Is it possible that Elvis Presley’s most significant and pioneering contribution to our culture has remained largely unremarked upon?

The most important aspect of Elvis’ legacy is something so obvious that it has defied revelation.

Elvis Presley, who would have turned 81 this week, did not invent rock ’n roll. He wasn’t the first recording artist to play electric hopped-up hillbilly music, nor the first to blend Appalachian howls and inner city r&b; and he certainly wasn’t the first Caucasian man (or woman) to “sound” like a black person. On top of that, Elvis was neither a composer nor a conceptualist, so his gifts didn’t lie in that domain. Yet Elvis Presley is one of the defining figures in the age of electric, as he should be.

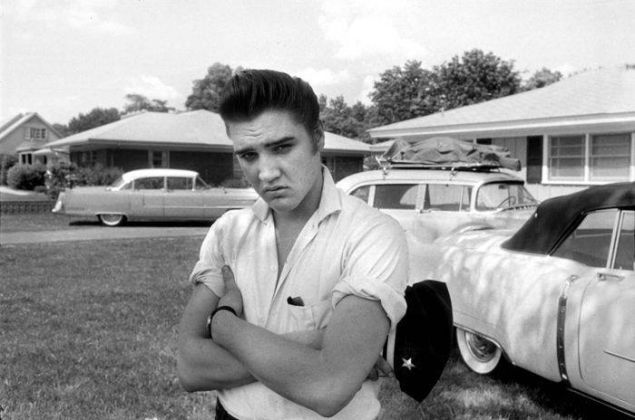

The most important aspect of Elvis’ legacy is something so obvious that it has defied revelation: Elvis Presley invented androgyny as the standard template for the rock/pop frontman. Elvis did not succeed because of the myth that he was the first white boy who sang like a black man. Elvis succeeded because he was the first white boy singer who looked like a pretty white girl.

In the 62 years since Elvis debuted, we have become so used to the idea that pop stars are pouting man-girls that sexual ambiguity and rock ’n roll have become virtually synonymous.

Think of Jim Morrison, Mick Jagger and all those other narrow, serpentine singers with pregnant lips and lissome hips; consider the doe-like, heart-shaped face of Paul McCartney; visualize, in your head, Botticellian Mark Bolan or Michael Stipe and 88,000 others. We are so accustomed to this androgyny that it’s a bit hard to believe that the concept once didn’t exist.

Pre-Elvis singers might have been handsome, but nobody outside of the eccentricities of vaudeville displayed femininity, or looked pretty and male. Before Elvis, Caucasian male vocalists, band leaders, and pop stars were wiry, beefy, bovine, beaming, brilliantined, priestly, aquiline, avuncular, handsome, lantern-jawed, gawking, owlish, occasionally even fey; and in the realm of hillbilly music, they were either doughy or carried the withered, sunken, accusing faces you see in old Civil War photographs and Walker Evans portraits.

But none had been pretty like a girl, and certainly none had combined such a look with an absolutely assured male presence that was virtually palatable in every photo or recorded yelp and hiccup.

Elvis was the prototype for the look of rock ‘n roll.

The lasting impact of the cultural tsunami triggered by Elvis the Pretty was gigantic. Elvis was the prototype for the look of rock, and by that, I don’t mean the obvious rockabilly rebel pose or ghoulish quiff. By introducing that gender bend via his uniquely sylphlike presence and asserting that the masculine and the feminine, bundled up in one lithe and saucy package, could sell sex and song, Elvis announced that the rock-age rebellion, the break from the past, would not just be musical, but sexual. By integrating the feminine into the mainstream pop cultural vocabulary, Elvis drew the line in the sand that identified the battleground for the future culture wars.

The spirit of the 1960s begins when Pretty Elvis bursts onto the consciousness of mainstream America in 1954-56. From that moment forward, from the first stutter that lanced from Elvis’ lopsided, louche, feral and feline lady-lips, it would be freaks vs. straights. The delineation of the Shirts and the Skins in the culture wars would not have been possible without Elvis’ absolutely brilliant and adamantly natural ability to be a true man and a true man-girl, at the same time, in the same body.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eGaXbRqZOAs&w=420&h=315]

Likewise, although Elvis’ shivering, shimmering frantic hillbilly antics are deeply compelling, the most startling aspect of his early work is his barely-there ballads, minimal, muscular but vulnerable songs that defy any contemporary trend.

“Blue Moon” and “I Don’t Care If The Sun Don’t Shine,” both from his legendary Sun catalog, are forged with a feminine touch and masculine power. These are halo’d shadows of songs, recordings so reduced that they are almost terrifying. Truly shocking when listened to now, these songs have an impact that none of his “faster” Sun recordings (with the possible exception of “Mystery Train”) achieve. Elvis strips these songs of any corn, studio affectation or commercial aspiration; all that’s left is the ancient and modern heart of the balladeer and the sense of loss to be found in famine, migration, heartbreak and poverty.

These ghostly Sun ballads evoke the same feeling you get when you listen to hissing 78s of the Carter Family, Sid Hemphill, or Amede Ardoin; at the same time, they are almost frighteningly modern, as they conjure the stripped, ripped and raw cavernous purity of Suicide, Mazzy Star, Moondog and Springsteen’s Nebraska.

Now, Elvis isn’t as big as he used to be.

There are a lot of reasons for this, and these are just some of them: The mainstreaming of country music in the post-Garth Brooks Era (Brooks was the first country artist to benefit from Soundscan, which, for the first time, accurately reported the economic power of country music) eliminated the need for a single figurehead who embodied the hopes and affections of non-urban, non-pop/rock America; sloppy catalog releases have made Elvis’ music far less sensibly accessible to the public than it should be; and finally, the exploitive and un-strategic manner in which Elvis’ career was handled in his life (and his legacy was handled posthumously) means that the extraordinary highs of his latter work are not spotlighted, and pieces like “American Trilogy” (an important musical statement and devastating performance that needs to be held favorably alongside the best work of Leonard Cohen, Tim Buckley, Elliot Smith, Kurt Cobain, Patti Smith, or Scott Walker ) is consigned to the kitsch-bin.

All of these elements (underlined by the fact that the 1980s’ ubiquity of MTV favored and promoted the interests of archival artists like the Beatles and Zeppelin but virtually ignored the formerly omnipresent Elvis, for reasons too lengthy to be detailed here), combined to make someone who was virtually synonymous with the rock genre prior to 1980 virtually marginal to it after 1990. As late as, say, 1979, it was unimaginable that you would have a generation of music fans—knowledgeable or casual—who barely gave a shit about Elvis. But sadly, that’s the case.

And I miss him. And it’s time to reconsider him and honor him for what may have been his greatest achievement: He is the father/mother of the feminine in rock. It was the gender blend/bend pioneered by Elvis that made rock what is—the language of the anthem of all outsiders.

(Many thanks to Louis Maistros, Matthew Goodman, Nancie S. Martin, and most of all the late, great John Loscalzo for helping me work out some of these ideas.)