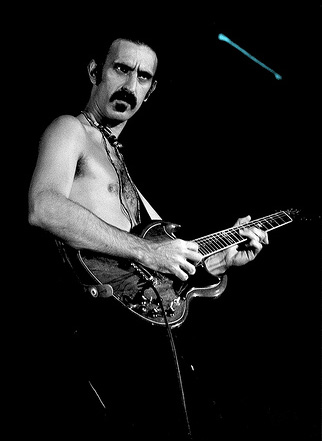

Frank Zappa

Frank Zappa |

|---|

Frank Vincent Zappa[1] (December 21, 1940 – December 4, 1993) was an American composer, musician, and film director. In a career spanning more than 30 years, Zappa established himself as a prolific and highly distinctive composer, electric guitar player and band leader. He worked in almost every musical genre and wrote music for rock bands, jazz ensembles, synthesizers and symphony orchestra, as well as musique concrète works constructed from pre-recorded, synthesized or sampled sources. In addition to his music recordings, he created feature-length and short films, music videos, and album covers.

Although he only occasionally achieved major commercial success, he maintained a highly productive career that encompassed composing, recording, touring, producing and merchandising his own and others' music. Zappa self-produced almost every one of the more than sixty albums he released with the Mothers of Invention or as a solo artist. He received multiple Grammy nominations and won for Best Rock Instrumental Performance in 1988 for the album Jazz from Hell.[2] Zappa was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1995, and received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1997. In 2005, his 1968 album with the Mothers of Invention, We're Only in It for the Money, was inducted into the United States National Recording Preservation Board's National Recording Registry. The same year, Rolling Stone magazine ranked him #71 on its list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time.[3] In 2007, his birthtown Baltimore declared August 9 official "Frank Zappa Day" in his honor.[4]

Politically, Zappa was a self-proclaimed "practical conservative", an avowed supporter of capitalism and independent business.[5] He was also a strident critic of mainstream education and organized religion.[6] Zappa was a forthright and passionate advocate for freedom of speech and the abolition of censorship, and his work embodied his skeptical view of established political processes and structures.[7] Although many assumed that he used drugs like many musicians of the time, Zappa strongly opposed recreational drug use.[8] Zappa was married to Kathryn J. "Kay" Sherman (1960–1964; no children), and then in 1967 to Adelaide Gail Sloatman, with whom he remained until his death in December 1993 of prostate cancer. They had four children: Moon Unit, Dweezil, Ahmet Emuukha Rodan and Diva Thin Muffin Pigeen. Gail Zappa handles the businesses of her late husband under the company name the Zappa Family Trust.

Biography

Early life and influences

Frank Zappa was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on December 21, 1940 to Francis Zappa (born in Partinico, Sicily) who was of Greek-Arab descent, and Rose Marie Colimore who was of three quarters Italian and one quarter French descent.[9] He was the oldest of four children (two brothers and a sister).[2] During Zappa's childhood, the family often moved because his father, a chemist and mathematician, had various jobs in the US defense industry. After a brief period in Florida in the mid-1940s, the family returned to Edgewood, Maryland where Zappa’s father got a job at the Edgewood Arsenal chemical warfare facility at nearby Aberdeen Proving Ground. Due to the home's proximity to the Arsenal which stored mustard gas, Zappa's father kept gas masks on hand in case of an accident.[10] This had a profound effect on the young Zappa: references to germs, germ warfare and other aspects of the defense industry occur throughout his work.[11]

As a child, Zappa was often sick, suffering from asthma, earaches and a sinus problem. A doctor treated the latter by inserting a pellet of radium on a probe into each of Zappa's nostrils.[10] Nasal imagery and references would appear both in his music and lyrics as well as in the collage album covers created by his long-time visual collaborator, Cal Schenkel. While little was known at the time about the potential dangers of living close to chemicals and being subjected to radiation, it is a fact that Zappa's illnesses peaked when he lived in the Baltimore area.[12][10]

In 1952, his family relocated mainly because of Zappa's asthma. They settled first in Monterey, California, where Zappa’s father taught metallurgy at the Naval Postgraduate School. Shortly thereafter, they moved to Claremont, then again to El Cajon before once again moving a short distance, to San Diego. During this period, his parents bought a record player, one event initiating Zappa’s interest in music, as he started collecting records.[13] Television also exerted a strong influence, as demonstrated by quotations from show themes and advertising jingles found in some of his later work.[14]

The first items of music Zappa purchased were R&B singles, and he began building a large collection he would keep for the rest of his life.[15] He was, however, mainly interested in sounds for their own sake, in particular, the sounds of drums and percussion. He got a snare drum at age twelve, and started learning the rudiments of orchestral percussion.[16] Events that initiated Zappa's deep engagement with modern classical music occurred when he was around thirteen.[17] He read a LOOK magazine story on the Sam Goody record store chain that lauded its ability to sell an LP as obscure as The Complete Works of Edgard Varèse, Volume One.[18] The story further described Varèse's percussion composition Ionisation produced by EMS Recordings as "a weird jumble of drums and other unpleasant sounds." Zappa then became convinced that he should seek out Varèse's music. When he finally found a copy after a year of searching (he noticed the LP for the "mad scientist" looking photo of Varèse on the cover), Zappa convinced the salesman to sell him the store's demonstration copy at a discount.[18] Thus began a lifelong passion for Varèse's music and that of other modern classical composers.

"Since I didn't have any kind of formal training, it didn't make any difference to me if I was listening to Lightnin' Slim, or a vocal group called the Jewels . . ., or Webern, or Varèse, or Stravinsky. To me it was all good music."

Frank Zappa, 1989[19]

Zappa therefore grew up influenced in equal measures by avant-garde composers such as Varèse, Igor Stravinsky and Anton Webern, R&B and doo-wop groups (particularly local pachuco groups), as well as modern jazz. His own heterogeneous ethnic background and the diverse cultural and social mix that existed in and around greater Los Angeles at the time were also crucial in situating Zappa as a practitioner and fan of "outsider art".[20] Indeed, throughout his career he was deeply distrustful and openly critical of "mainstream" social, political and musical movements, and he frequently lampooned popular musical fads like psychedelia, bubblegum pop, rock opera and disco.[21]

By 1955, the Zappa family moved to Lancaster, a small aerospace and farming town in Antelope Valley of the Mojave Desert, close to Edwards Air Force Base, Los Angeles, and the San Gabriel Mountains. Zappa's mother gave him considerable encouragement in his musical interests. Though she disliked Varèse's music, she was indulgent enough to award Zappa a long distance call to the composer as a fifteenth birthday present.[18] Unfortunately, Varèse was in Europe at the time, so Zappa spoke to the composer's wife. Zappa later received a letter from Varèse thanking Zappa for his interest, telling him about a composition he was working on called "Déserts." Living in the desert town of Lancaster, Zappa found this very exciting. Varèse invited Zappa to see him if he ever came to New York. The meeting never took place (Varèse died in 1965), but Zappa kept the framed letter displayed for the rest of his life.[17][22]

Zappa began his career as a musician on drums, and while attending Mission Bay High School in San Diego, he joined his first band, The Ramblers.[23] Although he performed as a singer and guitarist for most of his later career, Zappa's original influence by classical percussion compositions made him retain a strong interest in rhythm and percussion and his bands have been noted for the excellence of their drummers and percussionists. His works such as "The Black Page", written originally for drum kit but later developed for larger bands, are notorious for complexity in rhythmic structure, featuring radical changes of tempo and metre as well as short, densely arranged passages.[24][25]

In 1956 Zappa met Don Van Vliet (best known by his stage name "Captain Beefheart") while taking classes at Antelope Valley High School and playing drums in a local band, The Blackouts.[2] The Blackouts, a racially-mixed outfit, included Euclid James "Motorhead" Sherwood (who later became a member of the Mothers of Invention). Zappa and Van Vliet became close friends, influencing each other musically, and collaborating in the Sixties and mid-Seventies (e.g., on Van Vliet's Trout Mask Replica, which Zappa produced, and the 1975 Mothers of Invention live album Bongo Fury). They later became estranged for a period of years, but were in contact at the end of Zappa’s life.[26]

In 1957 Zappa was given his first guitar. Among his early influences were Johnny "Guitar" Watson, Howlin' Wolf and Clarence "Gatemouth" Brown (he would in the 1970s and 80s invite Watson to perform on several albums).[27] Zappa considered soloing as the equivalent of forming "air sculptures,"[28] and developed an eclectic, innovative and personal style. He eventually became one of the most highly regarded electric guitarists of his time.[29][30]

Zappa's interest in composing and arranging burgeoned in his later high school years where he started seriously dreaming of becoming a composer. By his final year at Antelope Valley High School, he was writing, arranging and conducting avant-garde performance pieces for the school orchestra.[31] Due to his family’s frequent moving, Zappa attended at least six different high schools, and as a student, Zappa was often bored and given to distracting the rest of the class with juvenile antics.[32] He graduated from Antelope Valley High School in 1958, and he would later acknowledge two of his music teachers on the sleeve of the 1966 album Freak Out![33] He left community college after one semester, and maintained thereafter a disdain for formal education, taking his children out of school at age 15 and refusing to pay for their college.[34]

Zappa left home in 1959, and moved into a small apartment in Echo Park, Los Angeles. After meeting Kathryn J. "Kay" Sherman during his short stay at college, they moved in together in Ontario, and got married in December 1960.[35] Around that time, Zappa worked for a short period in advertising. His sojourn in the commercial world was brief, but gave him valuable insights into how it works.[36] Throughout his career, Zappa always took a keen interest in the visual presentation of his work, designing some of his album covers and directing his own films and videos.

1960s

Zappa attempted to earn a living as a musician and composer, and played a variety of night-club gigs, some with a new version of The Blackouts.[37] Financially more important, however, were Zappa's earliest professional recordings, two soundtracks for the low-budget films The World's Greatest Sinner (1962) and Run Home Slow (1965). The former score was commissioned by actor-producer Timothy Carey, and was recorded in 1961. It contains many themes that would subsequently appear on later Zappa records.[38]The latter soundtrack was recorded in 1963, and was commissioned by one of Zappa’s former high school teachers as early as 1959. Zappa may therefore have worked on it years before its recording.[39] Excerpts from the soundtrack can be heard on the posthumous album The Lost Episodes (1996). During the early 1960s Zappa also wrote and produced songs for other local artists. Among those he worked with were singer-songwriter Ray Collins (their elegiac "Memories of El Monte" was recorded by Doo-Wop group The Penguins), and producer Paul Buff. Buff owned the small Pal Recording Studio in Cucamonga, which included a unique 5-track tape recorder built by himself. At this time, only a handful of the most expensive commercial studios had multi-track facilities, and the industry standard for smaller studios was still mono or two-track.[40] Although none of the recordings from the period achieved major commercial success, Zappa earned money allowing him to stage a concert of his orchestral music in 1963 as well as broadcasting and recording it.[41] Also, he appeared on the Steve Allen Show the same year where he played a bicycle.[42]

With his income from composing, Zappa bought the financially strained Pal Studio from Paul Buff, and renamed it "Studio Z." After his marriage started to break up, he moved into the studio in late 1963 and began routinely working 12 hours or more per day recording and experimenting with overdubbing. This set a pattern that would endure for almost all of his life.[43] As Studio Z was rarely booked for recordings by other musicians, Zappa accepted in March 1965 an offer of $100 to produce a suggestive audio tape for a customer's stag party. Zappa and a female friend jokingly faked an "erotic" recording. The customer, however, was an undercover member of the Vice Squad and Zappa was jailed for ten days on charges of supplying pornography.[2] His entrapment and brief imprisonment left a permanent mark, and was a key event in the formation of his anti-authoritarian stance.[44] In addition, Zappa lost several recordings made at Studio Z in the process, and eventually he could no longer afford having the studio.[45]

In 1965 Zappa was approached by Ray Collins who asked Zappa to join a local R&B band, The Soul Giants, as a guitarist.[2] Zappa accepted, and soon he assumed leadership and convinced the other band members that they should play his music so as to increase the chances of getting a record contract.[46] The band was renamed "The Mothers" on Mothers Day. The group increased their bookings after beginning an association with manager Herb Cohen, and they gradually began to gain attention on the burgeoning Los Angeles underground scene.[47] In early 1966, they were spotted by leading record producer Tom Wilson, when playing “Trouble Every Day”, a song about the Watts Riots.[48] Wilson had earned acclaim as the producer for Bob Dylan and Simon & Garfunkel, and was also notable as one of the few African-Americans working as a major label pop producer at this time. Wilson signed The Mothers to the Verve division of MGM, which had built up a strong reputation for its modern jazz recordings in the 1940s and 1950s, but was then attempting to diversify into pop and rock, with an "artistic" or "experimental" bent. Verve Records insisted that the band officially re-titled themselves "The Mothers of Invention" because "Mother" was short for "motherfucker" – a term that apart from its profane meanings can denote a skilled musician.[49]

With Wilson credited as producer, The Mothers of Invention and a studio orchestra recorded the groundbreaking double-album Freak Out! (1966). It mixed R&B, doo-wop and experimental sound collages that captured the "freak" subculture of Los Angeles at that time,[50] The album immediately established Zappa as a radical new voice in rock music, providing an antidote to the “relentless consumer culture of America.[51] The sound was raw, but the arrangements were sophisticated. The lyrics praised non-conformity, disparaged authorities and had dadaist elements. Yet, there was place for seemingly conventional love songs.[52] Most compositions are Zappa’s and this would set a precedent for the rest of the recordings of his career. He also had full control over the arrangements and musical decisions (and did most overdubs himself).[53] Wilson, however, provided the industry clout and connections to get the unknown group financial resources needed.[54]

During the recording of Freak Out!, Zappa moved into a house in Laurel Canyon with friend Pamela Zarubica, who appeared on the album.[55] The house became a meeting (and living) place for many LA musicians and groupies of the time, despite Zappa’s disapproval of people on drugs.[56] He would label them “assholes in action,” and he only tried marijuana a few times without any pleasure[57] After a short promotional tour following the release of Freak Out!, Zappa met Adelaide Gail Sloatman (b. January 1, 1945). Zappa fell in love within “a couple of minutes,” and she moved into the house over the summer.[58] They married in 1967.

Wilson also produced the follow-up album Absolutely Free (1967), which was recorded in November 1966, and later mixed in New York. It featured an extended version of the Mothers of Invention and focused more on songs that defined Zappa’s compositional style of introducing abrupt rhythmical changes into songs that from the first place were build of different elements.[59] Examples are “Plastic People” and “Brown Shoes Don’t Make It”, which contained lyrics critical of the hypocrisy and conformity of American society but also of the people fighting it in the Sixties. As Zappa put it: “we’re satirists, and we are out to satirise everything.”[60] At the same time, Zappa had recorded material for a self-produced album based on orchestral works to be released under his own name. Due to contractual problems, however, the recordings were shelved and only made ready for release late in 1967. Zappa then took the opportunity to radically restructure the contents and adding newly recorded improvised dialogue, in order to finalize his first solo album (under the name Francis Vincent Zappa[1]), Lumpy Gravy (1968).[61] It is an “incredible ambitious musical project,”[62] a "monument to John Cage,"[63] which intertwines orchestral themes (many that would appear again in other forms on later albums), spoken words and electronic noises through radical audio editing techniques.[64]

The Mothers of Invention played in New York in late 1966, and being successful, they were offered a contract at the Garrick Theatre during Easter 1967. This also proved successful, and Herb Cohen managed to extend the booking, which eventually came to last half a year.[65] As a result, Zappa and his wife, along with the Mothers of Invention, moved to New York.[66] Their shows became a combination of improvised acts showcasing the individual talents of the band as well as tight performances of Zappa’s music. Everything directed by Zappa’s famous hand signals.[67] Guest performers appeared, and audience participation became a regular part of the Garrick shows. At one evening, Zappa managed to entice some U.S. Marines from the audience onto the stage, where they proceeded to dismember a big baby doll, having been told by Zappa to pretend that it was a "gook baby".[68]

Situated in New York, and only interrupted by the band’s first European tour, the Mothers of Invention recorded the album widely regarded as the peak of the group's late Sixties work, We're Only in It for the Money (released 1968).[69] It was produced by Zappa, with Wilson credited as executive producer. From then on, Zappa would produce all albums released by the Mothers of Invention or as a solo artist. We're Only in It for the Money featured some of the most creative audio editing and production yet heard in pop music, and the songs ruthlessly satirized the hippie and flower power phenomena.[70] The cover photo parodied that of The Beatles' Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[71] In conformity with Zappa’s eclectic approach to music, the following album was very different as it represented a collection of doo-wop songs, Cruising with Ruben & the Jets (1968). Listeners and critics were not sure whether the album was a satire or a tribute.[72] Zappa has noted himself that the album was conceived like Stravinsky’s compositions in his neo-classical period: “If he could take the forms and clichés of the classical era and pervert them, why not do the same . . . to doo-wop in the fifties?”[73] Indeed, the theme from Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring is heard during one song.

While in New York, Zappa increasingly used tape editing as a compositional tool.[74] A prime example is found on the double album Uncle Meat (1969),[75] where the track "King Kong" is edited from various studio and live performances. Zappa had begun regularly recording concerts,[76] and because of his insistence on precise tuning and timing in concert, Zappa was able to augment his studio productions with excerpts from live shows, and vice versa.[77] Later, he would combine recordings of different compositions into new pieces, irrespective of the tempo or meter of the sources. He dubbed this process xenochrony (alien time).[78][77] Zappa moreover evolved a compositional approach, which he called "conceptual continuity." The idea was that any project or album was part of a larger project. Everything was connected, and musical themes and lyrics would reappear in different form on later albums. Conceptual continuity clues are found throughout Zappa's entire oeuvre.[74][14]

During the late Sixties, Zappa also continued to develop the business sides of his career. He and Herb Cohen formed the Bizarre Records and Straight Records labels distributed by Warner Bros. Records, as ventures to aid the funding of projects and increase creative control. Zappa produced the double album Trout Mask Replica for Captain Beefheart, and releases by Alice Cooper, Tim Buckley, Wild Man Fischer, The GTOs as well as Lenny Bruce's last live performance.[79]

Zappa and the Mothers of Invention returned to Los Angeles in the summer of 1968, and the Zappas moved into a house on Laurel Canyon Boulevard, only to move to a house on Woodrow Wilson Drive in the autumn.[80] This would become the place Zappa lived until his death. Although the Mothers of Invention had fantastic success in Europe and England, had fanatic fans everywhere, they were not doing that well.[81] In 1969 there were nine members, and Zappa was supporting the group himself from his publishing royalties whether they played or not. In late 1969, Zappa therefore broke up band due to financial strain. Although this caused some bitterness among band members,[82] several would return to Zappa in years to come. Remaining recordings with the band from this period were collected on Weasels Ripped My Flesh and Burnt Weeny Sandwich (both 1970).

After he disbanded the Mothers of Invention, Zappa released the acclaimed solo album Hot Rats (1969).[83][84] It features, for the first time on record, Zappa playing extended guitar solos. Also, it contains one of Zappa’s most enduring compositions, “Peaches En Regalia,” which would reappear several times on future recordings.[85] Everything backed by jazz, blues and R&B session players including violinist Don "Sugarcane" Harris, drummer John Guerin, multi-instrumentalist and previous member of Mothers of Invention Ian Underwood, and bassist Shuggie Otis, along with a guest appearance by Captain Beefheart (providing vocals to the only non-instrumental track, “Willie the Pimp”). It became a very popular album in England,[86] and had a major influence on the development of the jazz-rock fusion genre.[85][84]

1970s

Zappa kept composing music for symphony orchestra while playing and recording with the Mothers of Invention. He made contact with conductor Zubin Mehta and a concert was arranged in May 1970 where Metha conducted the Los Angeles Philharmonic amended with a rock band. The music, “200 Motels,” was according to Zappa the result of three years work, and was mainly written in motels while on tour.[87] While the concert was a success, Zappa’s experience of working with a symphony orchestra was not a happy one.[88] This would be a recurring issue in his career, where he often felt that the money he had to spend on getting his classical music performed rarely matched the resulting output.[89]

In late 1970, Zappa put together a new version of The Mothers (from then on, he mostly dropped the "of Invention"). It included British drummer Aynsley Dunbar, jazz keyboardist George Duke, Ian Underwood, Jeff Simmons (bass, rhythm guitar), and three members of The Turtles: bass player Jim Pons, and singers Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan, who due to persisting legal/contractual problems adopted the stage-monikers "The Phlorescent Leech and Eddie," or "Flo & Eddie" for short.[90]

This new lineup debuted on Zappa's next solo album Chunga's Revenge (1970).[91], which was followed by the double-album soundtrack to the movie 200 Motels (1971), featuring The Mothers, The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and, among others, Ringo Starr, Theodore Bikel and Keith Moon. The film, co-directed by Zappa and Tony Palmer, was shot in a week on a large sound stage outside of London.[92] The film dealt loosely with life on the road as a rock musician.[93] It was shot on video, and transferred to 35 mm film, and was released to mixed reviews.[92] The music relied extensively on orchestral music, and Zappa’s ongoing dissatisfaction with the classical music world gained strength, as a concert at the Royal Albert Hall prior to the beginning of filming was canceled. The reason for the cancellation was that a representative of the Royal Albert Hall found some of the lyrics obscene. Zappa lost money due to the cancellation as well as important rehearsals of his complex compositions. He would in 1975 lose a lawsuit against the Royal Albert Hall for breach of contract.[94]

After 200 Motels, the band went on tour, which resulted in two live albums, Fillmore East - June 1971 and Just Another Band From L.A., which included the 20-minute track "Billy The Mountain," Zappa's satire on rock opera, set in Southern California. This track was representative for the band’s theatrical performances (the band was dubbed the “Vaudeville Band”), where songs were used to build up sketches based on “200 Motels” scenes as well as new situations often portraying the band members’ sexual encounters on the road.[95][96]

In December 1971 there were two serious setbacks. While performing at Casino de Montreux in Switzerland, the Mothers' equipment was destroyed when a flare set off by an audience member started a fire that burned down the casino.[97][98] After a week’s break, The Mothers went to play at the Rainbow Theatre, London with rented gear. During an encore, an audience member pushed Zappa off the stage and into the concrete-floored orchestra pit.[99] The band thought Zappa had been killed, but he had suffered serious fractures, head trauma and injuries to his back, leg, and neck, as well as a crushed larynx (which caused his voice to drop a third after healing).[97] This left him wheelchair bound for a time, forcing him off the road for over half a year. Upon his return to the stage in September 1972, he was still wearing a leg brace for a period thereafter, had a noticeable limp and could not stand for very long while on stage. Zappa noted that one leg healed "shorter than the other" (a reference later found in the lyrics of songs "Zomby Woof" and "Dancin' Fool"), which was cause of chronic back pains for years.[97] Meanwhile, the Mothers were left in limbo, and eventually formed the core of Flo and Eddie's band as they set out on their own.

In 1971-72 Zappa released two strongly jazz-oriented solo LPs, Waka/Jawaka and The Grand Wazoo, which were recorded during the forced layoff from concert touring, using floating line-ups of session players and Mothers alumni.[100] Musically, the albums were close to that of Hot Rats.[101] Zappa began touring again in late 1972.[101] First with a series of concerts with a 20-piece big-band and later with a scaled-down unit named "Petit Wazoo."[102] He then formed and toured with smaller groups that variously included Ian Underwood (reeds, keyboards), Ruth Underwood (vibes, marimba), Sal Marquez (trumpet, vocals), Napoleon Murphy Brock (sax, flute and vocals), Bruce Fowler (trombone), Tom Fowler (bass), Chester Thompson (drums), Ralph Humphrey (drums), George Duke (keyboards, vocals) and Jean-Luc Ponty (violin).

By 1973 the Bizarre and Straight labels were discontinued. In their place Zappa and Cohen created DiscReet Records, also distributed by Warner Bros.[103] Zappa continued a high rate of production through the first half of the 1970s, including the solo album Apostrophe (') (1974), which reached a career-highest #10 on the Billboard pop album charts[104] helped by the chart single “Don’t Eat The Yellow Snow.”[105] Among other albums from the period is Over-Nite Sensation (1973), which contained several future concert favorites. It is by some considered one of Zappa’s best albums.[106] The albums Roxy & Elsewhere (1974) and One Size Fits All (1975) feature ever-changing versions of a bands still called the Mothers, and were notable for the tight renditions of the highly difficult jazz-fusion songs, demonstrated by such pieces as "Inca Roads," "Echidna's Arf (Of You)" or "Be-Bop Tango (Of the Old Jazzmen's Church)." [107] A live recording from 1974, You Can't Do That on Stage Anymore, Vol. 2 (1988), captures "the full spirit and excellence of the 1973-75 band."[107] Zappa would also release Bongo Fury (1975), which featured live recordings from a tour the same year that reunited him with Captain Beefheart for a brief period.[108].

Zappa's relationship with long-time manager Herb Cohen ended in 1976. The break up was an acrimonious affair, where Zappa sued Cohen for skimming more than he was allocated from DiscReet Records, as well as signing on acts that Zappa did not approve of.[109] Cohen filed a lawsuit against Zappa in return, which froze the money Zappa and Cohen had gained from an out-of-court settlement with the MGM over the rights of the early Mothers of Invention recordings, as well as preventing Zappa access to any of his previously recorded material during the trials. Zappa therefore took his personal master copies of the rock-oriented Zoot Allures (1976) directly to Warner Bros., thereby bypassing DiscReet.[110]

In the mid 1970s Zappa had prepared material for Läther (pronounced "leather"), a four-LP project. Läther encapsulated all the aspects of Zappa's musical styles —rock tunes, orchestral works, complex instrumentals, and Zappa's own trademark tube distortion-drenched guitar solos. Wary of a quadruple-LP, Warner Bros. Records refused to release it.[111] Zappa managed to get an agreement with Mercury-Phonogram, and test pressings were made targeted at a Halloween 1977 release. Warner Bros. prevented the release, however, as they claimed right over the material.[112] Zappa responded by appearing on the Pasadena, California radio station KROQ, allowing them to broadcast Läther and encouraging listeners to make their own tape recordings.[113] A lawsuit between Zappa and Warner Bros. followed, during which no Zappa material was released for more than a year. Eventually, Warner Bros. issued major parts of Läther against Zappa’s will, as four individual albums with limited promotion.[114] Läther was released posthumously in 1996.[115]

Although Zappa eventually gained the rights of all his material created under the MGM and Warner Bros. contracts,[116] the various lawsuits meant that for a period Zappa’s only income would come from touring, which he therefore did extensively in 1975-77 with relatively small, mainly rock-oriented, bands.[117] Drummer Terry Bozzio became a regular band member, Napoleon Murphy Brock stayed on for a while, and original Mothers of Invention bassist Roy Estrada joined. Among other musicians were bassist Patrick O’Hearn, singer-guitarist Ray White and keyboardist Eddie Jobson. In December 1976, Zappa appeared as a featured musical guest on the NBC television show Saturday Night Live.[118][119] His performances included an impromptu musical collaboration with cast member John Belushi during the instrumental piece "The Purple Lagoon." Belushi appeared as his Samurai Futaba character playing the tenor sax with Zappa conducting.[120] Also, "I'm The Slime", featuring a voice-over by SNL booth announcer Don Pardo, was performed. Zappa’s current touring band extended with Ruth Underwood and a horn section (featuring Michael and Randy Brecker), performed then a number of Christmas shows in New York, of which recordings which appear on one of the albums released by Warner Bros., Zappa in New York (1978). It mixes intense instrumentals such as “The Black Page, # 1 & 2” as well as humorous songs as “Titties and Beer” and “The Illinois Enema Bandit” (with Don Pardo providing the opening narrative).[121] The latter song about sex criminal Michael H. Kenyon contained, as did many lyrics on the album, numerous sexual references. While Zappa had always been explicit about sexuality, his continued insistence on being so fared negatively with some critics.[122] Zappa himself dismissed the criticism by noting that he was like a journalist reporting on life as he saw it in his songs.[123] Also, predating his later fight against censorship in music, he noted that “What do you make of a society that is so primitive that it clings to the belief that certain words in its language are so powerful that they could corrupt you the moment you hear them.”[124]

The remaining albums released by Warner Bros. without Zappa’s consent were Studio Tan (1978) and Sleep Dirt (1979), containing many complex suites of instrumentally based tunes (recorded between 1973 and 76), which became overlooked in the midst of all the legal hassles,[125] and Orchestral Favorites (1979), featuring recordings of a concert with orchestral music Zappa had put together at UCLA back in September 1975.

Getting successfully out of the lawsuits, Zappa ended the 1970s period “stronger than ever,”[126] by releasing two of his most successful albums in 1979. His best selling album ever, Sheik Yerbouti,[127] and the “bona fide masterpiece,”[126] Joe's Garage.[128] The double album Sheik Yerbouti (1979) was the first release on Zappa Records, and contained songs such as Grammy-nominated single "Dancin' Fool" (that reached #45 on the Billboard charts[129] ), and "Jewish Princess," which received controversial attention as a Jewish lobby group, “Anti-Defamation League,” tried to prevent the song from getting airplay due to its alleged anti-Semitic lyrics.[130] Zappa vehemently denied any anti-Semitic sentiments and discarded the ADL as a “noisemaking organization that tries to apply pressure on people in order to manufacture a stereotype image of Jews that suits their idea of a good time.”[131] The album’s commercial success was attributable partly due to the song "Bobby Brown." Due to its explicit lyrics about a young man's encounter with a "dyke by the name of Freddie," the song did not get airplay in the US, but it topped the charts in several European countries and is still popular in countries where English is not the primary language.[132] The triple LP Joe's Garage features lead singer Ike Willis as voice of "Joe" in a rock opera about danger of systems,[133] the suppression of freedom of speech and music — inspired in part by the Islamic revolution that had made music illegal at time[134] — and about the “strange relationship Americans have with sex and sexual frankness.”[133] The album contains rock songs like "Catholic Girls" (a riposte to the controversies of "Jewish Princess"[135]), "Lucille Has Messed My Mind Up," and the title track, as well as extended live-recorded guitar improvisations combined with a studio backing band dominated by drummer Vinnie Colaiuta (with whom Zappa had a particularly good musical rapport[136]) adopting the aforementioned xenochrony process. Finally, the album contains what would become one of Zappa's most famous guitar "signature pieces," "Watermelon in Easter Hay."[137][28]

On December 21, 1979, Zappa’s movie Baby Snakes premièred in New York. The movie was “About people who do stuff that is not normal.”[138] The 2 hour and 40 minutes movie was based on footage from a number of concerts in front of a New York audience around Halloween 1977. It also contained several extraordinary sequences of clay animation by Bruce Bickford who had earlier provided animation sequences for Zappa to a 1974 TV special (which would later become available on the video The Dub Room Special (1982)).[139] The movie did not do well in theatrical distribution,[140] but won in 1981 the Premier Grand Prix at the First International Music Festival in Paris. It became available on DVD in 2003.[139]

1980s

After spending most of 1980 on the road, Zappa released Tinsel Town Rebellion in 1981. It was the first release on Barking Pumpkin Records,[141] and it contains songs taken from a 1979 tour, one studio track and material from the 1980 tours. The album is a mixture of complicated instrumentals and Zappa's use of sprechstimme (speaking song or voice) — a compositional technique utilized by such composers as Arnold Schoenberg and Alban Berg — showcasing some of the most accomplished bands Zappa ever had (mostly featuring drummer Vinnie Colaiuta).[141] While some lyrics would still raise controversy among critics, in the sense that some found them sexist,[142] the political and sociological satire in songs like the title track and “The Blue Light” have been described as “hilarious critique of the willingness of the American people to believe anything.”[143] The album is also notable for the presence of guitar virtuoso Steve Vai, who joined Zappa's touring band in the Fall of 1980.[144]

The same year the double album You Are What You Is was released. Most of the album was recorded in Zappa's brand new Utility Muffin Research Kitchen (UMRK) studios, which were located at his house,Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). The album included one complex instrumental, "Theme from the 3rd Movement of Sinister Footwear," but focused mainly on rock songs with Zappa's sardonic social commentary -- satirical lyrics targeted at teenagers, the media, and religious and political hypocrisy.[145] "Dumb All Over" is a tirade on religion, as is "Heavenly Bank Account," wherein Zappa rails against TV evangelists such as Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson for their purported influence on the US administration as well as their use of religion as a means of raising money.[146] Songs like “Society Pages” and “I’m a Beautiful Guy” showed Zappa’s dismay with the Reaganite era and its “obscene pursuit of wealth and happiness.”[146]

1981 also saw the release of three instrumental albums Shut Up 'N Play Yer Guitar, Shut Up 'N Play Yer Guitar Some More, and The Return of the Son of Shut Up 'N Play Yer Guitar, which were initially sold via mail order by Zappa himself, but were later released commercially through CBS label due to popular demand.[147] The albums focus exclusively on Frank Zappa as a guitar soloist, and the tracks are predominantly live recordings from 1979-80, and highlight Zappa's improvisational skills with “beautiful recordings from the backing group as well.”[148] The albums were subsequently released as a 3-album box set, and were in 1988 followed by the album Guitar focusing on recordings from 1981-82 and 1984. A third guitar-only album, Trance-Fusion, completed by Zappa shortly before his death, featuring solos recorded between 1979 and 1988 (with an emphasis on 1988) was released in 2006.

In May 1982, Zappa released Ship Arriving Too Late to Save a Drowning Witch, which featured his biggest selling single ever, the Grammy nominated "Valley Girl" (topping out at #32 on the Billboard charts[129]). In her improvised "lyrics" to the song, Zappa's daughter Moon Unit satirized the vapid speech of teenage girls from the San Fernando Valley, which popularized many "Valspeak" expressions such as "gag me with a spoon" and "barf out."[149] Most Americans who only knew Zappa from his few singles successes, would now think of him as a person writing “novelty songs,” even though the rest of the album contained highly challenging music.[150] Zappa was somewhat irritated by this,[151] and never played the song live.[150]

1983 saw the release of two different projects, beginning with The Man From Utopia, a rock-oriented work. The album itself is eclectic, featuring the vocal-led "Dangerous Kitchen" and "The Jazz Discharge Party Hats," both continuations of the “Sprechstimme” excursions on Tinseltown Rebellion. The second album, London Symphony Orchestra, Vol. 1 contained orchestral Zappa compositions conducted by Kent Nagano and performed by the London Symphony Orchestra. A second record of these sessions, London Symphony Orchestra, Vol. 2 was released in 1987. The material was recorded under a tight schedule, and with Zappa himself providing all funding.[152] It came after Zappa had experienced a few unsuccessful and financially costly attempts to have his orchestral works performed.[152] Zappa was not pleased with the LSO recordings as they were not perfect performances of his compositions. The most notable example is "Strictly Genteel," which was recorded after the trumpet section had been out for drinks on a break.[153] The track took 40 edits to hide out-of-tune notesCite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). Some reviews noted that the recordings were the best representation of Zappa’s orchestral work so far.[154]

For the remainder of his career, much of Zappa's work was affected by use of the synclavier as a compositional and performance tool. With the complex music he wrote, the synclavier represented anything you could dream up.[155] One could program the synclavier to play almost anything conceivable to perfection. “With the Synclavier, any group of imaginary instruments can be invited to play the most difficult passages . . . with one-millisecond accurary – every time.”[155] Even though it essentially did away with the need for musicians,[156] Zappa viewed the synclavier and real-life musicians as separate things.[155] In 1984, he released four albums. Boulez Conducts Zappa: The Perfect Stranger, which juxtaposed orchestral works commissioned and conducted by world-renowned conductor Pierre Boulez (which was listed as an influence on Freak Out!) and performed by his Ensemble InterContemporain, as well as premiere synclavier pieces. Again, Zappa was not satisfied with the performances of his orchestral works as he found it under rehearsed, but in the album liner notes he does respectfully thank Boulez for his demands for precision.[157] The synclavier pieces stood in contrast to the orchestral works, as all sounds were electronically generated and not, as became possible shortly thereafter, sampled.

The album Thing-Fish was an ambitious three-record set in the style of a Broadway play dealing with a dystopian "what-if" scenario involving feminism, homosexuality, manufacturing and distribution of the AIDS virus, and a eugenics program conducted by the United States government.[158] New vocals were combined with previously released tracks and new synclavier music, and therefore "the work is an extraordinary example of bricolage" in Zappa's production.[159] Finally, 1984 saw Francesco Zappa a synclavier rendition of works by 17th century composer, Francesco Zappa (no relation), and Them or Us, a two-record set of heavily edited live and session pieces.

On September 19, 1985, Zappa testified before the US Senate Commerce, Technology, and Transportation committee, attacking the Parents Music Resource Center or PMRC, a music censorship organization, founded by then-Senator Al Gore's wife Tipper Gore. The PMRC consisted of many wives of politicians, including the wives of five members of the committee. In his prepared statement, Zappa said

"The PMRC proposal is an ill-conceived piece of nonsense which fails to deliver any real benefits to children, infringes the civil liberties of people who are not children, and promises to keep the courts busy for years dealing with the interpretational and enforcemental problems inherent in the proposal's design. It is my understanding that, in law, First Amendment issues are decided with a preference for the least restrictive alternative. In this context, the PMRC's demands are the equivalent of treating dandruff by decapitation. (...) The establishment of a rating system, voluntary or otherwise, opens the door to an endless parade of moral quality control programs based on things certain Christians do not like. What if the next bunch of Washington wives demands a large yellow "J" on all material written or performed by Jews, in order to save helpless children from exposure to concealed Zionist doctrine?"[160]

Zappa put some excerpts from the PMRC hearings to synclavier-music in his composition "Porn Wars" from the 1985 album Frank Zappa Meets the Mothers of Prevention. Zappa is heard interacting with Senators Fritz Hollings, Slade Gorton, Al Gore (who admitted to being a Zappa fan), and, most notably, an exchange with Florida Senator Paula Hawkins over what toys the Zappa children played with. Zappa would also go on to argue with PMRC representatives on the CNN's Crossfire in 1986 and 1987.[161]

The album Jazz From Hell, released in 1986, earned Zappa his first Grammy Award in 1988 for Best Rock Instrumental Performance. Except for one live guitar solo, the album exclusively featured compositions brought to life by the synclavier. Although an instrumental album, Meyer Music Markets sold Jazz from Hell featuring an "explicit lyrics" sticker (a warning label introduced by the Recording Industry Association of America in an agreement with the PMRC).[162]

His last tour in a rock band format took place in 1988 with a 12-piece group which had a repertoire of over 100 (mostly Zappa) compositions, but which split in acrimonious circumstances before the tour was completed.[163] The tour was documented on the albums Broadway The Hard Way (new material featuring songs with strong political emphasis), The Best Band You Never Heard in Your Life (Zappa "standards" and an eclectic collection of cover tunes, ranging from Maurice Ravel's "Boléro" to Led Zeppelin's "Stairway to Heaven"), and Make a Jazz Noise Here (mostly instrumental and experimental music). Parts are also found on You Can't Do That on Stage Anymore, volumes 4 and 6.

In the late 1980s Zappa's passion for American politics was becoming a bigger part of his life. Throughout the 1988 tour, he regularly encouraged his young fans to register to vote, and even had voter registration booths at his concerts.[164] He was also considered as a nominee for President of the United States on the Libertarian ticket.[165]

Around 1986, Zappa undertook a comprehensive re-release program of his earlier recordings.[166] He personally oversaw the remastering of all his 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s albums for the new compact disc medium. Certain aspects of these re-issues were, however, criticised by some fans as being unfaithful to the original recordings.[167]

1990s

In early 1990, Zappa visited Czechoslovakia at the request of President Václav Havel, a lifelong fan, and was asked by Havel to serve as consultant for the government on trade, cultural matters and tourism. Zappa enthusiastically agreed and began meeting with corporate officials interested in investing in Czechoslovakia. Within a few weeks, however, the US administration put pressure on the Czech government to withdraw the appointment. Havel made Zappa an unofficial cultural attaché instead.[168]

Zappa's political work would soon come to a halt, however. In 1991, he was diagnosed with terminal prostate cancer.[169] After his diagnosis, Zappa devoted most of his energy to modern orchestral and synclavier works.

In 1992, he was approached by the German chamber ensemble Ensemble Modern who was interested in playing his music. Although ill, Zappa invited them to Los Angeles for rehearsals of new compositions as well as new arrangements of older material.[170] In addition to being satisfied with the ensemble’s performances of his music, Zappa also got along with the musicians, and concerts in Germany and Austria were set up for the fall.[170] In September 1992, the concerts went ahead as scheduled, but Zappa could only appear at two in Frankfurt due to illness. At the first concert, he conducted the improvised opening, and the final “G-Spot Tornado” as well as the theatrical “Food Gathering in Post-Industrial America, 1992” and “Welcome to the United States” (the remainder of the program was conducted by the ensemble’s regular conductor Peter Rundel). Zappa received a 20-minute ovation.[171] It would become his last public appearance in a musical function, as the cancer was spreading to an extent where he was in too much pain to enjoy himself by what he would otherwise call an “exhilarating” event.[172] Recordings from the concerts appeared on The Yellow Shark (1993), Zappa’s last release when alive, and some material from studio rehearsals appeared on the posthumous Everything Is Healing Nicely (1999).

In 1993, prior to his death, he completed Civilization, Phaze III, a major synclavier work he had begun in the 1980s. Frank Zappa died on December 4, 1993, age 52, from prostate cancer. He was interred in an unmarked grave at the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Westwood, California.[169]

Discography

Notes and references

- ^ a b Until discovering his birth certificate as an adult, Zappa believed he had been christened "Francis," and he is credited as Francis on some of his early albums. His real name was "Frank", however, never "Francis." Cf. Zappa, Frank (1989). The Real Frank Zappa Book. New York: Poseidon Press. ISBN 0-671-63870-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e "Frank Zappa". The New Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster Inc. 1993. ISBN 0-684-81044-1.

- ^ "The Immortals". Rolling Stone Issue 972. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ Pitts, Johnathan (2007-08-05). "Zappa redux". The Baltimore Sun. baltimoresun.com. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ^

Ouellette, Dan (August 1993). "Interview with Frank Zappa". Pulse! Magazine. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Miles, Barry (2004). Frank Zappa. London: Atlantic Books. pp. p. 345, p. 56. ISBN 1 84354 092 4.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Lowe, Kelly Fisher (2006). The Words and Music of Frank Zappa. Westport: Praeger Publishers. pp. p. 197-203. ISBN 0-275-98779-5.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, pp. 113-122.

- ^ Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, pp. 20-23.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, pp. 8-9.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 10.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 12.

- ^ a b For a comprehensive list of the appearance of parts of "old" compositions or quotes from others' music in Zappa's catalogue, see "FZ Musical Quotes". Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 36

- ^ Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 29.

- ^ a b

Zappa, Frank (June 1971). "Edgard Varese: The Idol of My Youth". Stereo Review. pp. 61–62. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 30-33.

- ^ Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 34.

- ^ Watson, Ben (1996). Frank Zappa: The Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312141246.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Among his many musical satires are the 1967 songs "Flower Punk" (which parodies the song "Hey Joe") and "Who Needs The Peace Corps?", which are withering critiques of the late-Sixties commercialisation of the hippie phenomenon.

- ^ On several of his earlier albums, Zappa paid tribute to Varèse by quoting his: "The present-day composer refuses to die."

- ^ Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 29.

- ^ Clement, Brett (2004). "Little dots: A study of the melodies of the guitarist / composer Frank Zappa (pdf file)" (PDF). Master Thesis. The Florida State University, School of Musik. pp. pp. 25-48. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Hemmings, Richard (2006). "Ever wonder why your daughter looked so sad? Non-danceable beats: getting to grips with rhythmical unpredictability in Project/Object". Working Paper. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 372.

- ^ Mike Douglas (1976). The Mike Douglas Show (TV show). YouTube. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ^ a b The other signature pieces are "Zoot Allures" and "Black Napkins" from Zoot Allures. See Zappa, Dweezil (1996). "Greetings music lovers, Dweezil here". Liner Notes, Frank Zappa Plays the Music of Frank Zappa: A Memorial Tribute.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link). - ^ He is ranked 45th in "The 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time". Rolling Stone. August 27, 2003.

- ^ He is ranked 51st in "The 100 Wildest Guitar Heroes". Classic Rock. April 2007.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 40.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 48.

- ^

Walley, David (1980). No Commercial Potential. The Saga of Frank Zappa. Then and Now. New York: E. P. Dutton. pp. p. 23. ISBN 0-525-93153-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 345.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 58.

- ^ Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 40.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 59.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 63.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 55.

- ^ Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 42.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 74.

- ^ Steve Allen (1963). The Steve Allen Show (TV show). myspacetv.com. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 43.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. XV.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 87.

- ^ Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 65-66.

- ^ Walley, 1980, No Commercial Potential, p. 58.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 103.

- ^ Nigel Leigh (March 1993). Interview with Frank Zappa (BBC Late Show). UMRK, Los Angeles, CA: BBC.

- ^ Walley, 1980, No Commercial Potential, p. 60-61.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 115.

- ^ Watson, Ben (2005). Frank Zappa. The Complete Guide to His Music. London: Omnibus Press. pp. pp. 10-11. ISBN 1-84449-865-4.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Some of the hired session musicians were shocked that they should read from charts and have Zappa conducting them. This was not what they expected at a rock session. See Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 112.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 123.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 112.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 122.

- ^ Loden, Kurt (1988). "Rolling Stone Interview". Rolling Stones Magazine. Retrieved 2008-01-04.

- ^ Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 65-66.

- ^ Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 5.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 135-138.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 140-141.

- ^ Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 56.

- ^ Walley, 1980, No Commercial Potential, p. 86.

- ^ Couture, François. "Lumpy Gravy. Review". Allmusic.com. Retrieved 2008-01-02. Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 56.

- ^

James, Billy (2000). Necessity Is . . .: The Early Years of Frank Zappa & the Mothers of Invention. London: SAF Publishing Ltd. pp. pp. 62-69. ISBN 0-946-71951-9.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 140-141.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 147.

- ^ Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 94.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "We're Only in It for the Money. Review". Allmusic.com. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

- ^ Watson, 2005, Frank Zappa. The Complete Guide to His Music, p. 15. Walley, 1980, No Commercial Potential, p. 90.

- ^ As the legal aspects of using the Sgt Pepper concept were unsettled, however, the album was released with the cover and back on the inside of the gatefold, while the actual cover and back were a picture of the group in a pose parodying the inside of the Beatles album. Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 151.

- ^ Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 58.

- ^ Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 88.

- ^ a b Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 160.

- ^ James, 2000, Necessity Is . . ., p. 104.

- ^ In the process, he built up a vast archive of live recordings. In the late 1980s some of these recordings were collected for the 12-CD set You Can't Do That on Stage Anymore.

- ^ a b Chris Michie (January 2003). "We are the Mothers...and This Is What We Sound Like!". MixOnline.com. Retrieved 2008-01-04.

- ^ Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 56.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 173-175.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 178.

- ^ Walley, 1980, No Commercial Potential, p. 116.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 186.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "Hot Rats. Review". Allmusic.com. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

- ^ a b Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 194.

- ^ a b Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 74.

- ^ Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 109.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 198.

- ^ Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 88.

- ^ Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, pp. 142-156.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 201.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 205.

- ^ a b Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 94.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 207.

- ^ Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, pp. 119-137.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, pp. 203-204.

- ^ During the June 1971 Fillmore concerts Zappa was joined on stage by John Lennon and Yoko Ono. This performance was recorded, and Lennon released excerpts on his album Some Time In New York City in 1972. Zappa later released his version of excerpts from the concert on Playground Psychotics in 1992, including the jam track "Scumbag" and an extended avant-garde vocal piece by Yoko (originally called "Au"), which Zappa renamed "A Small Eternity with Yoko Ono".

- ^ a b c Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, pp. 112-115.

- ^ The event, immortalized in Deep Purple's song "Smoke on the Water," and immediate aftermath can be heard on the bootleg album Swiss Cheese/Fire, released legally as part of Zappa's Beat the Boots II compilation.

- ^ The attacker, Trevor Howell, gave two stories to the press: one was that he felt the band hadn't given him value for his money; the other was that Zappa had supposedly been making eyes at Howell's girlfriend.

- ^ Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 101.

- ^ a b Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, pp. 225-226.

- ^ Official recordings of these bands would not emerge until more than 30 years later on Wazoo (2007) and Imaginary Diseases (2006), respectively.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 231.

- ^ "Frank Zappa > Charts and Awards > Billboard Albums". Allmusic.com. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "Apostrophe ('). Review". Allmusic.com. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ^ Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 106-107.

- ^ a b Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, pp. 114-122.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 248.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 250.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 253; pp. 258-259.

- ^ Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 131.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 261.

- ^ Slaven, Neil (2003). Electric Don Quixote: The Definitive Story of Frank Zappa. London: Omnibus Press. pp. p. 248. ISBN 0-711-99436-6.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 267.

- ^ It remains debated whether Zappa had conceived the material as a 4-LP set from the beginning, or only when approaching Mercury-Phonogram; see, e.g., Watson, 2005, Frank Zappa. The Complete Guide to His Music, p. 49. In the liner notes to the 1996 release, however, Gail Zappa states that “As originally conceived by Frank, Läther was always a 4-record box set.”

- ^ Watson, 2005, Frank Zappa. The Complete Guide to His Music, p. 49.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 261.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 262.

- ^ In 1978, Zappa served both as host and musical act on the show, and as an actor in various sketches.

- ^ Zappa, Frank, 1978, Zappa in New York, Liner Notes.

- ^ Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 132.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 261-262; Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 134.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 234.

- ^ Swenson, John (March 1980). "Frank Zappa: America's Weirdest Rock Star Comes Clean". Retrieved 2008-01-04.

- ^ Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 138.

- ^ a b Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 140.

- ^

Groening, Matt; Menn, Don (1992), "The Mother of All Interviews. Act II: Matt Groening joins in on the scrutiny of the central decentralizer", in Menn, Don (ed.) (ed.), Zappa! Guitar Player Presents., San Francisco, CA: Miller Freeman, p. p. 61, ISSN 1063-4533

{{citation}}:|editor-first=has generic name (help);|page=has extra text (help) - ^ Both albums made it onto the Billboard top 30. "Frank Zappa > Charts & Awards > Billboard Albums". Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ a b "Frank Zappa > Charts & Awards > Billboard Singles". Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 234.

- ^ Peterson, Chris (November 1979). "He's Only 38 and He Knows How to Nasty". Relix Magazine. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ "Have I Offended Someone by Frank Zappa". Rykodisc. May 1997. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ^ a b Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 140.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 277.

- ^ Watson, 2005, Frank Zappa. The Complete Guide to His Music, p. 59.

- ^ Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, p. 180.

- ^ Watson, 2005, Frank Zappa. The Complete Guide to His Music, p. 61.

- ^ Baby Snakes, 2003, DVD cover, Eagle Vision.

- ^ a b Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 282.

- ^ Sohmer, Adam (2005-06-08). "Baby Snakes – DVD". Big Picture Big Sound. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ a b Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 161.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 284.

- ^ Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 165.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 283.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "You Are What You Is. Review". Allmusic.com. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ a b Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, pp. 169-175.

- ^

Zappa, Frank (November 1982). "Absolutely Frank. First Steps in Odd Meters". Guitar Player Magazine. p. 116.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Swenson, John (November, 1981), Frank Zappa: Shut Up 'N Play Yer Guitar, Shut Up 'N Play Yer Guitar Some More, The Return of the Son of Shut Up 'N Play Yer Guitar, Guitar World

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Huey, Steve. "Valley Girl. Frank Zappa. Song Review". Allmusic.com. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ a b Lowe, 2006, The Words and Music of Frank Zappa, p. 178.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 304.

- ^ a b Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, pp. 146-156.

- ^ Ocker, David (November 1994). "The True Story of the LSO". Zappa & Other Music Resources Index. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Ruhlmann, William. "London Symphony Orchestra, Vol. 1. Review". Allmusic.com. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ a b c Zappa with Occhiogrosso, 1989, The Real Frank Zappa Book, pp. 172-173.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 319.

- ^ Watson, 2005, Frank Zappa. The Complete Guide to His Music, p. 73.

- ^ The musical was eventually produced for the stage in 2003. See "Thing-Fish - The Return of Frank Zappa". Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^

Carr, Paul; Hand, Richard J. (2007), "Frank Zappa and musical theatre: ugly ugly o'phan Annie and really deep, intense, thought-provoking Broadway symbolism", Studies in Musical Theatre, 1 (1): 44–51, doi:10.1386/smt.1.1.41_1

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Record Labeling. Hearing before the committee on commerce, science and transportation". U.S. Government printing office. 1985-09-19. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ CNN (1986). Crossfire with Frank Zappa and John Lofton (TV debate). YouTube. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ^ Nuzum, Eric. "Censorship Incidents: 1980s". Parental Advisory: Music Censorship in America. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 346-350.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 348.

- ^ Nolan, David F. (January 1994). "Libertarian Zappa dies". LP News Archive. Retrieved 2007-11-15.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 340.

- ^ For a comprehensive comparison of vinyl of CD releases, see "The Frank Zappa Album Versions Guide – Index". Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, pp. 357-361.

- ^ a b Freeth, Nick (2001). Great Guitarists. UK: Bookmart Limited. ISBN 1 84044 093 7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 369.

- ^ Miles, 2004, Frank Zappa, p. 371.

- ^ Slaven, 2003, Electric Don Quixote, p. 386.

Further reading

- Courrier, Kevin (2002). Dangerous Kitchen: The Subversive World of Zappa. Toronto: ECW Press. ISBN 1-55022-447-6.

External links

- Frank Zappa

- The Mothers of Invention members

- Experimental musicians

- Experimental composers

- 1960s music groups

- Pre-punk groups

- American composers

- American rock guitarists

- American jazz guitarists

- American rock singers

- American songwriters

- American multi-instrumentalists

- Censorship in the arts

- Sicilian-Americans

- Italian-American musicians

- 20th century classical composers

- American satirists

- American experimental filmmakers

- American atheists

- Grammy Award winners

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees as a Performer

- Hollywood Walk of Fame

- Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame inductees

- American humanists

- Free speech activists

- People from Harford County, Maryland

- People from Baltimore, Maryland

- Maryland musicians

- California musicians

- Prostate cancer deaths

- 1940 births

- 1993 deaths