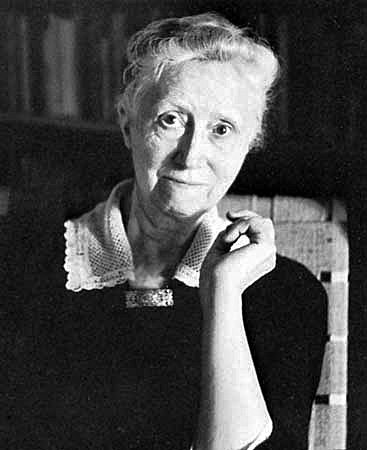

Elizabeth Bishop ’1934

The only child of William T. Bishop and Gertrude May Bulmer Bishop and born in Worcester, Massachusetts, on February 8, 1911, Elizabeth Bishop suffered a difficult childhood. Her father died when she was eight months old, and her mother was institutionalized in 1916 with mental illness. When her mother died in May 1934, as Bishop was graduating from Vassar, she mentioned the death only as an aside to her close friend Frani Blough ‘34: “I guess I should tell you that mother died a week ago today. After eighteen years of course it is the happiest thing that could have happened.” Mother and daughter had never spoken after Gertrude entered the asylum.

After her mother’s institutionalization, Bishop lived with her grandparents in Great Village, Nova Scotia, and, returning to Massachusetts in 1918, with her mother’s older sister, Maud Shepherdson and her husband George.

“Always a sort of guest” in her aunt’s house, Bishop said she and Maud “loved each other and told each other everything.” Illnesses as a child—notably chronic asthma—interrupted her early education, and she spent her high school years at Walnut Hill School in Natick, Massachusetts. At Walnut Hill, Bishop met her lifelong friends Frani Blough, Barbara Chesney and Rhoda Wheeler, and she published her first poems in the school magazine.

Having studied music at Walnut Hill, Bishop entered Vassar in the fall of 1930 with the hope of perhaps becoming a composer. She sang in the choir during her freshman and sophomore years, but music students were required to perform in public once a month, and “this terrified me,” she told Elizabeth Spires ’74. “I really was sick. So I played once and then I gave up the piano because I couldn’t bear it…. Then the next year I switched to English.”

Eleanor Clark ’34, a close friend at Vassar—and herself a successful writer in later years—recalled that she and Bishop were “very untypical American college freshmen…bored and unhappy and not wanting to do the things that seemed to be what other people were taking pleasure in.” Bishop missed the intimacy of Walnut Hill, and the size of Vassar overwhelmed her. She lived in a “great big corner room” on the top floor of Cushing House, she told Spires. “I had a roommate who I never wanted to have” who furnished the room with “Scotty dogs–pillows, pictures, engravings, and photographs.” Bishop was undeniably also not a very good roommate. Believing, for instance, that poems came more easily from one’s dreams, she kept a pot of pungent Roquefort cheese in the bottom of her bookcase. She believed, she admitted, “if you ate a lot of awful cheese at bedtime you’d have interesting dreams.”

Clark also recalled a winter night in their freshman year when the two decided to run away, not for “any permanence, but to get out of there.” Taking a southbound train, they headed for Clark’s vacant home in Litchfield County, Connecticut. The train stopped at Stamford, in Fairfield County, forcing the two women to start to hitchhike some 70 miles in “almost a blizzard” at two in the morning. The only car to stop for them held two police officers, who brought them to the station. The police, Clark recalled, “didn’t believe for a minute that we were college girls,” instead thinking them to be prostitutes. Eventually, Clark’s mother drove them back to Vassar after the officers, finding “Greek notes…a magazine…called Breezy Stories…and The Imitation of Christ” in the pockets of Bishop’s pea jacket, “decided it had to be something beyond the usual.”

Recalling her peculiar sense of adventure, Bishop told in an interview of spending a night in a tree outside Cushing House: “It was me, me and a friend whose name I can’t remember. I used to be a great tree climber. Oh, we probably gave up about three in the morning.” Other vices, more common to a college student’s life, marked Bishop’s. In 1934, she wrote to Blough, “I have eight empty bottles in my lowest…drawers and they are accumulating fast…we are now in the season where one stays up until 1:30 as a matter of course.” Rather aloof from the campus social life, Bishop spent many weekends in New York City; she later noted that the train trips along the Hudson were some of her most vivid memories of college.

As an English major, Bishop took half her courses in that field: 16th and 17th century poetry; Shakespeare and other Renaissance drama; contemporary prose fiction; literary theory; American literature; and modern poetry. She studied four years of Greek as well as Latin, chemistry and music. She was an uneven student, earning mostly A’s in her English courses but occasionally dropping to a C and fluctuating between an A and a D in Greek. In an interview with Eileen McMahon in 1978, Bishop recalled usually feeling distracted in class, but she remembered working tirelessly on Latin: “I had an excellent teacher while I was at Vassar. I remember sitting for a couple years on Monday mornings and writing Latin prose from English prose… I do think that Latin is probably the best writing exercise I can think of.” For her senior project, Bishop, with impressive determination, translated Aristophanes’s The Birds in its entirety.

As she had at Walnut Hill, Bishop had often criticized teachers and courses at Vassar. In October 1933, the formidable Vassar English Professor Helen Lockwood fell under her scrutiny. “Lord that woman is a fool,” she wrote to Frani. “Her latest assignment is a list of such names as: ‘The 100 of America,’ ‘The College Boy,’ ‘The Business Man,’ ‘His Wife’…. We’re supposed to list all the typical things about them—all the magazine clichés I guess—and then sit around.” In January 1934, she criticized a speech by President Henry Noble MacCracken in which he encouraged the students to “make new friends, read new books, and explore the Museum…. Having five papers due—the inevitable number—I rather resented it.”

Bishop’s teachers mirrored her opinions, often commenting on her aloofness and detachment in class. Her freshman English instructor, Barbara Swain, wrote of Bishop in a letter to Anne Stevenson in 1963, “My acquaintance with Elizabeth Bishop was purely a classroom one, and very distant at that, since she was an enormously cagey girl who looked at authorities with a suspicious eye and was quite capable of attending to her own education anyway.”

Bishop chose her campus alliances carefully. For two years, she acted in and wrote for the “hall” plays, and in November of 1932, she joined the editorial staff of The Miscellany News, writing the venerable and widely read humor column, “Campus Chat,” defined by her Misc. friend, Harriet Tompkins ’35, as a “humorous commentary on the current campus scene—bits of verse, take-offs, parodies and jokes.” Bishop usually wrote during staff meetings “by herself alone over in a corner of the room.” Other times, she told Eileen McMahon, she deserted the editorial staff to sit at “The Popover Shop” across the street. “There I would sit and write these awful brief humorous bits, or editorials, or poems—funny poems.” Bishop also told Elizabeth Spires about these withdrawals: “On the newspaper board they used to sit and talk about how they could get published and so on and so on. I’d just hold my tongue. I was embarrassed by it. And still am. There’s nothing more embarrassing than being a poet, really.”

Despite this reticence, in 1933 Bishop,—along with Frani Blough, Eleanor Clark ’34, Margaret Miller ’34, Mary McCarthy ’33, and Clark’s sister, Eunice’33—started a literary magazine called Con Spirito. The campus literary magazine, the Vassar Review, seemed to them not just “dull and old-fashioned”; it had a habit of turning down submissions from this circle of friends. Her literary crew, Bishop said, was “rather put out” by these dismissals because “we thought we were good.” The friends responded, using the musical term, Con Spirito, to suggest both creating with new life and vigor and doing it conspiratorially.

The editors of the anonymously published journal held surreptitious meetings in “Signor Bruno’s,” a nearby speakeasy “where,” McCarthy recalled, “you got a sort of dago red in thick white cups.” The college physician later analyzed this wine and found it contained 50 percent alcohol, although Bishop doubted this was accurate. In an October 1933 letter to Blough, announcing that the last issue would come out soon, Bishop felt “pretty encouraged—there’s a lot of mediocre verse, of course, but there are really some quite interesting things in the first one.”

At Vassar in May 1933 for the premiere of his first verse drama, Sweeney Agonistes, T.S. Eliot read and spoke about his poetry. Eunice Clark, as editor-in-chief of The Miscellany News, assigned Bishop to interview the famous author. She recalled this interview in the conversation with McMahon, “I was absolutely scared to death—just sick… I had on a summer suit that I wore with spectator sport shoes… At the time the honorable guests were put up in Andrew [sic] Vassar’s suite. It was full of wonderful old Victorian stuff. Eliot and I sat on a horse hair sofa. I remember my legs were too short and I kept sliding off the sofa. He looked exhausted and sat mopping his brow. He had given a talk that afternoon…. I think he finally asked me if I would mind if he undid his tie, which for Eliot was rather like taking off all his clothes. I can’t say I ever felt at ease, but he was extremely nice.”

Most of the resulting Miscellany article, “Eliot Favors Short-Lived Spontaneous Publications,” focused, not surprisingly, on college literary magazines. Bishop quoted Eliot as saying a magazine was “more interesting and had more character the fewer the editors and the fewer the contributors.” “Actual contributors are more trouble than they are worth, Mr. Eliot thinks; the editors themselves should do all the writing. Nor should the college magazine ever attempt to improve upon its own possibilities by getting its superiors or elders to help it along.”

Con Spirito was short-lived, producing only three issues before combining with the Vassar Review to create a unified editorial board. Bishop recounted the merging to Blough in December 1933, “‘Con Spirito after another very poor number decided (1) to die, then (2) to join the Review, which seemed to show signs of coming to life and wanted us. Eleanor Clark and Margaret [Miller ‘34], the only people who had any census points[i], were put on the Review board, and things looked very hopeful. But they’ve been having a terrible time, it seems, and the first joint number promises to be awful.” Parodying Spenser, Bishop wrote a poem ‘celebrating the match.”

“Hymen, Hymen, Hymenaus,

Twice the brains and half the spaeus.

Con Spirito and the Review

Think one can live as cheap as two.

Literature had reached a deadlock

Settled now by holy wedlock,

And sterility is fled…

Bless the happy marriage bed.”

Eventually, the two publications resolved their differences and published cooperatively. Bishop could write freely and became the journal’s most consistent contributor, honing her skills as a poet, editor and writer and gaining an intellectual reputation on campus. Nominated as the “Class Aesthete,” she was caricatured in the Review, along with two other students, as “the Higher Types.”

In their senior year, Bishop and Margaret Miller edited Vassar’s yearbook, the Vassarion, and soon Bishop wrote to Blough declaring, “The Vassarion is getting the better of me.” Some girls refused to have their photos taken while others “got into a state and tore them all up.” Harriet Tompkins ‘35, knowing Bishop from the Miscellany News, did her bit by having dinner with a man from Ligget’s Drug Store.

Recounting Tompkins’s sacrificial act in a letter to Frani, Bishop reported her own solicitation before a group of alumnae. “Didn’t you once have to make a speech at Alumnae House? Well, I did last Saturday, a sort of advertising turn in between courses of a luncheon for the Vassarion. I was introduced as Eleanor Bishop and people kept shouting ‘Louder’ and I think I got four subscriptions out of it. So I guess I’m not much of a public speaker. However, the Vassarion is coming pretty well. It’s almost done, and Harriet just went out to dinner with a man from Liggett’s drugstore and go a full-page ad. It’s a very demoralizing piece of work.”

Although Bishop recalled classmates’ assurances that the yearbook was “the nuts” when it appeared in May, mistakes and careless presswork left her in “a state of rage and despair.” In the book’s introduction, Bishop and Miller say they wanted to connect their classmates with the classes of past years. Surprisingly old-fashioned in appearance, with a cover of maroon velvet, the volume’s pages were filled with photographs of Vassar from the late nineteenth century.

When asked, years later, by her friend and correspondent, Ashley Brown, whether she considered pursuing a career in poetry while at Vassar, Bishop responded, “I never thought much about it.” If anything, Bishop’s thoughts about life after college focused on studying medicine, a possibility she harbored well after leaving Vassar. During her junior and senior years, however, Bishop submitted work to both competitions and publishers. In 1933, she won honorable mention in a national undergraduate writing competition sponsored by Lincoln Kirstein’s New York journal, Hound and Horn. In January 1934, Bishop told Blough that she had received a check for $26.18 from The Magazine, a California literary magazine, for “Then Came the Poor,” a short story that had appeared in Con Spirito the year before.

She also experienced a taste of the fickle publishing world. Two months later, Dudley Fitts, a colleague of Kirstein’s who had solicited some work, rejected the poems, she told Frani, because they were “’too mannered,’ ‘too clever,’ and also I remind him of [Gerard Manley] Hopkins and—of all people—[Thomas] Hardy (Having read practically none of Hardy’s poems, and those I have read being either descriptions of funerals or the complaints of seduced milkmaids in Devonshire dialect, I’m pretty mad.) I know they’re not wonderful poems but even so I think that to try to develop a name/manner of one’s own, to say the most difficult thing, and to be funny if possible (which is what he means by ‘too clever,’ I imagine) is more to one’s credit than to go on the way all the young H. & H. poets do with ‘One sweetly solemn thought’ coming to them o’er and o’er. Oh Hell-I thought I might get myself a new hat with the money at least.” One of the rejected poems, “Hymn to the Virgin,” appeared in The Magazine a month after Bishop’s short story.

In her senior year, Bishop felt the apprehension and restlessness common to most students before graduation. “This awful cloud,” she wrote to Blough in December of that year, “that hangs over senior year—thinking all the time where I shall be next year this time for heaven’s sake.” Bishop’s postgraduate thoughts ranged from going to Boston to live with Frani Blough, or traveling cross country, to moving to New York City. Despite taking one only science class at Vassar, she continued to think of attending medical school and later recalled filling out almost all the papers for the application. Her indecisiveness, however, shifted after meeting the poet Marianne Moore during the spring of her senior year.

One day, looking in the Library for Moore’s Observations (1924), Bishop asked the Vassar librarian, Fanny Borden, why the book wasn’t in the collection. In an interview with George Starbuck, Bishop remembered the ensuing conversation: “‘Are you interested in her poetry?’ (She spoke so softly you could barely hear her) and I said ‘Yes, very much.’ And she said, ‘I’ve known her since she was a small child. Would you like to meet her?’” In a letter to Blough in March 1934, Bishop recounted her discovery: “I found out last week to my great surprise that Miss Borden…is a friend of Marianne Moore.

I started a sort of paper on her and Miss Borden has the only copies of her books at the college…. She first met M. M. when she was a little girl and was so fascinated with her that she’s kept knowing her ever since. She had brilliant red hair and called everyone she knew by the names of animals. Now she lives in Brooklyn, is quite poor, I gather, and has to devote herself entirely to taking care of her mother. She can’t even go out for an hour, Miss Borden says. I want very much to go see her. She can talk faster and use longer words than anyone in New York.”

Moore did not like meeting students from Vassar. She told Bishop to meet her on the right-hand bench outside the Reading Room at the New York Public Library, because it was “a safe place to meet people, since she could get rid of them quickly.” “Something worked—a stroke of luck,” Bishop recalled, and the two ended up getting along very well. Two weeks later Bishop took Moore to the circus—a passion of Moore’s unknown to Bishop—thus sealing their friendship. They exchanged letters for the rest of Bishop’s time at Vassar, developing a friendship—and a mentorship—that would last until Moore’s death in 1972.

Deciding to pursue her poetry after graduation, Bishop moved to New York City because, as she told Blough in a letter, “there’ll be more chances for reviewing.” Mary McCarthy located her an apartment in Greenwich Village where Bishop typed poems to send to magazines, while searching for other employment. In April 1935, with a trip to Europe in mind, Bishop began a tutorial at Columbia University in reading and translating French. After she visited Harriet Tompkins at Vassar that spring, the two decided to travel to France and meet with Louise Crane, ‘36 who was there with her mother. Bishop stayed in Europe, traveling extensively with Crane in Morocco and Spain, until June of 1936.

Traveling put immediate literary aspirations on hold, but Bishop’s connection with Moore kept the career a possibility. After four months of friendship, Bishop told Moore she was interested in becoming a poet. Moore responnded with steady encouragement to write, submit and publish. A nationally known poet and former editor of the influential literary journal, The Dial, Moore had many connections that helped Bishop, and she recommended Bishop to many editors and publishers. In late 1934, Edward Aswell of Harper and Brothers asked Moore about Bishop, “Horace Gregory told me the other day about a young poet named Elizabeth Bishop whose work has impressed him greatly…. I gathered from him that Miss Bishop is now abroad but that you are in touch with her and would know whether she is really ready to publish a book. If she is, I should like very much to have a look at her collected poems.” Not feeling ready to publish a book Bishop declined this and other such offers during these first years after Vassar.

The poet and her young protégé continued to correspond while Bishop was abroad, with Moore evaluating and encouraging Bishop’s writing. In spring 1936, Bishop published “The Man-Moth” in the spring edition of the English journal, Life and Letters To-Day. Moore responded a few months later with her thoughts: “The poem by you in Life and Letters Today takes me by surprise. It is difficult to sustain atmosphere such as you have there. But you do sustain it and one’s feeling that the treatment is right is corroborated by one’s sense of indigenousness, and of moderate key.”

Bishop’s breakthrough came in 1946, when Moore suggested her for the Houghton Mifflin Prize for Poetry, which Bishop won over some 800 other entries. Her first book of poetry, North and South, was also published that year. In 1947, she won a Guggenheim Fellowship and two years later, became Poet Laureate of the United States. In Elizabeth Bishop: Life and Memory of It (1993), Brett Candlish Millier, concludes that “Marianne Moore was without a doubt the most important single influence on Elizabeth Bishop’s poetic practice and career.” Miller also notes Moore’s succinct assessment of her mentorship, quoting from a letter from 1936 to Edward Aswell of Harper and Brothers: “In her outlook on life she is unusual, and taking an interest in her progress does not amount to having assumed a gigantic burden.”

Bishop’s inquisitive restlessness expressed itself time and again in the years after she left Vassar. Going, again with Louise Crane, to Florida in the winter of 1937, she became enchanted with Key West, where she eventually made a home to which she would return, from time to time, over the next decade.

On what was to be a trip around the world by freighter in 1951, she was so struck by the first port of call, in Brazil, and by a reunion with an earlier acquaintance, Lota de Macedo Soares, that the trip ended there, and the resulting residence in Brazil and an intimate friendship with Lota prolonged her stay for some 17 years.

Her writings reflected more and more the influences of both Brazil and Lota. Writing to her friend and colleague Robert Lowel, she said “probably what I’m up to is creating a sort of de luxe Nova Scotia all over again in Brazil. And now, I’m my own grandmother.” Bishop returned to New York City in 1967, where Lota, following her, committed suicide.

Bishop’s success grew as the years passed; she won the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry in 1956, the National Book Award in 1970 and the Nation Book Critics Circle Award in 1977. In 1976, she became the first woman to win the $50,000 Books Abroad-Neustadt Prize for Literature, and she remains the only American recipient of this international honor, widely considered “the American Nobel.” She was elected to the National Academy of Arts and Letters in 1976.

Bishop returned to Vassar several times over the years for readings and interviews. In 1971, She read from her works at Vassar during the AAAVC Centennial Celebration and, at 68, she returned on May 2, 1979 “for an encore performance.” In October of that year, Bishop died, of a brain aneurism, in Boston, Massachusetts.

From 1969 until her death, Elizabeth Bishop served as poet-in-residence at Harvard, teaching in much the same uncharacteristic and unconventional manner she practiced as a student. One student of hers, Dana Gioia, recalled learning, not through course work or lecture, but through Bishop’s daily interactions, habits, and speech that “one did not interpret poetry; one experienced it.”

In December 1981, Vassar purchased Bishop’s personal collection of papers which included correspondence, notebooks and diaries, printed matter, photographs, artwork as well as hundreds of letters from Bishop’s friends and fellow poets and 3,500 pages of manuscript. Since this acquisition, more than 30 significant additions have joined the collection, providing, according to the collection’s curator, “a starting point and the most significant resource for anyone interested in Bishop.”

Footnotes

[1] In order to “restrict…non-academic activities, but also to distribute the honors and duties of college officers among a larger number of girls,” participation in extra-curricular activities carried variable “census points,” as determined by the Census Bureau. Each student was limited to 10 census points per semester.

Related Articles

Sources

Fountain, Gary. Remembering Elizabeth Bishop: An Oral Biography, The University of Massachusetts Press 1994.

George Montiero, ed., Conversations with Elizabeth Bishop, University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, 1996.

Giroux, Robert (ed.), One Art: Letters, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 1994.

Millier, Brett Candlish, Elizabeth Bishop: Life and the Memory of It, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles,California. 1993.

“News Notice,” The Vassar Miscellany News, Volume XVII, Number 16, 23 November 1932

“Eliot Favors Short-Lived Spontaneous Publications,” The Vassar Miscellany News, Volume XVII, Number 46, 10 May 1933

“Elizabeth Bishop to Read From Her Works,” The Vassar Miscellany News, Volume LXVIII, Number 11, 27 April 1979

“Elizabeth Bishop ’34 Starts Literary Career at Vassar,” The Vassar Miscellany News, Volume CXLIV, Number 12, 18 January 2011

Bronski, Peter, “Celebrating Elizabeth Bishop, Vassar Quarterly, vol. 107, no. 1, Winter 2011

Vassar College Special Collections Library:

Box 13 – Letters from Marianne Moore; Folders 13.1and 13.2, 1935–1936

Box 34 – Letters to Frani Blough Muser; Folders 34.1, 34.2 and 34.3, 1929–1934

ET, 2015