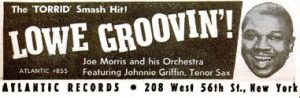

Joe Morris: “Lowe Groovin”

27 Thursday Apr 2017

Written by Sampson

Tags

No tags :(

Share it

Atlantic Records official website has a vast index of artists, past and present, for visitors to peruse, with individual pages offering some related articles, a link to the artist’s own website if applicable, a listing of some of their albums, song playlists, and for current acts a schedule of upcoming concerts. It might sound like a lot but truthfully it’s kind of skimpy in terms of content, but the collection of artists itself is pretty damn impressive befitting the label’s legendary history.

However, missing from that roll call of nearly 200 names is Joe Morris, without whom there’d BE no Atlantic Records website, because quite simply the company itself likely would not have survived into the 1950’s, let alone the 21st Century.

For all intent and purposes it was Morris who gave them much needed artistic credibility and consistent sales when they were starting out, enabling them to stay afloat long enough to find their niche with the emerging rock ‘n’ roll market which in turn made them all – artist and auteurs alike – far more successful than any of them ever realistically envisioned. Sadly it is doubtful that anyone drawing a paycheck from Atlantic Records nowadays would be able to tell you who the hell Joe Morris was, what instrument he played, or the names of any of his songs.

So much for gratitude.

The Beginning: The Other Side Of (The) Atlantic

So that I can’t be accused of the same neglect, though this biographical introduction shouldn’t be necessary for the type of astute music fan who makes Spontaneous Lunacy a regular stop, Atlantic Records founder Ahmet Ertegun was born Turkey to a lawyer who soon became a trusted figure in the country’s new nationalist government. In time the elder Ertegun was made an ambassador, first to Switzerland, then in succession to France, Great Britain and finally America, where in 1935 he took his family, eldest son Nesuhi and younger son Ahmet among them, to live a life of privilege in Washington D.C.

Having been turned on to jazz in England, Nesuhi and Ahmet immersed themselves in music once in the United States. Ahmet was already shaping up to be a walking contradiction. Highly-educated and with a lifelong taste for elegance, he also possessed uncanny street-smarts acquired in part by his restless curiosity for the bohemian lifestyle. He and Nesuhi soon were inviting famous jazz musicians to the Turkish Embassy, first dining with them and then to listen to them jam. This elicited the outrage of a southern senator who complained about the scandalous buzz they were creating by having Negroes as honored guests who entered the embassy through the front door no less, a definite social faux-pas for the pre-Civil Rights enlightened America. The reply to the bigoted senator by the Ertegun’s father – “In my home friends enter through the front door. However we can arrange for you to enter through the back.” – was priceless.

When the senior Ertegun died during World War Two, Ahmet and Nesuhi remained in America to seek their fortune, having to sell their vast record collection after vacating the luxurious embassy mansion they’d called home for the past decade just to be able to pay for a place to stay.

Like Pulling Teeth

The contradictions that defined Ertegun’s life were never more apparent than at this point in his life. Intelligent and well-connected, but broke and with absolutely no experience holding any type of job and possessing no real marketable skills to obtain one, Ahmet knew he wanted to make records but had no idea how to go about it.

His personal assets were few, but notable. To start with his enthusiasm for, and knowledge of the music was far greater than most professional record men in the business, his comfort level with the artists, despite ethnic and class differences, was genuine, and his charm was strangely intoxicating to most and was able to get him in doors where others, perhaps far more qualified, would’ve had them slammed in their faces.

After a few false starts he hooked up with Herb Abramson, who had previously worked for National Records and thus had the requisite background to handle the more intricate details of the record business, and together they started Atlantic Records as 1947 wound down with the majority of the start-up money provided by Ahmet’s dentist.

Like most independent record companies, even in the heyday of the indie market in the 40’s, the road to success was a rocky one and Atlantic’s first year was underwhelming to say the least. Having rushed to record as many sides as possible before the recording ban went into effect the results were largely deemed unreleasable by the finicky partners Abramson and Ertegun, costing themselves thousands of dollars they didn’t have to waste on dead ends. But the two survived their first shaky year in business thanks to their jazz credentials – as fans, collectors and in a more limited sense, at least on Ertegun’s part, with the jam sessions he’d overseen with first rate jazz musicians.

The only two viable commercial artists they had their first year both came out of highly respected jazz circles and each were attempting to branch out into the largely undefined mongrel style of rock that was emerging by the end of 1947. Guitarist Tiny Grimes we’ve already met. His sides for Atlantic would be first rate productions and calling cards for the fledging company, as well as decent sellers that would result in the company’s first chart hit the following fall.

The other artist of note they signed would have an even more dramatic impact on their financial stability long term. His name was Joe Morris, a trumpeter who’d worked with the legendary Lionel Hampton, the same Hampton who Ahmet had befriended and had nearly convinced to invest 15 grand to start a record label with him before Hamp’s more practical wife shot the idea down.

It would be Morris who would generate Atlantic’s first noise-makers commercially and it’d be Morris who would record for the company well into their glory days, setting a high class standard that Atlantic would soon be known for.

Get In The Groove

Morris was a very good trumpeter but an even better bandleader. In those days few qualities in music were more respected than the ability to put together a top notch band, write and arrange their music, direct traffic in the studio and onstage and Joe Morris was among the first to bring those qualities from jazz to rock ‘n’ roll. He could oversee the proceedings and keep things moving while at the same time was perfectly comfortable – and astute enough – to let the spotlight shine a little brighter on whoever was deserving of it, in this case saxophonist Johnny Griffin, the centerpiece of his band.

In other words, he was exactly what Atlantic Records needed in their formative years – a skilled and versatile professional who could deliver quality goods suitable for any environment.

The record itself, Lowe Groovin’, exemplifies this. It was written by guitarist George Freeman whose own band performed it in Chicago clubs (under its original title The Hulk) where it was very popular with dancers making it a natural fit for Morris’s musical leanings when Freeman joined his outfit in mid-1947. The fact that Morris, not Freeman, got the writer’s credit is in fact what led to the guitarist’s departure from the band soon after this came out, thus costing Morris a vital second lead instrument that might’ve made his group even more of a threat over the next few years.

The record is certainly very solid if not exciting. A slow somewhat monotonous groove carries it along, lacking a crucial hook that would get you to actively seek it out yet still engaging enough to hold the attention of burgeoning rock audiences of the time looking for something that can get them moving.

The horns for the most part play in unison, lurching along like someone abruptly awoken from a deep sleep who’s trying to get their bearings while going through the motions of their morning routine, one they know by heart and yet aren’t always eager to undertake. As a result it’s slightly sluggish but at least moving in the right direction. Pianist Wilmus Reeves seems most awake at this point, rattling the keys to shake the rest out of their slumber.

Griffin’s sax solo a minute in is the water from the shower hitting your face, bracing but effective in what it needs to do, which is to get you to open your eyes and be more aware of your surroundings. It’s got a bit of a seductive quality to it, nothing flashy yet invigorating all the same.

The others follow suit now as it picks up the pace slightly, Reeves answers with a few showy fills and drummer Leroy Jackson rides the cymbals methodically, never letting up on that churning groove, in the process keeping your attention without demanding it.

Down Lowe

The success of the song, by far Atlantic’s biggest seller to date, was helped immeasurably by its title and its association with Jack Lowe Ender, a Washington D.C. disc jockey whose on air moniker was Jackson Lowe, and who was well-known to Ertegun from his days as a devout listener in the capital.

It was a common occurrence to name an instrumental after a popular dee-jay in hopes at least ONE radio station with a vested interest in its appeal would spin it on the air and get them some notoriety and hopefully some sales.

It didn’t always pan out that way but here’s one case where it actually worked on all accounts. Jackson Lowe used it as his theme song from there on in and the record sold well, particularly up and down the East Coast thanks to its exposure on his show. Since Atlantic had limited distribution that didn’t go much further than the east coast anyway this ensured their potential buyers were all aware of it and while Lowe Groovin’ wasn’t an official hit it certainly was the first tangible commercial success that Atlantic Records enjoyed.

What it did beyond that though was show that Atlantic Records had an ear for quality production values. Not only was it a tightly written and performed song, but the recording itself was clean, crisp, well balanced and in tune… all things taken for granted in years to come but for an untested label run by a pampered neophyte who just as well may have been doing all of this as an indulgent kick these were attributes that showed Atlantic’s standards of professionalism were in place from the very start.

They’re also exactly the type of things that musicians notice, particularly those thinking of signing with a label down the road. Morris’s own reputation was also well known amongst musicians and his presence with the company also acted as a silent inducement to others looking for a record contract that this upstart label might have something on the ball.

It’d be awhile before any of that started to really pay off, but for the time being Morris – along with Grimes – gave Atlantic Records something to build their musical reputation with as well as a foot in the door of the growing market that would transform American culture in short order and put the label on the map.

Atlantic’s impact would grow ever larger over the years and in time would dwarf that of Joe Morris, even though his career had plenty of high points still to come. He’ll be featured countless times here over the first decade of reviews before his tragic early death (at just 36) in 1958, but even with a clutch of hit singles to his name ultimately it may have been his role in helping Atlantic Records get off the ground that was his most long-lasting contribution to the musical landscape. In short, he made them credible.

Ertegun, who in interviews loved to recollect Atlantic’s early days with a few well-worn stories recounting some canny decisions that got the label their first hits, rarely if ever mentioned Morris as a lynchpin of the company, the key figure in helping to get them off the ground so they could BE in a position to earn those hits down the road.

At the time however, when this record was perhaps the only thing keeping the bank account from being empty and the lights from being turned off for failure to pay the electric bill, you wonder if he’d have been as stingy with the credit.

SPONTANEOUS LUNACY VERDICT:

(Visit the Artist page of Joe Morris for the complete archive of his records reviewed to date)