African Nova Scotians

in the Age of Slavery and Abolition

Black Loyalists, 1783-1792

The aftermath of the American War of Independence brought the Black Loyalists to Nova Scotia. During the war, British authorities in America offered freedom to slaves of rebels who escaped and made their way into British lines. Many enslaved African Americans seized this

|

opportunity to gain their freedom and came over to the British side, as did a much smaller number of already free African Americans. Some of the Black Loyalists provided military service alongside the British Army, while others served in non-military roles. Toward the end of the war most of them converged on New York, which was home to British general headquarters. Three thousand of them sailed to Nova Scotia between April and November 1783, on both Navy vessels and private transports chartered by the British.

|

|

Rose Fortune (ca. 1774-1864)

[1830s?]

|

In addition, a small number of free black people came as Loyalists on an individual basis. By 1784, well over 3000 Black Loyalists had immigrated to Nova Scotia, which included present-day New Brunswick. They came from Virginia, Georgia, South Carolina, New York, and New Jersey, as well as parts of New England. Among them were men and women of accomplishment, such as preacher David George and schoolteacher Catherine Abernathy, and a significant number of skilled labourers and craftsmen. Also among them was the father of Rose Fortune, noted as "Fortune – a free Negro," in the muster roll of Loyalists at Annapolis in June 1784. Other Black Loyalists included the members of the Black Pioneers, the only official black regiment on the British side during the War of Independence. There were also a number of ship pilots, such as London and James Jackson, who had been employed by the British during the war.

The Black Loyalists founded settlements throughout Nova Scotia. The largest was at Birchtown, near Shelburne, with an initial population of about 1500. The people of Birchtown earned their living in the fishery, cutting wood, clearing land, and hunting, and as domestic servants and day labourers. Other settlements were Brindley (Brinley) Town (near Digby), Preston, Birchtown (Guysborough County), Negro Line (now Southville, Digby County), and Birchtown (Princedale-Virginia East-Graywood area, Annapolis County). A group of about 170 settled at Old Tracadie Road (Guysborough County).

|

The Black Loyalists were part of a larger wave of Loyalist immigration which numbered around 30,000 people. The sudden influx of so many people placed a strain on the resources of the Nova Scotia government. The Black Loyalists encountered unfair and unequal treatment. They were given much smaller plots of land and fewer provisions than white settlers. Indeed, many did not receive any land, and some received no provisions. Black labourers were paid lower wages than white labourers for the same work. In 1784, local white labourers and disbanded soldiers drove black people out of Shelburne because they blamed them for low wages and unemployment. In addition, black people were faced with discriminatory local bylaws that penalized them for ‘offences’ such as dancing or loitering.

Despite the arrival of over 3000 free black people, the Loyalist influx also brought an estimated 2500 slaves to Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. They served their Loyalist owners as domestics, labourers and farmhands. In the summer of 1784, Lieutenant Colonel Morse CE reported in his return of disbanded troops and Loyalists that there were 1232 slaves in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. However, he excluded Shelburne, where the slaves were most numerous, as well as other places such as Halifax and Cape Breton, where slaves of Loyalists were also to be found. The number of slaves in Shelburne stood at 1269, as shown by a report on the number of persons receiving government rations there on 8 January 1784. The combined total of the two reports is 2500, double the number generally cited.

|

By 1790, many Black Loyalists had become dissatisfied with conditions in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. About 1200 of them accepted the offer of the Sierra Leone Company (a British anti-slavery organization) to resettle in Sierra Leone, on the Atlantic coast of west Africa. Approximately 1000 Black Loyalists from Nova Scotia left. Most came from Birchtown (Shelburne County), Preston and vicinity, Digby, and Annapolis. Nearly every black resident of Preston and Brinley Town left. The emigrants sailed from Halifax for Sierra Leone on 15 January 1792. Among them were community leaders such as David George (Shelburne), Boston King (Preston), and Joseph Leonard (Brinley Town). Stephen Skinner, local government agent at Shelburne, listed the occupations of the emigrants as farmers, skilled tradesmen, and soldiers. Their possessions included tools, a few muskets, and some tables, beds, chests and spinning wheels. Some families, including David George’s, took their dogs with them.

The majority of free African Nova Scotians remained in the province. Among them were those in Halifax, those in the Black Pioneers and those skilled as ship pilots. The free black people in Guysborough also remained, probably due to the fact that they were not properly informed of the Sierra Leone Company’s offer. Thomas Brownspriggs (Tracadie) and Stephen Blucke (Birchtown) were two teachers and community leaders who stayed. Prior to the exodus, Blucke warned Lieutenant Governor Parr against the expedition to Sierra Leone. His petition, also signed by 50 other free black people remaining in Shelburne County, forecast that those who went to Sierra Leone would face "their utter annihilation." Contemporary white observers noted the economic cost of the exodus. Stephen Skinner wrote that the settlement had been "deprived of upwards of five hundred good and efficient citizens...." Gideon White of Shelburne described it as "a serious loss."

|

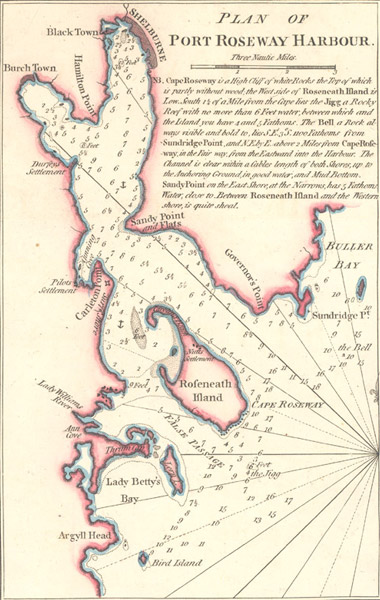

Plan of Port Roseway Harbour published London 12 July 1798

A New Chart of the Coast of Nova Scotia...by Captain Holland

"A black wood cutter at Shelburne, Nova Scotia" 1788

National Archives of Canada C-040162

|

The efforts of free African Nova Scotians to obtain land grants, to improve their allotments and to establish their own communities had a considerable impact. Interaction between free and enslaved African Nova Scotians must have greatly influenced the attitudes and expectations of the slaves. Slaves escaped in increasing numbers, as they now had the opportunity to disappear into the free black population.

click to view all items for this chapter

|

print version print version

en français en français

|