On December 10, 1836, the Georgia legislature granted a charter to Emory College, named for the young Methodist bishop John Emory, from Maryland, who had died in a carriage accident the previous year. Not until two years after the chartering would the College open its doors, and on September 17, 1838, the College's first president, Ignatius Alphonso Few, and three other faculty members welcomed fifteen freshmen and sophomores. They hailed from as far away as Charleston, South Carolina, and they included a future Emory president, Osborn L. Smith, and a future member of the faculty, George W. W. Stone.

In retrospect, the mission of the nineteenth-century college appears to have been to rein in the spirit as much as to expand the mind. Certainly that was true at Emory. Students had to be in their rooms during study hours and could not go beyond the town limits more than a mile without the president's consent. Signing their names into the Matriculation Book, the earliest students bound themselves to obey the "Laws and Statutes of the College." Despite the watchful attention of their "guards," students often found ways to work up enough mischief for the faculty to put them on probation, even to expel them. Covington, an apparent seedbed of temptation, provided the allure of taverns and traveling shows.

Other social outlets proved more harmonious with the academic tenor of the campus. Two principal venues for student gatherings were Phi Gamma Hall and Few Hall, named for the two literary societies that brought students together for sharing meals, preparing their lessons, and talking about matters of the intellect. A keen competitiveness developed between the two societies, leading to a tradition of debate that permeated the campus, and laying the groundwork for Emory's national preeminence in debate-a tradition carried forward since 1955 in the Barkley Forum.

Athletics, too, has had an important place at Emory for well over a hundred years-although Emory has never played intercollegiate football and still proudly proclaims, under the emblem of a football on T-shirts, "Undefeated Since 1836." For many years, going back to the presidency of Warren Candler in the 1890s, Emory prohibited intercollegiate sports. His principal objection was the cost of intercollegiate athletics programs, the temptation to gambling, and the distraction from scholarship. Candler was not unalterably opposed to athletics, however. During his presidency he oversaw the creation of the nation's first model intramural program. In spirit the program made it possible for every student to participate in athletics, and this possibility became at Emory a guiding principle-"Athletics for All."

Athletics, too, has had an important place at Emory for well over a hundred years-although Emory has never played intercollegiate football and still proudly proclaims, under the emblem of a football on T-shirts, "Undefeated Since 1836." For many years, going back to the presidency of Warren Candler in the 1890s, Emory prohibited intercollegiate sports. His principal objection was the cost of intercollegiate athletics programs, the temptation to gambling, and the distraction from scholarship. Candler was not unalterably opposed to athletics, however. During his presidency he oversaw the creation of the nation's first model intramural program. In spirit the program made it possible for every student to participate in athletics, and this possibility became at Emory a guiding principle-"Athletics for All."

In time, the Board of Trustees modified its position on intercollegiate sports by reaffirming the ban on major sports-football, basketball, and baseball-but allowing the possibility of competition in others. Soon Emory was competing in soccer, swimming, tennis, track and field, and wrestling, and in 1985 Emory helped to found the University Athletic Association, a league of Division III members that stresses academics first. Emory's intercollegiate programs regularly rank among the top ten NCAA Division III programs in the country and graduate more academic all-Americans than any other university in Division I, II, or III.

For the first half-century of its life Emory struggled for existence, clinging to a tenuous financial lifeline. When war broke out between North and South in 1861, every student left to fight, and the College's trustees closed the College for the duration. When Emory reopened in January 1866, three faculty members (including President James Thomas) returned to a campus whose buildings had been used for military hospitals and whose libraries and equipment had been destroyed.

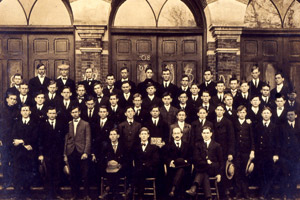

By the turn of the twentieth century, Emory's curriculum had evolved from a traditional liberal arts program dependent on rote memorization and drill, to become broad enough for students to earn degrees in science, to study law or theology, and even to pursue learning and expertise in technology and tool craft. President Isaac Stiles Hopkins, a polymath professor of everything from English to Latin and Math, had launched a department of technology that struck the fancy of state legislators, and soon enough they were luring him away from Emory to become the first president of what is now the Georgia Institute of Technology.

By the turn of the twentieth century, Emory's curriculum had evolved from a traditional liberal arts program dependent on rote memorization and drill, to become broad enough for students to earn degrees in science, to study law or theology, and even to pursue learning and expertise in technology and tool craft. President Isaac Stiles Hopkins, a polymath professor of everything from English to Latin and Math, had launched a department of technology that struck the fancy of state legislators, and soon enough they were luring him away from Emory to become the first president of what is now the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Still, the sleepy little town of Oxford offered little advantage to a college whose trustees might have their visions set on higher aspirations. By happenstance, the road from Oxford to Atlanta was paved by Vanderbilt University. In 1914, following a protracted struggle between the Vanderbilt University Board of Trust and the bishops of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, over control of the university, the church severed its long relationship with Vanderbilt and made plans to create a new university in the Southeast. Asa Candler, the founder of The Coca-Cola Company and brother to former Emory President Warren Candler, helped the church decide that the new university should be built in Atlanta. Writing to the Educational Commission of the church on June 17, 1914, Candler offered $1 million and a subsequent gift of seventy-five acres of land.

Emory College trustees agreed to move the college to Atlanta as the liberal arts core of the university. Those seventy-five acres, about six miles northeast of downtown Atlanta, lay in pasture and woods amid Druid Hills, a parklike residential area laid out by landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead, the designer of New York City's Central Park. Within a year marble buildings were under construction out in the Druid Hills, and within four years-by September 1919-Emory College had joined the schools of theology, law, medicine, business, and graduate studies at the University's muddy new campus.

Emory College trustees agreed to move the college to Atlanta as the liberal arts core of the university. Those seventy-five acres, about six miles northeast of downtown Atlanta, lay in pasture and woods amid Druid Hills, a parklike residential area laid out by landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead, the designer of New York City's Central Park. Within a year marble buildings were under construction out in the Druid Hills, and within four years-by September 1919-Emory College had joined the schools of theology, law, medicine, business, and graduate studies at the University's muddy new campus.

The course of Emory's history changed dramatically and forever when, in November 1979, Robert Woodruff, an Emory alumnus and former Coca-Cola chairman, and his brother, George, transferred to Emory $105 million in Coca-Cola stock (worth nearly one billion dollars in 2005). At the time the largest single gift to any institution of higher education in American history, the Woodruff gift made a profound impact on Emory's direction over the next two decades, boosting the University into the top ranks of American research universities. In the quarter-century since, Emory has built on its considerable strengths in the arts and humanities, the health sciences, and the professions, through strategic use of resources.

The small community of scholarship founded in Oxford has grown, but Emory's growth in research has in no way diminished the insistence on great teaching by the faculty. The 1997 report of the University Commission on Teaching reaffirmed Emory's historical emphasis on the high quality of teaching at all faculty levels and in all schools and recommended various means of support to ensure the perpetuation of this great tradition.

Since September 2003 the University has undertaken to refine its vision for its future and to develop a strategic plan for how to get there. The Vision Statement calls for Emory to be

In 1836, when the Cherokee nation still clung to its ancestral lands in Georgia, and Atlanta itself had yet to be born, a small band of Methodists dedicated themselves to founding a new town and college. They called the town Oxford, linking their little frontier enterprise with the university attended by the founders of Methodism, John and Charles Wesley. The college they named Emory, after an American Methodist bishop who had inspired them by his broad vision for education that would enhance the character as well as the mind of men and women.