On Valentine’s Day, the New York Times puzzle known as Spelling Bee gave me the gift of annal.

Until that historic moment, the online puzzle had recognized the plural, annals, but not the singular. Anal, too, was fine; Spelling Bee, while hostile to vulgarity, allows nonpejorative descriptions of anatomy.

The man who crafts this daily puzzle, Sam Ezersky, is still ambivalent about annal, and says its longtime ban generated more complaints than any other word in the puzzle’s history. “I dug my heels in for so long on this one, because, really, you never would use the familiar ‘annals’ in the singular,” he told me via email.

I would argue that annal is more likely to be used than attar, hondo, tori, torii, nene, and abbacy, just a sampling of the words that have eluded me in the past six months that I have been working the Bee on a daily basis. But who am I to challenge Ezersky, a 24-year-old puzzle prodigy who has deemed naan and raita acceptable, but not chaat?

Hi, I’m Laura and I’m a Spelling Bee obsessive.

Like a lot of aging Americans—I’m 61—I have heard that puzzles and word games may stave off cognitive decline. Alas, I don’t enjoy most of them. Scrabble annoys me; I can’t trust a game in which a well-played za scores more points than, well, abbacy. I’m capable of solving crosswords if I hunker down, but they require more time than I have to spare on weekdays.

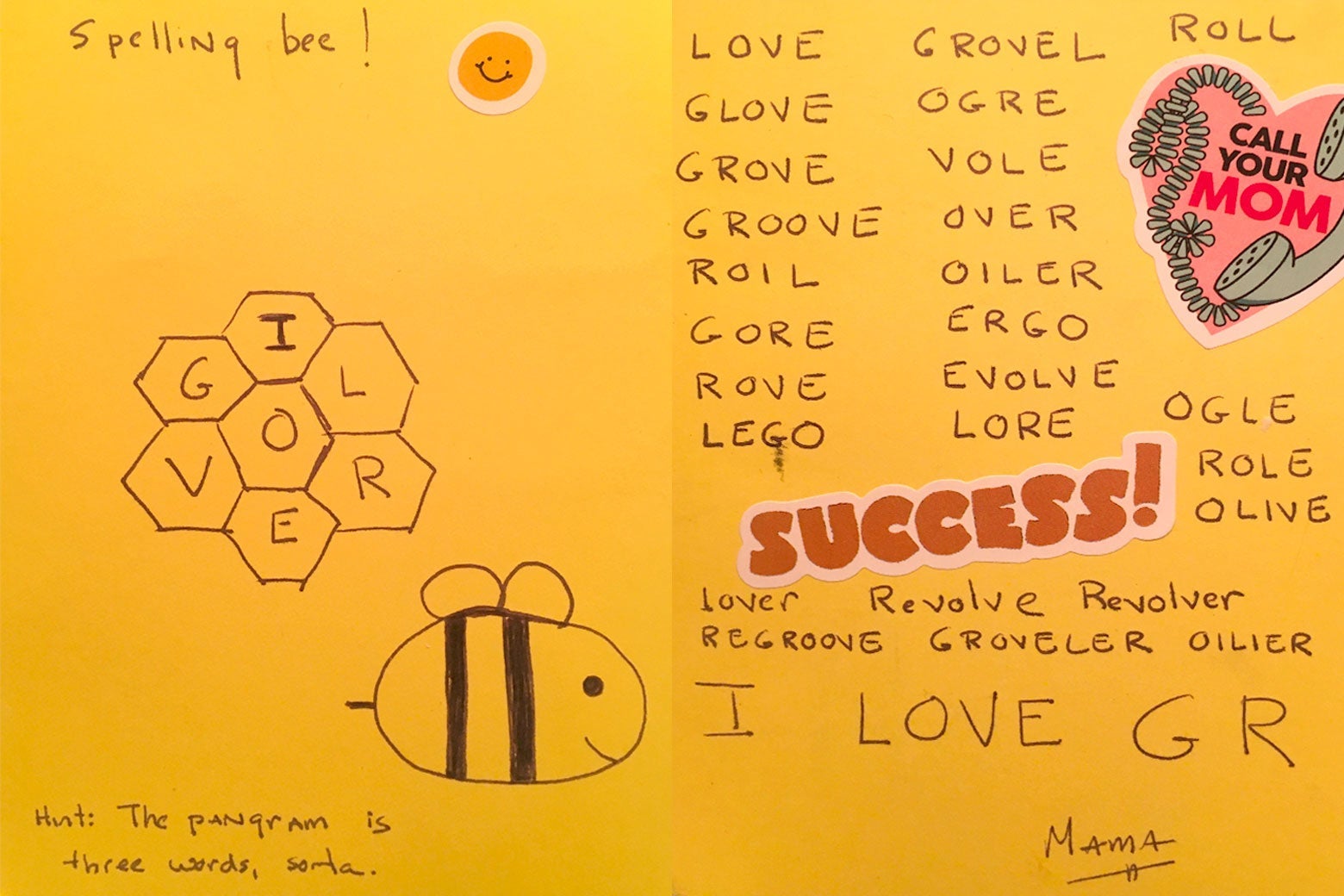

Spelling Bee, however, is perfect, a sort of no-holds-barred Boggle, minus the time limit. Every day, it’s made up of seven letters, six of which surround a central letter. Because each letter is encased in a hexagon, the visual effect is hivelike. The goal is to make as many so-called common words as you can, using the letters as often as you like—as long as the central letter appears at least once in each word and each word is at least four letters long.

The print version of Bee, which appears in the New York Times Magazine, plays by slightly different, stingier rules than the online game, which is probably why no one cares about the print Bee. The online version is practically Pavlovian, awarding each discovery with a chirpy adjective (“Nice!” “Awesome!”) and showing one’s virtual progress through nine levels per day, from “Beginner” to “Genius.” The best moment, by far, is bagging a pangram, a word that uses all seven letters. You get 14 points for that sucker, while only one point for a four-letter word, five points for a fiver, etc.

Spelling Bee was the brainchild of crossword god Will Shortz, who then asked Frank Longo—whom Ezersky describes as an “unsung hero of the ‘crossworld’ ”—to create the weekly version that began appearing in the magazine in February 2015. It went online May 9, 2018, but I didn’t discover it until last summer, when I searched for a digital version in a fit of boredom. It was October before I realized how many of my Twitter friends shared my daily obsession, and how many others could be converted by my incessant Bee talk. A lot of these people also happen to be part of what is sometimes called “Book Twitter,” a loose connection of people who are trying (and even sometimes succeeding) to write books. This makes sense. When you spend your workday failing to make words do what you want them to do, staring at G A C E H L N and suddenly seeing “ganache” is a sweet victory. Discovering the pangram—”challenge,” in this case—feels like a colonic for my neural pathways.

Bee can also be social. One of my Twitter friends works it with his sons on the subway, and others will drop a hint when I get stuck, or fume with me at the puzzle’s idiosyncrasies. I especially like luring friends into the hive. So far, the only person who doesn’t seem to care for Spelling Bee is my husband, a sudoku loyalist.

My favorite Bee confederate is Abe, the 12-year-old son of my tennis partner. Abe noticed the game in the Times Magazine but had been unable to hook his mother until I introduced her to the digital version. Now he starts Bee most mornings on her phone and once made his own elaborate version for the first night of Hanukkah.

It’s a rare morning that I don’t allow myself five to 10 minutes with Bee upon waking; it’s my personal superstition that the first word one finds is a harbinger for the day. (I started with marina today; I’m not sure what that means.) I then make my daughter’s lunch, complete with an over-the-top-note, but that still gives me about 30 minutes to work Bee until I have to get her up. My goal is to hit “Amazing” by 7 a.m., which allows me to circle back to the puzzle all day, pick, pick, picking until I hit “Genius.” Only a lack of time ever causes me to surrender; I have kept the puzzle open in my tabs to keep working it for several days. (I work Bee across all my devices—phone, tablet, laptop—but prefer my laptop.)

Lately, the game seems a little harder, with fewer “gimmes”—the inclusion of S, or L, with Y, which makes it easy to build on the words one finds. But I also think each player vibrates to different letter combinations. I find myself utterly flummoxed by X’s, but I seem to fly through puzzles with G’s. Compound words are my kryptonite, and I am baffled that slangy words, such as wanna and dunno, are allowed, but profanity is not. (I have petitioned for the inclusion of the word cooch. I have been politely denied.)

One thing that nags at all Bee obsessives is the question: Are there other words out there? I asked Ezersky how he can be sure each daily word list is complete (there was quite a kerfuffle when, on Jan. 31, clickbait, a pangram, was not recognized): “I am never 10,000 percent sure. My poor girlfriend knows that the very last thing I do before bed is check the next day’s word list one last time. … Incidents like the unintentional omission of CLICKBAIT give me nightmares.”

Still, all was relative bliss in my hive world until someone let a dark secret slip: Although the online Bee does not reveal the total number of words or points possible, it will anoint you “Queen Bee” if you find every word on its list. This came to light on Jan. 1, when, on Twitter, a New York Times reporter asked for help with the pangram (gazpacho, it was a tricky one) and the New York Times Book Review editor mentioned that, even with the pangram, she was short of Queen status, noting that another Times editor achieved perfection almost every day.* Queen status! Perfection! Most of us “Geniuses” didn’t even know that was possible!

Queen Bee definitely messed with my head. I found myself shooting for it on weekends and long trips. A friend advised me to stop, saying it ruins the game. He’s right. While it’s fun to share a screen grab of the announcement that you are Queen Bee for a day, I always—humblebrag—feel a little empty when I queen. So I’ve tried to become content with what my friend calls “minimal genius,” although I really wish she would stop calling it “minimal genius.”

The best thing about Bee is that another one comes along every day, at 3 a.m. EST.* Don’t ask me how I know. Some days are easy—I’ve been known to achieve “Genius” before I even get out of bed, making me absolutely insufferable all day—but others are hard and confounding, which I guess makes Bee a lot like life. More like life than sudoku and KenKen at any rate.

Correction, Feb. 19, 2020: This article originally stated that, on Jan. 1, a New York Times reporter tweeted about being short of Queen status. It was the New York Times Book Review editor who was short of Queen status.

Correction, Feb. 21, 2020: This article originally stated that a new Bee is released every day at 4 a.m. It is released every day at 3 a.m. EST.