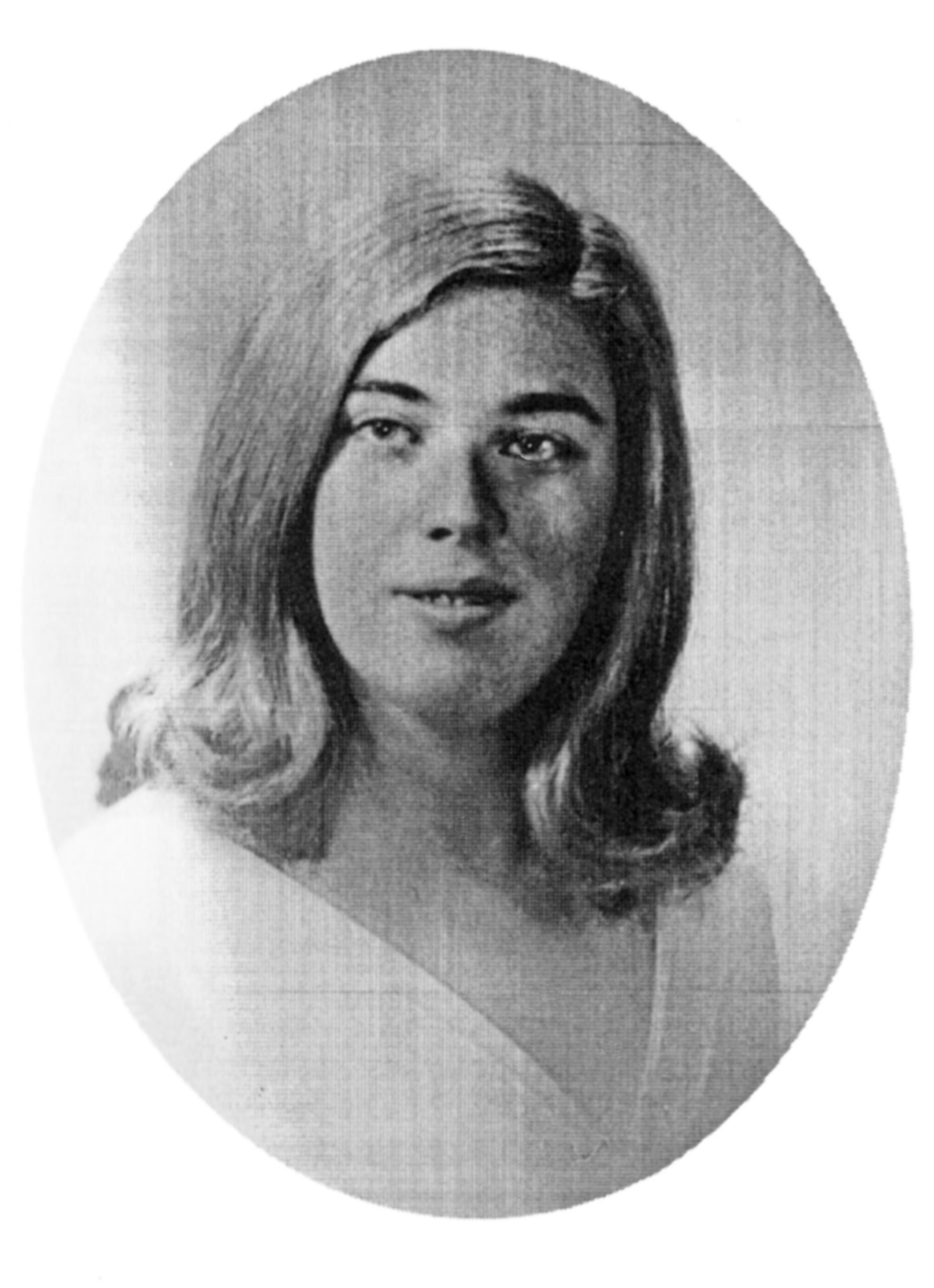

Alison Bernstein ’1969

A woman who came of age in the turbulent 1960s, Alison Bernstein was very much a product of her time—a woman who recognized the world’s problems and actively sought to fix them. Bernstein used her keen intellect and the tools she acquired in her time at Vassar to help others. From her time working in the Student Government Association (SGA), where she spoke out for the rights and privileges of Vassar women, through her time as the youngest trustee in Vassar history, to her far-reaching time at the Ford Foundation, Bernstein stood up for the marginalized. Bernstein was a woman of action who worked within the system and strove for tangible successes.

Alison Ricky Bernstein was born into a Russian Jewish family on June 8, 1947, in Brooklyn. Her father, Robert Bernstein, wrote comic books, contributing to issues of Batman, Superman and Archie. Bernstein spent much of her youth in Roslyn Heights on Long Island, where she attended the Wheatley School in Old Westbury. She matriculated at Vassar in the fall of 1965 as the Vietnam War was escalating abroad and the Civil Rights Movement was reaching a fever pitch at home. Serving as president of the freshman class while also contributing heavily to campus political conversation, Bernstein quickly left her mark on campus. She was an active member of the Vassar Debate Club, Student Judicial Committee, and the Young Democrats; she composed music and played the piano. A pupil of the historian of American culture, Bernstein majored in history while also taking multiple classes in religion, sociology, geology and drama. Bernstein’s education continued outside the college, as she received real-world experience interning with Arizona Representative Morris K. Udall in the summer of 1968. Throughout her time at Vassar, Bernstein’s peers recognized her as a strong and intelligent presence always sporting a lively sense of humor. Active from her freshman year in campus politics, she was praised for the music she supplied in 1967 for the Sophomore Play and, later, for her piano music at the candlelight dinner of the Junior Prom.Upon graduating, she was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and received the Bertha Crosley Ball Award given “to the outstanding girl of each senior class who, in her thinking and planning for life, most nearly approaches the best American ideals.”Bernstein probably left her greatest mark on the campus as a student in her role as president of the SGA. She ran unopposed and came into office with a sweeping liberal agenda, immediately establishing a new student government constitution in order to better define the SGA’s role. She proposed an end to parietal rules and ultimately wanted, she said, to “give students primary responsibility for governing their own lives.” In her new plan, all students, except first semester freshman, would have unlimited sign-outs and night leaves, and car privileges would be given to sophomores and juniors along with other socially liberating changes. A leader at the various conferences with trustees and the administration on campus and at Lake Minnewaska, Bernstein played a vital role in the lead up to co-education. She made her role as SGA president a position that affected the lives of Vassar students present and future.

Following graduation, Alison Bernstein made the abrupt transition from active pupil to member of the Board of Trustees. In October of 1969 she got a surprise phone call from the board’s new chairman, Elizabeth Purcell’31, who asked if she would fill the final three and half years of the unexpired term of another trustee who resigned earlier in the year. The board sought a “young trustee” who might be able to bridge the gap between them and unruly youth. The call shocked Bernstein who immediately, she recalled, “started screaming.” Her mother came sprinting into the room thinking “it was my boyfriend asking me to marry him.” Alison was thrilled by the opportunity but had to confer with her father first who said, “It’s ok with me as long as I don’t have to pay for a building.” Thus the 22-year-old Russian Jewish girl who could often be seen donning “Levis, sweater, floppy brown felt hat, long blonde hair streaming past her shoulders.” would be a trustee of the school from which she had just graduated. President Alan Simpson, who probably suggested it, said of the appointment, “If anyone can mediate between hairy youth and hoary age, it is Alison Bernstein. She is a brave, bright, loyal and lovable spirit.” Bernstein faced a vexing tenure as a trustee, as she was a monetary, political and social outsider. Most members of the board were senior members of corporations or banks or Vassar graduates whose husbands careered such titles who had resources and experiences that Bernstein did not possess. Although her father did not have to “pay for a building,” Alison did have to buy an entirely different wardrobe for her various trustee engagements. While most board colleagues spent the night before a meeting at Alumni House, Bernstein slept in a friend’s dorm room. Although she was certainly not “the flaming revolutionary radical type” she was clearly the farthest left on the board politically. While working on the committees of undergraduate life, women, minority students and of faculty and studies, she was “a supporter of the minority opinion.” This dissimilarity manifested itself most profoundly during a sit-in led by African American students that took place during her first board meeting. Bernstein provided the students with food and made sure the trustees did not contact the local authorities. She even convinced one of her colleagues to call Governor Nelson Rockefeller to make sure the local sheriff did not cause any trouble. During her time as trustee, Bernstein gained an “opportunity…to see the power structure” that led her to conclude that the system was “not malevolent,” just often misguided. This revelation served as a basis for her life’s work.

Along with her work as a trustee, Alison Bernstein pursued graduate study at Columbia University on a Danforth Scholarship, a grant awarded to students “with a passion for helping others.” An unexpected result of being a young trustee occurred when her current graduate professor was employed as a visiting professor by the college of which his student was a trustee. She received her M.A in history in 1970 with a thesis on “American Indians and the New Deal.” Later that year Bernstein worked at Staten Island Community College where she recalled teaching “Introduction to American History in a trailer in a parking lot” three times a week at 8:40 A.M for four years. Enabled by both her work as a trustee and the hands-on experience teaching, in 1974 Bernstein took a job in Washington D. C. with the federal Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education. In 1979 she and the fund’s director, Virginia B. Smith— Vassar’s president between 1971 and 1986,—published The Impersonal Campus,Options for Reorganizing Colleges to Increase Student Involvement, Learning, and Development. Alison Bernstein’s drive to improve educational opportunities for students led her to the Ford Foundation in 1982, where she started as a program officer determining if proposed programs were worthy of financing. Bernstein eventually became, as she put it, “VP overseeing other grantmakers for the foundation’s Education, Creativity and Free Expression Program.” At the Ford Foundation she distributed approximately $400 million a year to charitable causes around the world. Alison became an icon in the philanthropic community, a leader in higher education and an international champion of justice. Once again she used the tools she learned at Vassar along with her drive and gifts as a creative thinker to enact change and make a difference for a large number of people.

In addition to her tireless work at the Ford Foundation, Bernstein received her Ph.D. in history in 1985 with her dissertation focusing on the experience of Native Americans during World War II that later became her 1991 book American Indians and World War II: Towards a New Era in Indian Affairs. She took a short hiatus from the Ford Foundation in 1990 to become Associate Dean at Princeton, only to return two years later as head of the Education and Culture Program. She continued at the Ford Foundation for the next 18 years, finally stepping away from the foundation in 2010. This move did not signal retirement, however, as Bernstein continued to pursue the goals that drove her since her days at Vassar. In 2011 she became the Director of the Institute for Women’s Leadership at Rutgers University and further pioneered the rights of women in academia, raising more than $2 million to fund a chair in media, culture and feminist studies at the college in Gloria Steinem’s name. Alison Bernstein died on June 30, 2016, from endometrial cancer. She was survived by her partner Johanna Schoen and her two daughters.

Sources

Vassar College Special Collections Library, Alison Bernstein Files

“Remembering Alison Berstein,” https://www.fordfoundation.org/ideas/equals-change-blog/posts/remembering-alison-bernstein/

“Alison Bernstein, Educator and Ford Foundation Executive, Dies at 69, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/10/arts/international/alison-bernstein-educator-and-ford-foundation-executive-dies-at-69.html

“Sophomore Play: VC Rediscovers Revolution,” The Miscellany News, Vol. LI, No. 19, March 15, 1967.

“Reports Probe Role and Future of College; Innovations Established….Quo Vadis Vassar?” The Miscellany News, Vol. LIII, No. 1, August 28, 1968.

“Alison Bernstein ’68 Named as Trustee,” The Miscellany News, Vol. LIV, NO. 5, October 31, 1969.

“An Indelible Idealist,” Vassar Quarterly,Vol. 94, No. 4, Fall, 1998.