by Fred B. Nelson

Old cemeteries are the fountains from which history flows. It was with this in mindset that I drove out to the vicinity of Walnut Creek, which was a 19th century farming and supply center, located about 40 miles northwest of Prescott. It is currently the site of a US Forest Service guard station, which is operated in partnership with some local colleges. I noticed on a USFS map that there was a cemetery in the area, and I found it just off the Juniper Springs trail, about 1/4 mile up from the Walnut Creek road. Much of the cemetery has fallen into disrepair, but four graves are still well kept with legible headstones, noting dates of death between 1881 and 1897.

After noting the names shown on the headstones, I researched them in the Archives of the Sharlot Hall Museum. One of the graves was "W. T. Shook, Born Oct. 5, 1879, Died Dec. 6, 1881." In looking for information in the Archives on the last name of Shook, I came across a letter written in 1932 by William G. Shook, who, at age 92, was a resident of the Arizona Pioneer Home in Prescott. Mr. Shook’s letter mentioned that he had lost a son at a very early age. From that letter came much of the historical information contained in this article, along with other information found in the Sharlot Hall archives.

Walnut Creek was at the east end of a toll road owned and operated by Capt. William C. Hardy. The road ran from Hardyville (near the current site of Bullhead City) to "Camp Tollgate", just west of Walnut Creek, with the road ultimately continuing on to Prescott. Hardy used a crew of Hualapai Indians to maintain the toll road until the Hualapais joined the Mohave Indians in an uprising in the late 1860s. Camp Hualapai was established in 1869 by the military in order to keep the road open and generally keep the peace in the area. That camp was situated in Aztec Pass, on a mesa in the Juniper Mountains, overlooking Walnut Creek. The military camp consisted of eight companies, thus requiring a sizeable supply of farm products. Corn and other vegetables, as well as hay, were grown in the area. Mr. Shook, using a unique phonetic style of spelling in his letter, states, "Walnut Creek had become an agricultural section which furnished Mahavey (Mohave) County with ptaters (potatoes) and vegetabls, and the qality and quanty of the Walnut Creek products became famous." Camp Hualapai was abandoned by the military in 1873, but a post office was established there the same year. The name was changed to Charmingdale in 1879, but that P.O. was closed in 1880. The postmaster of the Charmingdale post office was a Mr. S. C. Rogers, who was also a teacher.

One of the other legible stones in the Walnut Creek cemetery is that of "Marilla Jean Rogers, Died March 6, 1897" – who was reportedly the wife of postmaster S. C. Rogers. The following poem is carved in a wooden plaque above her headstone: "Within this grave an angel lies, No myth that flits above the skies, A host in life of friendly ties Bespoke an angel good and wise". In 1883, Charmingdale was renamed Juniper. A post office was opened again that year, and remained under that name until its closing in 1910.

Things apparently got wild and wooly in Walnut Creek upon occasion. Mr. Shook remembered, in his own hand, "there was a herd law in those days, people had to herd or take care of their stock, or pay damages. A man named Thrasher owned a place on the northeast side of the creek and Andy Stenbrook had a place joining on the west. Thrashers horses got out of the corril and destroyed some of Stenbrook crop and Steinbrook correlled them for damages. Thrasher tracked them up and found them correled, and what transfered (transpired?) no one wil ever know. A Dutchman working for Thrasher went to hunt Thrasher and found him in the correll. Stienbrook lay with two sixshuter bullet in him and …. and Thrasher with an army model gunball through his bust."

There was another story Mr. Shook related in his letter, which is backed up by numerous old newspaper articles in the Sharlot Hall Archives. A neighbor of Shook’s, W. H. Williscraft, had leased a ranch to D.W. Dilda. Williscraft, at Dilda’s request, supplied Dilda with a hired hand named James Jenkins. Williscraft had a locked room in the house leased to Dilda, which contained some of the owner’s personal belongings. The tenant had apparently broken into the room, and taken the contents. Mr. Shook was the Justice of the Peace in Walnut Creek at the time, and advised Williscraft to see Judge Clack in Williamson Valley for a warrant, but the judge was not there, so, Williscraft went to Prescott and obtained a warrant from Judge Fleury, charging Dilda with misdemeanor larceny.

On December 20, 1885, Sheriff Mulvenon sent deputy John Murphy to make the arrest. Murphy did not find Dilda at home on the first try and returned to the nearby station. When Murphy made another attempt to find Dilda at home, but never returned to the station, a search party was formed, which later stopped at Shook’s ranch to ask questions. Shook’s wife said she had heard shots coming from the direction of Dilda’s house. Upon searching further, the group found Murphy’s horse, tied up only twenty feet from Dilda’s gate. Footprints and wheelbarrow tracks led to a nearby field. In that field, the posse found patches of blood and Jenkins’ body buried, and shortly thereafter, found Deputy Murphy’s body buried in an oat sack in Dilda’s cellar. Dilda hightailed it to Ashfork ahead of the posse. Mr. Shook’s letter continues in its unique style: "The Sherif and Party traild Dildy to Ashfork wher he had trying to get a RR ride. When the sun came up he found a place to rest on south side of a ledg of rock and was taking a sleep when he awok a lot of guns face him. It was hard for the sherif to keep the people from linshing him. Mulvenon was very popular. He gave his word that they should see him publickly hung while the posy (posse) was eating their breakfast the Sherif sliped his prisner out the back way suceeded in getting him to Prescott, where he was speedily tryed and just 30 day after the arrest he was hung wher …. Dr. Flinns addition to Prescott." Newspaper accounts tell us that Dilda was captured on December 23 (1885) near Ashfork, and was indicted by the Grand Jury on December 26, and tried, convicted, and sentenced to death on December 30. The execution was carried out on February 5, 1886, using gallows erected on the west end of Prescott. The February 6, 1886 issue of the Arizona Journal-Miner, commenting on the execution, stated, "the only incident worthy of note was the fainting of W. O. (Buckey) O’Neil of Hoof and Horn, after Dilda’s body shot through the death trap. He soon recovered from the effects, however, on the application of mild restoratives." Another eye-opener is the bill from the Yavapai County Board of Supervisors itemizing expenses of the prosecution, trial and execution of D. W. Dilda, which is shown separately. Obviously, such costs have increased exponentially since 1886.

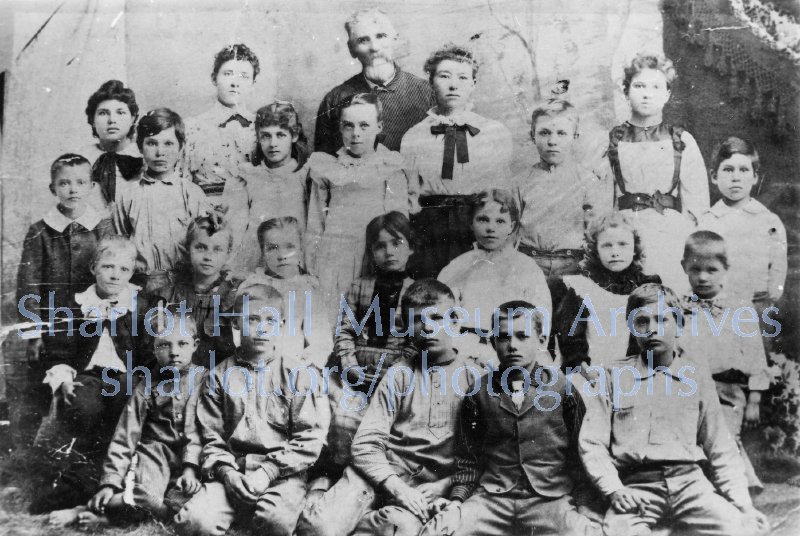

Mr. Shook also relates how he successfully operated an orchard in Walnut Creek, growing prunes, pears, apples and plums (but that the peaches didn’t make it). He goes on to state that Walnut Creek, after the last bloody incident, settled down to build a strong community and established a school population of twenty-six students. Legible names on other headstones in Walnut Creek Cemetery were: "E.D. Scholey, 1851-1881, and Roland Scholey, 1878-1881". Mr. Scholey operated a way station at Walnut Creek. An item in the March 14, 1879 edition of the Arizona Miner stated, "Mrs. Ed Scholey, who keeps a very good station at Walnut Creek, is in town. She informs us that her husband, who received, two years ago, a severe paralytic stroke, is very low and is now unable to either walk or talk." The entire Shook letter is available for reading at the Archives of the Sharlot Hall Museum, and is a real piece of Western Americana. Old cemeteries, such as the one near Walnut Creek, are more than just human remains — they are depositories of history, waiting to be discovered.

Sharlot Hall Museum Photograph Call Number:(pb086f4i5)

Reuse only by permission.

An undated photograph taken at Walnut Creek School.