiments were reorganized and given new designations. The 4th was now known as the 4th Regiment U.S. Infantry, Corps d’Afrique— assigned to the 19th Corps’ 1st Division in the Department of the Gulf. After the surrender of Port Hudson on July 9, 1863, the 4th was stationed there to guard captured stores but was soon ordered to garrison Forts Jackson and St. Philip below New Orleans. Duty at those riverside forts was pleasant, as civilians in small boats constantly stopped by to sell the soldiers fresh-picked oranges for a penny each. But on February 20, 1864, the unit was transferred back to Port Hudson.

Another new designation would come a few weeks later. Now known as the 76th United States Colored Infantry, under Colonel Charles W. Drew’s command, the regiment formally became part of the Union Army. That certainly produced a measure of pride for the men in the ranks.

Besides guarding the smaller guns captured at Port Hudson, as the larger weapons had already been removed, the 76th was ordered to man them in case of attack by local Confederate cavalry units. Their post commander, Brig. Gen. John P. Hawkins, complained they were being stretched too thin, however. “There are 367 men in the regiment for duty,” he carped, “which barely supplies sentinels over the guns—the camp guard— with a few remaining for detachment drill at the pieces.”

In February 1865, the 76th served under Hawkins, now commanding a division of USCI troops at Algiers, La., near New Orleans. The 76th was put into the 3rd Brigade of Hawkins’ Division, alongside the 48th and 68th USCI. After a short stint, the 76th was

12 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR REGIMENTAL PRIDE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

ACWP-230700-REGIMENTAL.indd 12 3/14/23 4:32 PM

transferred to Barrancas, Fla., temporarily becoming a part of the Federal District of West Florida.

Pensacola was its next destination—the port city in Florida’s panhandle serving as a jumping-off point to assist in the capture of Mobile. Major General E.R.S. Canby (Hawkins’ brother-in-law) assembled as many troops as he could to overtake the largest coastal city still in Confederate hands.

The boredom of constant inactivity in guarding facilities and cities was grating on the troops, who understandably wanted to see some action. At Mobile, their wishes would be granted. Following a few weeks of manning the trenches surrounding the city, the men were informed they were to participate in an upcoming assault on Fort Blakeley.

Wrote Drew:

On the night of April 1, my brigade [including the 76th, currently commanded by Major William E. Nye] was ordered to encamp in line of battle to the right of the Stockton road about two miles and a half from the enemy’s works, which was done in the following order: The Sixty-eight Regiment on the right, the Seventy-Sixth in the center, and the Forty-eighth on the left, the command occupying the advance and extreme right.

The next morning about 7:30 our pickets becoming warmly engaged, I formed line as quickly as possible, when I received an order to advance in line of battle. I immediately ordered two companies from each regiment deployed forward as skirmishers, and commenced the advance, which was continued for two miles through a thickly wooded and broken country, my skirmishers fighting about half the way.

about half a mile from the works of the enemy, my right resting on the swamp and my left connecting with General [William A.] Pile’s brigade….

76th U.S. Colored Infantry [4-Year]

Previous Designations

4th Regiment, Louisiana Native Guards (La. Militia); 4th Regiment, Louisiana Native Guards (U.S.); 4th Regiment, Corps d’Afrique

Once halted, Drew’s units began construction of a fortification they named Battery Wilson. A battery of Union artillery moved in behind their position and began bombarding the Confederate position with their four 30-pounder Parrott guns. The artillery pieces later turned their attention to the Confederate gunboats Huntsville and Nashville coming up from Mobile Bay. The noise must have been deafening to the 76th and the rest of their brigade with cannon fire in front of and behind them.

On April 9, Drew noted:

Assigned

La. Militia/19th Corps/ Department of the Gulf/ District of West Florida/ Military Division of Western Mississippi

Mustered In New Orleans, La. Active

1861–December 31, 1865

Total Served 664

Total Casualties 82

Notable Engagements

Occupation of New Orleans; Garrison of Forts Jackson and St. Philip, La.; Siege of Port Hudson, La.; Fort Blakeley, Ala.

Notable Figures

Sgt. Olmsted Massy; Corporal Horace Washington; Captain Frederick Grant; Major William E. Nye; Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) Charles Wilson Drew

Notwithstanding the numerous obstacles in the way, there was scarcely a break in the line the whole distance. The precision maintained by the line, as well as the bold and steady advance of the skirmishers under heavy fire, were sufficient, I think, to command the admiration of all. Arriving within half a mile of the works I received an order to halt, which was at once communicated to the skirmish line. Our position was then immediately in rear of a ravine

I ordered the Sixty-eight and Seventy-Sixth Regiments (then in the trenches) to double their skirmish lines at 5 p.m. and drive the enemy from his rifle-pits, and if necessary to do it I should order out the regiments entire. Before the work was fairly commenced, however, I heard cheering on my left and saw the skirmishers of the First Brigade advancing. I immediately gave the command forward and forward the entire command (except the Fortyeighth Regiment left in reserve) swept with a yell….Before I could get up with the regiment they had fallen back to the abatis, and when the charge became general they, with the rest, went forward with a shout and did all that brave men could do. The result was soon accomplished and Blakely [ sic ] was ours. I cannot speak in terms of too much praise of the officers and men of my command. Each and every one did willingly all that was asked, working incessantly night and day a large portion of the time. The support and assistance rendered me by regimental commanders entitles them to my warmest gratitude. I could ask for none better.

“The loss suffered by my command from the investment of the place [Mobile] until its capture is 2 officers killed and 3 wounded; enlisted men, 12 killed and 65 wounded,” noted Major Nye.

SUMMER 2023 13 REGIMENTAL PRIDE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

ACWP-230700-REGIMENTAL.indd 13 3/14/23 4:32 PM

The unit occupied Mobile for only a day before making a 12-day march to Montgomery, the Confederacy’s original capital. In June, they were directed to return to New Orleans. Major General Philip Sheridan then had them board steamers to Alexandria, La., to join forces that Maj. Gen. George Armstrong Custer was assembling for a mission in Texas (see P. 22).

Though not directly part of Custer’s cavalry division in Alexandria, the 76th and the 80th USCI would receive directives from the flamboyant general. Both regiments were to keep the peace in the town and guard governmental stores while Custer tried to train and have several Union cavalry units from different stations in the South work together as a cohesive group before departing for Texas.

Because of the exhaustive summer heat in central Louisiana, Custer had his troopers build brush arbors atop their canvas tents to lessen the sunlight beating down on them. The African American troops were ordered to occupy the cabins across the Red River in Pineville that had been erected by the Confederate forces occupying Forts Randolph and Buhlow in the winter of 1864-65.

“The men hastily constructed small cabins with pine boards [as well as chimneys for cooking],” recalled Confederate Major Winchester Hall. Noted Augustus V. Ball, a surgeon in McMahan’s Texas Battery, which occupied Pineville until their surrender on June 3, 1865, the structures were “roomy and spacious but they leaked badly and flooded frequently.”

Pineville was considerably smaller than Alexandria but was spared the burning of its counterpart town across the river by retreating Federal forces in mid-1864. The smaller town did not contain much to look at other than small businesses and the Mount Olivet Episcopal Church on Main Street. The large hog-processing building was vacant, an empty symbol of more prosperous times.

‘I Could Ask For None Better’

Soldiers in the 4th Regiment U.S. Infantry, Corps d’Afrique, which became the 76th USCI, conduct artillery drills at Port Hudson, La., after its capture in July 1863.

Left:

Though the works at the two forts were surrounded by massive walls, it wasn’t what the men hadn’t already seen at Port Hudson and Mobile. Something unique, however, was right there in the river in front of them. Being whisked away after only a day inside Mobile, the 76th did not have a chance to get a close look at the Confederate naval craft there. But moored in the river in front of the two forts was the infamous CSS Missouri. Tasked with guarding the ironclad that had struck fear in many Union naval commanders, the soldiers were able to get a closer look on a daily basis.

No major incidents with the civilian population in the area occurred on the 76th’s watch. The unit had more than 300 men present for duty and spent most of the time with repetitive drill, just like the Confederates in the vicinity had done when they were here earlier in the year.

In August the 76th would be sent to its final post: Greenwood, La., outside Shreveport. As their time there wound down, Olmsted Massy, now a sergeant, placed an advertisement in the Philadelphia-based Christian Recorder attempting to locate his wife, Nancy, as he was ready to start a new life as a free man in New Orleans. “She was born and raised in Gochland County, Va.,” the advertisement read. “She was owned, about 15 years ago by John Mickey. Her name before marriage was Nancy Brown.”

The 76th officially disbanded on December 31, 1865.

14 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR REGIMENTAL PRIDE

FROM TOP: CORBIS/GETTY IMAGES; U.S. ARMY HERITAGE AND EDUCATION CENTER

Colonel Charles W. Drew, the regiment’s commander late in the war.

ACWP-230700-REGIMENTAL.indd 14 3/14/23 4:47 PM

Edward Windsor writes from Corinth, Miss.

Hunting is our heritage, our heart, and our future.

Hunting is our heritage, our heart and our future.

A DEFINITIVE STUDY OF THE MIND, BODY, AND ECOLOGY OF THE HUNTER IN THE MODERN WORLD

Where does hunting fit in the modern world? To many, it can seem outdated or even cruel, but as On Hunting affirms, hunting is holistic, honest, and continually relevant. Authors Lt. Col. Dave Grossman, Linda K. Miller, and Capt. Keith A. Cunningham dive deep into the ancient past of hunting and examine its position today, demonstrating that we cannot understand humanity without first understanding hunting.

Readers will…

• discover how hunting formed us,

• examine hunting ethics and their adaptation to modernity,

• understand the challenges, traditions, and reverence of today’s hunter,

• identify hunting skills and their many applications outside the field,

• learn why hunting is critical to ecological restoration and preservation, and

• gain inspiration to share hunting with others.

Drawing from ecology, philosophy, and anthropology and sprinkled with campfire stories, this wide-ranging examination has rich depths for both nonhunters and hunters alike.

On Hunting shows that we need hunting still—and so does the wild earth we inhabit.

“All true hunters ‘feel’ the truth, but few are able to ‘articulate’ that truth. Now, thankfully, we have On Hunting to be our champion of the wild!”

Order your copy today at GrossmanOnTruth.com ACWP-230418-007 Grossman on Truth Book.indd 1 3/20/23 10:26 AM

—JIM SHOCKEY, Naturalist, Outfitter, TV Producer and Host

The nonprofit NMCWM, based in Frederick, Md., explores the world of medical, surgical, and nursing innovation during the Civil War. To learn more about the stories explored in this and future columns, visit

Medicine Bags

A SURGEON’S SADDLEBAGS HELD VITAL ANESTHETICS AND FIELD REMEDIES

WHEN J. NEWTON ARNOLD enlisted as an assistant surgeon in the 113th New York Infantry in December 1862, he expected to go to the front. Instead, his regiment was converted to the 7th New York Heavy Artillery and spent the next year-and-a-half on garrison duty around Washington, D.C.

The young doctor (only 27 at the time) and his comrades got their wish in May 1864 when they were called up to join Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Potomac. Within four months, the regiment had lost 68 percent of its men killed, wounded, or missing.

Looking at Arnold’s worn saddlebags, pictured here and on display at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, it’s easy to imagine the horror in which they were part. He undoubtedly rode hard between dressing stations and hospitals to attend the many wounded.

Each pouch had been filled with metal or glass vials, most likely carrying opiates such as morphine or opium powder, though they may also have contained quinine or other common medications. As the only truly effective painkillers, opiates were doled out by surgeons in staggering quantities.

The saddlebags are embossed with gold, showing the pride Arnold had for his kit. One pouch is embossed “Surgeon J.N. Arnold,” and the other “7th N.Y.H.A.”

LIFE & LIMB

COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF CIVIL WAR MEDICINE ACWP-230700-LIFEANDLIMB.indd 16 3/14/23 8:59 AM

The Day the War Was Lost It might not be the one you think Security Breach Intercepts of U.S. radio chatter threatened lives 50 th ANNIVERSARY LINEBACKER II AMERICA’S LAST SHOT AT THE ENEMY First Woman to Die Tragic Death of CIA’s Barbara Robbins HOMEFRONT the Super Bowl era WINTER 2023 WINTER 2023 Vicksburg Chaos Former teacher tastes combat for the first time Elmer Ellsworth A fresh look at his shocking death Plus! Stalled at the Susquehanna Prelude to Gettysburg Gen. John Brown Gordon’s grand plans go up in flames MAY 2022 In 1775 the Continental Army needed weapons— and fast World War II’s Can-Do City Witness to the White War ARMS RACE THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF MILITARY HISTORY WINTER 2022 H H STOR .COM JUDGMENT COMES FOR THE BUTCHER OF BATAAN THE STAR BOXERS WHO FOUGHT A PROXY WAR BETWEEN AMERICA AND GERMANY PATTON’S EDGE THE MEN OF HIS 1ST RANGER BATTALION ENRAGED HIM UNTIL THEY SAVED THE DAY JUNE 2022 JULY 3, 1863: FIRSTHAND ACCOUNT OF CONFEDERATE ASSAULT ON CULP’S HILL H In one week, Robert E. Lee, with James Longstreet and Stonewall Jackson, drove the Army of the Potomac away from Richmond. H THE WAR’S LAST WIDOW TELLS HER STORY H LEE TAKES COMMAND CRUCIAL DECISIONS OF THE 1862 SEVEN DAYS CAMPAIGN 16 April 2021 Ending Slavery for Seafarers Pauli Murray’s Remarkable Life Final Photos of William McKinley An Artist’s Take on Jim Crow “He was more unfortunate than criminal,” George Washington wrote of Benedict Arnold’s co-conspirator. No MercyWashington’s tough call on convicted spy John André HISTORYNET.com February 2022 CHOOSE FROM NINE AWARD - WINNING TITLES Your print subscription includes access to 25,000+ stories on historynet.com—and more! Subscribe Now! HOUSE-9-SUBS AD-11.22.indd 1 12/21/22 9:34 AM

No Slow Trot

JOE HOOKER HAD HIS SHORTCOMINGS. BUT WHAT HE DID IN REVITALIZING HIS ARMY’S CAVALRY CORPS WAS MONUMENTAL

By D. Scott Hartwig

THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC’S cavalry received a muchneeded reorganization when Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker assumed command of the Union’s largest army in the winter of 1863, transforming from a collection of mounted brigades to a formal Cavalry Corps. Most important perhaps, Hooker infused his horsemen with a new mission. Although they would continue fulfilling the traditional cavalry roles of scouting, picketing, headquarters security, and escort duty, they were now to serve primarily as an offensive weapon—much like J.E.B. Stuart’s vaunted troopers did in the Army of Northern Virginia.

During the Chancellorsville Campaign, Union cavalry performed better in defeat than it had in any previous campaign, but Hooker was disappointed in the leadership of some of its commanders, specifically corps commander George Stoneman and 2nd Division commander William A. Averell. Both lost their jobs in a further reorganization that followed Chancellorsville.

The Cavalry Corps’ new commander would be Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, known as a notorious self-promoter and miserable intelligence officer but someone Hooker believed might put more fire into his troopers. Pleasonton did. In the early stages of the Gettysburg Campaign in

June 1863, the Federal horsemen took the fight to the Rebel cavalry at Brandy Station, Va., and in a subsequent series of sharply fought engagements at Aldie, Middleburg, and Upperville in central Virginia.

Nevertheless, though his men had fought well, Pleasonton was eager to find positions for his more aggressive subordinates. After Maj. Gen. Julius Stahel’s division was sent as reinforcements from the defenses of Washington, D.C., in late June, Pleasonton convinced the Army of the Potomac’s new commander, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, to allow him to replace Stahel and his brigade commanders with officers of his own choice.

A Lit Fire

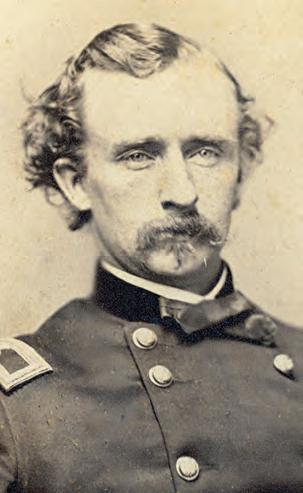

Pleasonton handed Stahel’s command to the recklessly aggressive Brig. Gen. H. Judson Kilpatrick, and to fill the two brigade slots he received approval to jump two junior officers—Elon Farnsworth and George Armstrong Custer—to brigadier general. Both men had been staff officers for Pleasonton and were favorites of the general.

Alfred Pleasonton (right), a brigadier general at this point, poses with one of his favorites, George Custer, who was quick to reward the general’s faith in him.

Also elevated was Captain Wesley Merritt, who was handed a brigade in the cavalry’s 1st Division. All were young, bright, and aggressive officers.

Farnsworth never had a chance to prove himself, for he was killed July 3 at Gettys-

18 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR FROM THE CROSSROADS LITTLE BIGHORN BATTLEFIELD NATIONAL MONUMENT, NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NOEL KLINE

ACWP-230700-CROSSROADS.indd 18 3/14/23 9:35 AM

burg in a foolish attack demanded by Kilpatrick. Merritt proved an excellent soldier, but it is Custer we remember best. Because of the Little Big Horn showdown that lay in his future, Custer is remembered as a brash, ambitious, and particularly reckless officer. He was indeed brash and ambitious. His performance during the Gettysburg Campaign, however, showed an officer who understood modern cavalry tactics and applied them appropriately while displaying solid leadership commanding volunteers.

The 23-year-old Custer was, in fact, far more prudent than popular history would have us think. He asked for and received command of a brigade of four Michigan regiments: the 1st, 5th, 6th, and 7th. When he arrived in the camps of his brigade in the rain on June 29, Custer’s appearance instantly attracted attention—as he intended. A staff officer described him as “one of the funniest looking beings you ever saw, and looks like a circus rider gone mad! He wears a huzzar jacket and tight trousers, of faded black velvet trimmed with tarnished gold lace.” Not to mention a red cravat.

Ego partly drove Custer’s uniform style, but it also reflected his understanding of volunteer soldiers. They would recognize him instantly on the march or, more importantly, on the battlefield, where he intended to provide them leadership that would inspire them to risk their lives and take the fight to the enemy.

The day after assuming command of his brigade, June 30, Custer’s command engaged J.E.B. Stuart’s Confederate horsemen for the first time at Hanover, Pa. Instead of charging headlong into the fray, heedless of casualties, Custer demonstrated tactical competence, employing his superior firepower—the 5th and 6th Michigan carried Spencer repeaters—by dismounting his troopers and supporting them with attached horse artillery. The result was a check to the Rebel horsemen, who departed to find an easier route to reach Lee’s main army.

On July 2, Custer’s Michiganders encountered Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton’s veteran brigade near the small village of Hunterstown, Pa., several miles northeast of Gettysburg. When the officer leading Custer’s van emerged from the village, he encountered open ground extending west for several hundred yards. Standing partway across these open fields were two farms around which a small rearguard of Hampton’s Brigade had halted to keep the enemy at a distance from the main body.

Uncertain what this small body of enemy cavalry represented, Custer dismounted several companies of the 6th Michigan and unlimbered his horse artillery to provide covering fire. But to disperse the Confederate horsemen, he ordered Company A of the 6th to conduct a mounted charge. Then, as the company readied for its advance, Custer drew his saber and motioned for his staff to stay back before riding out in front of the troopers. With what would be described as a “careless laughing remark,” he declared, “I’ll lead you this time boys. Come on!’”

The charge struck the Confederates hard. Reinforcements from Hampton’s Brigade counterattacked and a wild melee ensued. Custer’s horse was killed beneath him, and he was almost ridden down and killed by a Southern trooper—his life saved by his orderly, who dropped the assailant with a well-aimed shot.

Custer’s prudence in establishing an additional line of fire was rewarded when his dismounted troopers and horse artillery held off Hampton’s counterattack. Though Custer had taken an unnecessary risk in leading the charge, the calculated risk paid dividends in increased confidence and respect for the young general’s leadership.

A day later, Custer made even more of a mark with his men and the army in the much larger cavalry action three miles east of Gettysburg around the John Rummel Farm. Again, Custer displayed a firm grasp of cavalry tactics, skillfully using his troopers in both dismounted and mounted roles, and establishing his horse artillery as a base of fire. And again, Custer deliberately placed himself in harm’s way by leading charges by the 7th and then the 1st Michigan Cavalry. In both charges he rode out in front of his men shouting, “Come on, you Wolverines!” The result was a block of Stuart’s efforts to disrupt the Army of the Potomac’s communication lines.

Custer had accomplished precisely what Pleasonton had sought in advancing these young men to brigade command. It elevated the Union cavalry to the level of J.E.B. Stuart’s. That process had actually begun a few weeks earlier at Brandy Station, but now the Army of the Potomac’s horsemen would be an effective fighting arm. The attrition of two more years of war meant that the men in blue would, however, gradually gain superiority.

SUMMER 2023 19 FROM THE CROSSROADS

LITTLE BIGHORN BATTLEFIELD NATIONAL MONUMENT, NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NOEL KLINE

Scott Hartwig writes from the crossroads of Gettysburg.

Wolverine Wonder

ACWP-230700-CROSSROADS.indd 19 3/14/23 9:35 AM

The towering monument to George Custer’s Michigan Brigade in East Cavalry Field, site of its Day 3 Gettysburg laurels.

Freedom Flight

A so-called “fugitive slave” arrives at a Union military encampment and purported freedom, in an illustration by Edwin Forbes.

‘Concealed in the 92nd’

NORTHERN COLONEL WIELDS THE POWER OF THE MILITARY TO ENFORCE EMANCIPATION

By Daniele Celano

IN NOVEMBER 1862, Marcus Thompson escaped from a farm in Mount Sterling, Ky., to a nearby Union military camp commanded by Colonel Smith D. Atkins of the 92nd Illinois Infantry. Along with 29 other enslaved men, women, and children, Marcus had been farming the fields of a wealthy estate known for its corn and butter production, owned by the elderly Mary Thompson, who, it was clear, was not prepared to accept Marcus’ flight to freedom and teamed with her neighbors in suing Colonel Atkins. The lawsuit would test the legal bounds of emancipation through the military.

A year earlier Atkins, an antebellum lawyer, had abruptly departed in the middle of a criminal case in Freeport, Ill., to answer President Abraham Lincoln’s call for troops after the firing on Fort Sumter. The newly minted state attorney, who worked intermittently as a local newspaper editor, had passed the bar five years earlier.

Energized by the potential of the fledgling Republican Party, Atkins had actively cam-

paigned for Lincoln in 1860. Not all Unionists agreed on the fate of slavery, of course, but Atkins was a fierce abolitionist, believing that emancipation would finally fulfill promises of national equality by the Founding Fathers. In a speech condemning the Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decision, Atkins posited that warfare would be the only solution to secure a truly free nation.

Fugitive slaves were a particular concern in Kentucky, bordered to the north by the free states of Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana. Numerous state and federal laws criminalized slave flight and prohibited people from aiding and concealing runaways. Under various property laws, slave owners could sue antislavery reformers, and Underground Railroad conductors were often accused of stealing their “property.”

When war erupted in April 1861, Kentucky remained in the Union, and many politicians cited the Constitution’s “Fugitive Slave” clause as a key condition for it. Slaves nevertheless used familiar escape routes and

20 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR SOUTHERN ACCENT USAHEC MOUSEION ARCHIVES/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Southern Accent is produced in partnership with the Nau Civil War Center at the University of Virginia, which promotes scholarship, teaching, and public outreach regarding the United States in the Civil War era. It draws upon UVA’s rich resources, faculty, and students.

ACWP-230700-SOUTHERN.indd 20 3/14/23 9:35 AM

Underground Railroad networks to abscond to Union fortifications. Seizing upon that, the U.S. government passed legislation in 1861-62 freeing fugitive slaves who made it to Army outposts. If the Confederacy considered slaves property, Congress would reason, the U.S. military had the authority over their slaves as contrabands of war.

Even though Congress granted emancipation to all Confederate “contrabands,” the policy threatened to reinforce the controversial interpretation of the enslaved as “property.” This proved especially difficult to navigate in Kentucky. The state had not seceded, and federal authority to invoke the contraband policy in Union territory, at the expense of loyal citizens, remained in question.

The November 1862 conflagration involving Atkins actually was ignited by a Union captain who complained to Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger about three slaves hiding within the 92nd Illinois’ lines. Those slaves—Cyrus, Henry, and Mosely— purportedly belonged to the Union captain’s uncle, Charles Gilkey.

Upon inquiry, Atkins declared he would not release any enslaved person against his or her will, which spurred Gilkey, Mary Thompson, and nearly a dozen other neighbors to retain the prestigious Robertson law firm to bring lawsuits against Atkins. On November 19, backed by armed townspeople, the Mount Sterling sheriff served a summons and “order for delivery of property” against Atkins in an attempt to forcibly remove Marcus Thompson—as well as Cyrus, Henry, Mosely, and a number of other slaves, ages 18 to 27—from the camp.

Fayette Circuit Court.

Mary Thompson against } Order for Delivery of Property

Smith D. Atkins

him the slave Marcus. Said Atkins denied that he had possession of said slave but when charged that he was concealed in the 92 Regt of Illinois vol Infantry USA of which said Atkins is Colonel he did not deny the fact but stated that No officer of the law or other person should search for or take from the camp of his regiment this or any other slave. If attempted the officer would be shot. With the posse the Sheriff was able to summon it was impossible to get possession of or search for said slave.

C.S. Bodley S.F.C.

The plaintiffs made sure to frame their suits around property loss, complete with appraised monetary value for each man, naming Atkins as the thief. The petitions demanded immediate repossession and damages, or, if the sheriff could detain them, judgment for the enslaved men’s value. Although the court ordered Atkins to answer the petition, he refused, which spawned affidavits demanding his compliance. The colonel continued to stand firm, however. In turn, a jury awarded Mary Thompson $625, with an additional $25 in damages. Her fellow plaintiffs secured similar judgments, some as high as $800 per slave, with damages as high as $50.

Besides his time in Kentucky with the 92nd and later with Sherman’s armies, Atkins fought at Fort Donelson and Shiloh.

The Commonwealth of Kentucky, to the Sheriff of Fayette County: YOU are commanded to take the slave Marcus, copper color & 27 years old & medium size, and of the value of Eight Hundred Dollars, from the possession of the Defendant Smith D. Atkins, and deliver him to the Plaintiff, Mary Thompson, upon her giving the Bond required by law: and you will make due return of this order on the 1st day of the next February Term of the Fayette Circuit Court.

Witness: Jno B. Norton, Clerk of said Court, this 18 day of Nov, 1862

Executed Nov 19th 1862 by delivering to S.D. Atkins a true copy of the within order of delivery and demanding of

The judgments totaled more than $12,000, and Atkins feared his property in Illinois could be auctioned off by a court ruling while he was away fighting. Leaving Kentucky later in the war did not end Atkins’ legal troubles either. In August 1864, he was charged with “slave harboring,” by the state’s Montgomery Circuit Court, a judgment carrying a possible sentence of 2–20 years. Despite the indictment, Atkins was never arrested.

The January 1863 Emancipation Proclamation authorized the recruitment of African Americans in the U.S. military. Kentucky and four other border states were exempted from the proclamation’s stipulation that all slaves in Confederate territory were to be freed.

The 92nd Illinois took part in the June-July 1863 Tullahoma Campaign, and Atkins commanded a cavalry brigade during the 1864 March to the Sea and then oversaw the surrender of Chapel Hill, N.C., in April 1865. He ended the war a brevet brigadier general.

In May 1864, Marcus Thompson—still legally a fugitive slave according to Kentucky—enlisted in the 15th USCT, serving until 1866. From 1867 to 1872, he served with the 9th U.S. Cavalry, a famed “Buffalo Soldier” regiment, in Fort Stockton, Texas. Upon his death, he received a military burial in Austin.

SUMMER 2023 21 SOUTHERN ACCENT USAHEC MOUSEION ARCHIVES/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Daniele Celano, a Jefferson Scholars Foundation fellow, is a history Ph.D. candidate at the University of Virginia.

Full Résumé

ACWP-230700-SOUTHERN.indd 21 3/14/23 9:36 AM

SumMer of DisconteNT

By

The detritus of war was evident along the banks of the Mississippi as the 7th Indiana Cavalry made its leisurely descent down the river from Memphis.

On June 17, 1865—with Brig. Gen. Stand Watie’s final formal Confederate surrender less than a week away—the Hoosier State troopers had boarded four steamers headed for Alexandria, La.. It would be a pleasant enough cruise that included a pass of Milliken’s Bend, where Black troops had helped engineer a “bloody” Federal victory on June 6-7, 1863, during the Vicksburg Campaign. “The overflowings of the river were rapidly washing away the earthworks, which the negroes so gallantly defended,” noted 1st Lt. Thomas S. Cogley.

At Natchez, Miss., the convoy stopped for what was intended to be a short respite. Because the pilots were unfamiliar with the river and feared tempting an accident, however, they decided to dock there for the evening. That gave the cavalrymen unexpected free time to write letters back home.

On the move the next morning, they enjoyed

some relief from the long journey’s monotony with numerous glimpses of alligators roaming along the water’s edge. One brazen soldier was surprised to see a bullet he fired from his carbine glance off one large reptile’s tough exterior. And though the act of shooting at alligators eventually grew tiresome, once an order was issued forbidding the routine, it led to an inordinate number of “accidental” weapon discharges.

Most of the men were unaware of their final destination. With the war all but over, they figured they were being sent to muster out of service before being allowed to head home. A collection of troops, most working together for the first time, were joining the 7th Indiana in Alexandria. Among these was the 5th Illinois Cavalry, better known as the “Prairie Boys.”

After departing the Mississippi River northwest of Baton Rouge, the boats steamed up the Red River toward Alexandria, located approximately 260 nautical miles from Memphis. Upon their arrival at the juncture of the two rivers, one of the Prairie Boys had noticed “[d]ull, brownish red, soil-laden water flowed into the

22 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR

As the war ended, Custer and his wife, Libbie, spent time in war-torn central Louisiana. It would be an alarming few months.

LITTLE BIGHORN BATTLEFIELD NATIONAL MONUMENT, NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ACWP-230700-CUSTER.indd 22 3/15/23 8:50 AM

Richard H. Holloway

In Their Element

The Custers pose with Libbie’s attendant, Eliza. While in Alexandria, Eliza convinced the young couple to visit a small group of older former slaves camped behind the local doctor’s house in which they were residing. The Custers were enthused after attending a church sermon conducted by local Blacks.

LITTLE BIGHORN BATTLEFIELD NATIONAL MONUMENT, NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ACWP-230700-CUSTER.indd 23 3/15/23 8:51 AM

Mississippi from the Red River.” During the spring, Red River water levels were normally low, making it hard to navigate, and by the summer of 1865 the river had remained drained and sluggish.

Near Marksville, La., the troopers passed the abandoned earthen works at Fort DeRussy. Then, about 50 miles from their destination, they began to notice that the ground was low, flat, and heavily wooded—but also enveloped by a considerable amount of water, essential for growing sugar and cotton. The heat, though, was oppressive at this time of year, and the heavy tree line cut off any potential breeze to cool the travelers down.

The commander of the group of soldiers assembling in central Louisiana was none other than Maj. Gen. George Armstrong Custer. Accompanied by his young bride, Elizabeth Bacon “Libbie” Custer, the now-famous general had been dispatched to this vicinity by Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan while stationed in Arlington, Va. Rumors were circulating that a Rebel force had pledged to perpetuate the Confederacy in Texas.

At the time the orders were issued, it was speculated that Confederate President Jefferson Davis was on the way to join Major George Kirby and a large force of Southerners in Texas. Some in the North feared the Confederates might even ally themselves with the French in Mexico and reignite the fighting.

Sheridan assigned Custer to pursue and subdue the enemy gathering in the Lone Star State, but he was initially to assemble at Alex-

Lurking Danger

Steamboats prowling tree-lined rivers, many of them filled with soldiers, their equipment, and their animals, were a familiar sight in Louisiana. Such excursions were fraught with hidden water-borne obstacles and alligators.

andria and create an effective fighting force. En route to central Louisiana, the Custers near the end of June had boarded a steamboat in New Orleans. Of their journey, Libbie recalled: “We grew to have an increasing respect for the skill of the [steamboat] pilot, as he steered us around sharp turns, across low water filled with branching upturned tree trunks, and skillfully took a narrow path between the shore and a snag that menacingly ran its black point out of the water.”

As had the troops Custer was about to command, the couple encountered alligators during their voyage, the massive beasts often sunning themselves on sandbars beside the water. Because of the tendency for fired bullets merely to bounce off the creatures’ skin, as the 7th Indiana troopers had already learned, Custer was determined to find a vulnerable spot at which to aim. After a few shots with a rifle borrowed from a steamboat guard, Custer finally succeeded in killing one.

According to Libbie’s attendant, Eliza, the general’s wife had several firsthand opportunities to view alligators at a distance. During the Custers’ boat ride, an unsuspecting African American lad was napping on a sandbar outside

24 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR HERITAGE AUCTIONS, DALLAS, TEXAS HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION/BRIDGEMAN IMAGES; MAP BY AUSTIN STAHL

Alexandria New Orleans

LOUISIANA ACWP-230700-CUSTER.indd 24 3/15/23 8:51 AM

Red River Mississippi River

Alexandria as an alligator crept toward him. Using a loaned carbine, Custer dispatched the animal with a single shot.

On June 23, the 7th Indiana disembarked at a sugar plantation at the edge of Alexandria. The troopers immediately felt the effects of the harsh sun, the open fields offering no shade. Noted Cogley: “Awnings, both for the men and the horses were constructed of poles and brush brought from the woods, which measurably relieved the suffering...”

“The residents had partially rebuilt the town after [Maj. Gen.] A.J. Smith set [it] ablaze when the Federals withdrew in May 1864,” recalled one 5th Illinois trooper. “A few small, one-story cottages replaced the once thriving town....”

“Low, flat countryside bordered Alexandria, and the smell of rank, decomposing vegetation rose from the banks,” wrote another Prairie Boy.

“The hot, tepid air and stagnant water of hundreds of boggy bayous created an oasis for mosquitoes. Clouds of bloodsuckers, including gallinippers [large flying insects with a painful bite] enveloped the men when they landed.”

Libbie Custer seemed even less impressed:

The houses along the Red River were raised from the ground on piles, as the soil was too soft and porous for cellars. Before the fences were destroyed and the place fell into dilapidation, there might have been a lattice around the base of the building, but now it was gone. Though this open space under the house gave vent for what air was stirring, it also offered free circulation to pigs, that ran grunting and squealing back and forth, and even calves sought its grateful shelter from the sun and flies.

Cogley was more sympathetic to the locals’ plight. “Alexandria, before the war was a small city of about five thousand inhabitants,” he noted. “It acquired some historic interest by being given over to the torch, and the greater and best portion of it destroyed by fire, by General [Nathaniel] Banks, when he left….At the time [our] regiment was there, it contained but about five hundred inhabitants. Old chimneys had not yet fallen, and ruined walls marked the site of former business blocks or palatial residences.”

Once the unaffiliated regiments arrived, they were separated into two brigades. The 7th Indiana, 5th Illinois, and 12th Illinois Cavalry comprised the 1st Brigade of Custer’s new division—to be headed by Brig. Gen. George A. Forsyth—and the 1st Iowa

Straight From Libbie’s Heart

Custer’s personal battle flag, sewn by Libbie, who delivered it to him daringly during the March 1865 Battle of Dinwiddie Court House. Bearing it aloft, Custer led a charge in winning the battle. Left behind, it was not with him when he was killed at Little Big Horn.

Cavalry and 2nd Wisconsin Cavalry formed the division’s 2nd Brigade, under Colonel William Thompson’s command.

Also supporting Custer were two Black regiments, the 76th and 80th USCI. While these units were not formally under the command of the cavalry division, they were under Custer’s direction. Each regiment in the mounted brigades were re-fitted with Spencer carbines and new mounts, except the 2nd Wisconsin, which had already been issued them before arriving after winning a shooting contest. Still, the men were lacking in adequate garrison equipment, and had poor clothing issues.

Libbie described the men of her husband’s command as “[t]ired out with the long service, weary with an uncomfortable journey by river from Memphis, sweltering under a Gulf-coast sun, under orders to go farther and farther from home when the war was over, the one desire was, to be mustered out and released from a service that became irksome and baleful when a prospect of crushing the enemy no longer existed.”

Before the troops could settle, Custer issued what turned out to be an extremely unpopular Special Orders No. 2:

Headquarters Cavalry

Alexandria, Louisiana. June 24th, 1865.

Special Orders No. 2.

Numerous complaints having reached these headquarters of depredations having been committed by persons belonging to this command; all officers and soldiers are hereby urged to use every exertion to prevent the committal of acts of lawlessness, which, if permitted to pass unpunished, will bring discredit upon the command. Now that the war is virtually ended, the rebellion put down, and peace about to be restored to our entire country, let not the lustre of the last four years be dimmed by a single act of misconduct toward the persons or property of those with whom we may be brought in contact. In future, and particularly on the march, the utmost care will be exercised to save the inhabitants of the country in which we may be located from any molestation whatever.

As supplies can be obtained from the supply train when needed, there will be no necessity for foraging upon the country.

SUMMER 2023 25 HERITAGE AUCTIONS,

TEXAS HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION/BRIDGEMAN

BY

DALLAS,

IMAGES; MAP

AUSTIN STAHL

ACWP-230700-CUSTER.indd 25 3/15/23 8:51 AM

No foraging parties will be sent out from this command without written permission from these headquarters and then only to obtain fresh beef and grain, for which payment will be made by the chiefs of the proper departments at these headquarters.

Every violation of this order will receive prompt and severe punishment. Owing to the delays of court martials, and their impracticability when the command is unsettled, it is hereby ordered that any enlisted man violating the above order, or committing depredations upon the persons or property of citizens, will have his head shaved, and in addition will receive twenty-five lashes upon his back, well laid on. This punishment will, in all cases, be administered under the supervision of the Provost Marshal of the command, who is charged with the execution of this order so far as it in his power.

Any officer failing to adopt proper steps to restrain his men from violating this order, or fails to report to these headquarters the names of those violating it, will be at once arrested and his name forwarded to the proper authority for prompt and dishonorable dismissal from the army. The commanding General is well aware that the number of those upon whom the enforcement of this order will be necessary will be small, and he trusts that in no case will be necessary.

He is also confident that those who entered the service from proper motives will see the necessity for a strict compliance with the requirements of this order.

Citizens of the surrounding country are earnestly invited to furnish these headquarters any information they may acquire which will lead to the discovery of any parties violating the forgoing order.

Regimental commanders will publish this order to every man in their commands.

By the command of Major General Custer.

The reaction among the command was swift. One of the displeased was 1st Iowa surgeon Charles H. Lothrop, who wrote:

On the promulgation of this order no little indignation was manifested by all the troops, which would be natural among all honorable and high-minded men, who from purely patriotic motives responded to the first call for volunteers to defend and maintain the laws of the country, and endured the privations and vicissitudes incidental to

Apparently Not Enough Power

This sketch, which appeared in the April 30, 1864, edition of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, depicts gunboats and transports in Union Rear Adm. David Dixon Porter’s flotilla in front of Alexandria during Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks’ ill-fated Red River Campaign.

four years’ active warfare, to be thus subjected to eternal disgraces without a shadow of law or precedent; and real citizens, entertaining the most malignant bitterness towards federal soldiers.

Nevertheless, considering the situation facing his men, Custer’s decision had been correct. Indeed, many former Confederate soldiers occupied the surrounding countryside and likely would need only a small provocation to band together and launch attacks on the isolated command. Alexandria’s mayor had surrendered the town only on June 3, mere weeks before Custer’s arrival. Its citizens undoubtedly harbored ill will toward the men in blue, as barely a year had passed since Federal troops had burned their town maliciously on May 13, 1864.

A subsequent wave of desertions was clearly proof Custer had trouble discerning the difference between volunteer soldiers and Regular Army cavalry. In the wake of the order, members of the 5th Illinois began leaving in droves. Although most of these deserters had recently transferred from the 11th Illinois Cavalry, the loss of eight—Joseph Hakin, William H. Barcus, Jesse Cannon, Thomas Ross, John Brown, Thomas W. Wiley, William H. Warren, and Archibald C. Tigner—was somewhat shocking

26 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RICHARD H. HOLLOWAY COLLECTION (2)

ACWP-230700-CUSTER.indd 26 3/15/23 8:52 AM

as they had enlisted at the war’s start in 1861.

Another trooper attempting to flee, William A. Wilson, was caught and court-martialed. Other units also reported serious departures from their command. “On several occasions,” Lieutenant Cogley recalled, “nearly the whole command was called out at night, to prevent the threatened desertions of companies and of a regiment.”

While in Alexandria, 15 members of the Prairie Boys alone deserted, and by the time of their October mustering-out, they would be short 75 troopers. Some dangerous incidents even sprang up during this period.

“The soldiers did not confine their maledictions to the regular officers of command; they openly refused to obey their own officers,” Libbie reported.

“One of the colonels (I am glad I have forgotten his name) made a social call at our house. He was in great perturbation of mind, and evidently terrified, as in the preceding night his dissatisfied soldiers had riddled his tent with bullets, and, but for his ‘Lying low,’ he would have been perforated like a sieve.”

Unfortunately, Custer ended up further exacerbating the friction with his men by directing them to perform menial tasks for his family. In a response to Custer’s report of the strife he was experiencing, Sheridan instructed, “Use such summary measures as you deem proper to overcome the mutinous disposition of the individuals.”

Having become a strict disciplinarian, Custer became enraged when hearing of the trouble in his command. “The conduct of these troops while at Alexandria was infamous, and rendered them a terror to the inhabitants of that locality, and a disgrace to this and any other service,” he would write. “Highway robbery was of frequent occurrence each day. Farmers bringing cotton or other produce to town were permitted to sell it and then robbed in open daylight upon the streets of their town.”

Custer’s command had dissolved into an unruly rabble determined to wreak revenge on the Southern population.

Well after the war, Union 1st Lt. Michael Griffin attempted to explain the problems Custer was having by writing, “[We] had come directly from

the Army of the Potomac.” The inner conflict between Custer and his Western troops was part of a rivalry of who was tougher or better than the other: the hard Western trooper or the apparent dandies from the East. As the war played out, the Army of the Potomac veterans were actually just as tough as their counterparts to the West, having had to fight Lee, Jackson, and Stuart for so long. Dutifully, though, the remaining soldiers who decided to stay endeavored to drill together and become a cohesive unit for the upcoming campaign in Texas.

When it came up in conversation, Custer adopted a soothing demeanor to calm Libbie’s concerns about the openly hostile activities around them. Despite the controversies, Custer and his wife endeavored to make their stay in central Louisiana pleasant. Eliza convinced Libbie to get out and visit the elderly former slaves encamped behind Dr. John Casson’s house in Alexandria where the Custers were staying and where General Banks had lodged in 1864. Eventually, Custer joined in these interactions and provided food for the seniors. They also attended church services there.

“It was at Alexandria that I first visited a negro prayer-meeting,” Libbie recalled. “As we sat on the gallery one evening, we heard the shouting and

Feeling Custer’s Wrath

Privates Joseph Hakin (top) and William A. Wilson (above) of the 5th Illinois Cavalry, both deserted while in Custer’s command. Hakin succeeded in getting away, but Wilson was captured and sentenced to be executed.

SUMMER 2023 27 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RICHARD H. HOLLOWAY COLLECTION (2)

“The soldiers did not confine their maledictions to the regular officers of command; they openly refused to obey their own officers”

ACWP-230700-CUSTER.indd 27 3/15/23 8:52 AM

singing, and quietly crept around to the cabin where the exhorting and groaning were going on. Though they were so poor and helpless, and seemingly without anything to inspire gratitude, evidently there were reasons in their mind for the heart-felt thanks [for the nourishment provided by the Custers] as there was no mistaking the genuineness of feeling when they sang [grateful hymns]. They swayed back and forth as they set about the dimly lighted cabin, clapped their hands spasmodically, and raised their eyes to heaven in moments of absorption.”

The Custers did experience some lighter moments with some of the soldiers not quite as disgruntled as the rest. The 7th Indiana troopers in particular tried to alleviate tensions with their commanding general. After spending long hours in the hot sun drilling, they would often relax by fishing and catching alligators. “Occasionally, a baby alligator from a foot and a half to two feet in length, got on dry land and was taken prisoner by the men,” Cogley wrote.

Aware of Libbie’s fear of the beastly reptiles, Custer proposed to put her at ease by exposing her to one of the smaller ones the Indiana troopers had captured. As Libbie recalled: “[T]he General, thinking to quiet my terror of them by letting me see the reptile ‘close to’ as the children say, took me down to camp, where the delighted soldier told me how he had caught it, holding on to the tail, which is its weapon. The animal was all head and tail; there seemed to be no intermediate anatomy. He flung the latter member at a hat in so vicious and violent a way, that I believed instantly the story, which I had first received with doubt, of his rapping over a puppy and swallowing him before a rescue could come. This pet was in a long tank of water the owner had built, and it gave the soldiers much amusement.” Many times the baby alligators’ parents would come on shore hunting for them, sending the ladies scurrying for safety and the soldiers for their weapons.

Libbie also documented the excursions into the countryside that she and her husband would make to relieve tensions. The heat was still stifling

during daylight so the couple went for evening rides around the area. Libbie’s state of mind eased considerably upon touring the area. “It seemed to me a land of enchantment,” she allowed. “We had never known such luxuriance of vegetation. The valley of the river extended several miles inland, the foliage was varied and abundant, and the sunsets had a deeper, richer colors than any in the North. We sometimes rode for miles along the country roads, between hedges of osage–orange on one side, and a double white rose on the other, growing fifteen feet high. The dew enchanted the fragrance, and a lavish profusion was displayed by nature in that valley, which was a constant delight to us.”

The couple’s explorations brought them to the Louisiana State Seminary and Military Academy, a facility that Libbie noted was still called the “Sherman Institute.”

“General Sherman had been head of this military school before the war, but it was subsequently converted into a hospital,” she elaborated. “It was in a lonely and deserted district, and the great empty stone building, with

Scaled Fear

The sight of a large alligator, even under restraint like this one, often sent the Union officers’ wives scurrying. Libbie Custer was particularly afraid of the beasts, no matter their size and despite her husband’s reassurances.

28 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR OPPOSITE: “TENTING ON THE PLAINS, OR GENERAL CUSTER IN KANSAS AND TEXAS,” BY ELIZABETH B. CUSTER; THIS PAGE: SAM HOUSTON MEMORIAL MUSEUM

ACWP-230700-CUSTER.indd 28 3/15/23 8:52 AM

its turreted corners and modern architecture, seemed utterly incongruous in the wild pine forest that surrounded it.