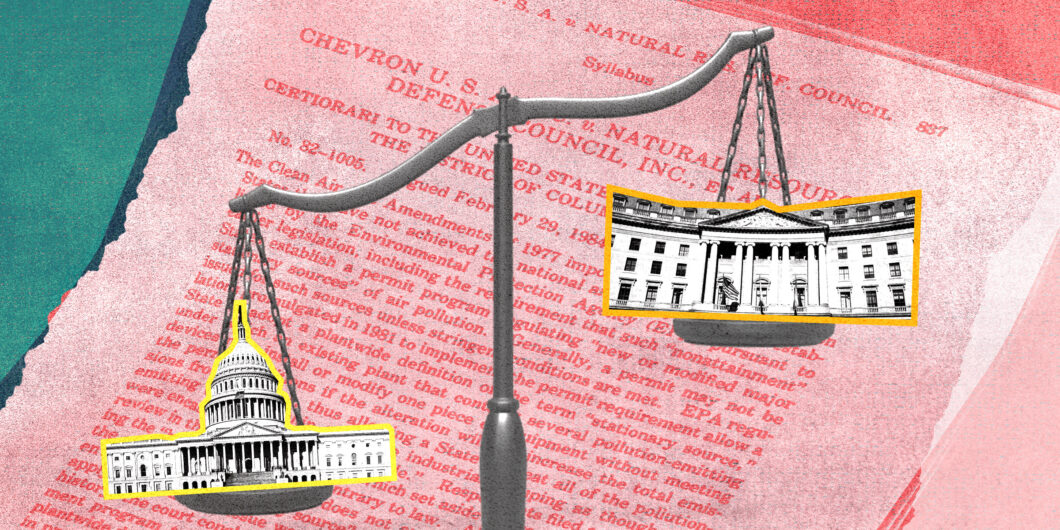

After Chevron, an Ambiguous Future?

After Justice Scalia died in 2016, I wrote a short essay about his approach to administrative law, which was both principled and prudential. Scalia put the point well in his DC Circuit days: “Resolving the tension between the rule of law and the will of the people—between law and politics—is the supreme task of our government system,” he wrote for the Journal of Law and Politics.

“We sometimes tend to forget that it is more a matter of resolving tensions than of drawing lines, for there is no clear demarcation between the two,” he continued. “Laws are made, and even interpreted and applied (by administrative agencies), through a political process; and politics are conducted under the constitution and statutory constraints of the law.”

Accordingly, the task for administrative law, as he saw it, is to vindicate the Constitution’s structure and our statutes’ sometimes ambiguous words, and to arrange each institution’s own incentives towards that end. My essay in this forum was meant to take a similar approach, thinking hard about the incentives that a post-Chevron future might create for Congress, agencies, and courts.

Of course, sometimes things work out much differently than one originally expected. Chevron exemplifies this: in the courts, agencies, and Congress, administrative law played out much differently than Scalia originally hoped. Eventually, Scalia himself concluded that a recalibration was needed, as both his son Eugene Scalia and friend Ronald Cass have written.

Accordingly, when making institutional predictions, one needs a major dose of humility. And my respondents offer more than enough reason to suggest that the possible scenarios that I sketched out will not come to pass, in any of the three branches of government.

First, the courts: Professor Walker warns that ending Chevron would force judges to carry out a near-impossible task of interpreting ambiguous statutes without political bias. “In a world without Chevron, one would expect judges to find it harder to separate their judging from their politics,” he writes. “Either the law runs out, or the best reading of the statute is that Congress has delegated broad policy discretion to the agency.”

There is an echo of Scalia’s original case for Chevron here: pre-Chevron judges often micromanaged agencies’ policy discretion under vague statutes, and Chevron was intended to get judges out of the policy business. But then again, Scalia himself expected that textualist judges would see many statutes as much less ambiguous than other judges would. Perhaps the pre-Chevron trend toward judges confusing law-interpretation and policy-making will be less pronounced in an era when, I’m told, “we’re all textualists now.”

Yet Chevron’s framework already embodies a major risk of policy-based disagreements, in the pivotal question of whether a statute is ambiguous or not. As Justice Kavanaugh warns, “Judges often cannot make that initial clarity versus ambiguity decision in a settled, principled, or evenhanded way.” Reducing Chevron deference might trade one risk factor for the other—moving from disagreements over whether a law is ambiguous to disagreements over what a law means. If so, then I’ll be interested to see whether administrative law disagreements reflect disagreements over policy or textualism—or both.

If a post-Chevron judiciary might have to spend more time scrutinizing agencies’ assertions of “expertise,” then it follows that Congress would have more reason to focus its own oversight hearings on the same question.

Professor Walker also warns about another negative consequence in the courts: great disuniformity in the law when different courts disagree over whether an agency’s legal interpretation is lawful or not. It’s a fair point, as I cautioned in my initial essay: Chevron made the law more uniform across all courts at any given moment in time. But it also made the law less uniform over time, as administrations flip-flopped their legal interpretations. Even Scalia, who generally welcomed agency flip-flops in his original Chevron article, warned that too many flip-flops could raise serious problems: “At some point, I suppose, repeated changes back and forth may rise (or descend) to the level of ‘arbitrary and capricious,’ and thus unlawful, agency action.” I suspect this problem proved far worse than Scalia expected, in terms of the havoc that Chevron would wreak over time; in any event, that instability strikes me as far more harmful than courts’ short-term disagreements over an agency’s new interpretation.

Turning to the agencies, Professor Greve is skeptical that reducing deference would actually spur agencies to improve their legal analyses. “Possibly,” he offers, but “then again, they may further immunize their actions against judicial control.” Surely that is a major risk. We’ve long seen agencies bristle under even the fairly gentle requirements of notice-and-comment rulemaking, moving more toward “guidance documents” or the even more nebulous tools of financial regulation. (I’ve tried to coin a phrase for this, the “passive-aggressive administrative state.”)

I don’t think I’m unreasonable to suggest that greater judicial scrutiny of agency rules might improve the rulemaking process—see, for example, current OIRA Administrator Richard Revesz’s new article urging agencies to adapt to the Major Questions Doctrine—but Professor Greve’s word of caution, like Professor Walker’s, is well-taken. As I note in my opening essay, a post-Chevron era might become more skeptical of the administrative process in general, particularly as to agencies’ claims of expertise. I suspect that this skepticism would extend to agencies’ efforts to avoid judicial review—indeed, we’ve already seen that skepticism in cases like Sackett I—and skeptical judges would benefit immensely from the work of scholars like Kristin Hickman and Nicholas Parrillo on questions of how binding an agency’s action might actually be, and thus when judicial review is available.

Finally, on Congress, Professors Greve and Walker administer a few more doses of humility and pessimism. But Professor McGinnis is more hopeful, even optimistic. He writes that “eliminating Chevron would also help change our political culture by reducing political polarization,” because “without Chevron, partisans—and thus their representatives—would feel more need to compromise on a more determinate law, because they cannot get all they want by subsequent agency interpretation.” I agree completely; in 2019, I wrote a brief note warning that Chevron-era flip-flops were an enormous contributor to Congress’s own decline, because “the availability of unilateral presidential action mitigated the hydraulic forces that might otherwise press members of Congress to compromise on a legislative solution.” Professor McGinnis’s full law review article on this point, with Professor Michael Rappoport, is tremendous.

My initial essay spent a lot of words on Congress, but I can’t help but add one more point about the Constitution’s first branch in a post-Chevron era. If, as I suggest, a post-Chevron judiciary might have to spend more time scrutinizing agencies’ assertions of “expertise,” then it follows that Congress would have more reason to focus its own oversight hearings on the same question. If the Supreme Court’s Relentless and Loper-Bright decision offers greater deference to agencies’ genuine exercises of expertise, then I suspect that congressional committees will use their hearings and subpoenas to probe the agencies’ policymaking process, partly for Congress’s own legislative (and political) purposes, and partly to aid litigants bringing lawsuits against major agency actions.

But that prediction, like those in my first essay, is just a guess. And as I warned at this forum’s outset, the full effect of Relentless and Loper-Bright won’t be known until years after this summer’s upcoming decision. We’ll have much to write about!

I’ll look forward to future Law & Liberty forums—and I’m grateful to the editors, and my thoughtful respondents, for this one.