Chronicles of Oklahoma

Volume 15, No. 4

December, 1937

GOVERNOR CYRUS HARRIS

By John Bartlett Meserve.

Page 373

Oklahoma has no more substantial citizenship than may be recognized among the erstwhile members of the Chickasaw Nation and

their descendants who pause this year (1937) in thoughtful regard of their exiled ancestors who emigrated from Mississippi

to the old Indian Territory, a century ago. The Chickasaws sold their lands in Tennessee and Kentucky to the United States

Government, in 1818. In consideration for this cession, the United States paid each Chickasaw enrolled at that time $1,000

annually for twenty years. Such an income in those days was considered wealth and at the expiration of the twenty years the

majority of the Chickasaws had money, lands, slaves and livestock, and to some extent an educated citizenship. The Chickasaws,

in Mississippi, lived amid comfortable environs which their own efforts through capable leadership had made possible. These

Indians had been unremitting in their fidelity to the United States Government, but finally were induced to abdicate their

hereditary domain in Mississippi to placate the surge of white settlers which was overwhelming them. The "Promised Land" lay

beyond the Mississippi.

The old Indian Territory became a traditional home of adventure wherein tribal characteristics and ambitions were to be preserved

by effective separate grouping of the Five Tribes, the members of which were guaranteed the freedom to police their own tribal

affairs. The Chickasaws had purchased a one-fourth interest in the lands in the West, obtained by the Choctaws in the

Page 374

Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, in 1830, and on arrival in the Indian Territory a joint government was organized with the

Choctaws which proved unsatisfactory as the Choctaws were in such a large majority that the Chickasaws practically had no

voice in the government. Through discerning leadership, the independent status of the Chickasaws was preserved from ultimate

absorption by the Choctaws, by the tribal agreement made with that tribe at Doaksville, Indian Territory, on January 17, 1854,

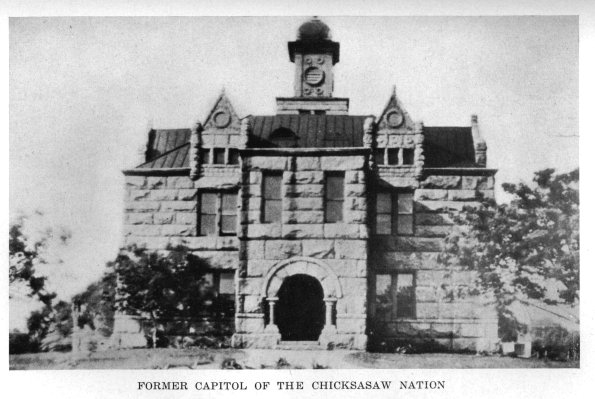

and the treaty of separation entered into at Washington, on June 22, 1855.1 To effect more completely the independent status created by these agreements, the Chickasaws, in mass convention at Tishomingo,

on August 30, 1856, adopted a formal written constitution embodying the principles of a representative form of tribal government.

This organic law, modeled after the States, was in accord with similar action previously taken by the Cherokees and the Choctaws

and to be taken by the Creeks, and was voluntarily undertaken in response to erudite leadership.2 The Chickasaws had $2,000,000 in the United States Treasury at this time from the sale of their lands in Mississippi and

as there were only about 5,000 Chickasaws enrolled, this sum was sufficient to afford a liberal education for each child in

the Chickasaw Nation. For many years previous to this time the money received from the sale of lands in Tennessee and Kentucky

had been used to educate the youth of their Nation. So when the Chickasaws established their constitutional form of government,

they were quite competent to administer it. This valu-

Page 375

able experience in government enabled a more intelligent participation in American life, which lay in the future. The Chickasaws,

since statehood, have contributed most effectively to capable leadership in the political life of the State of Oklahoma.3

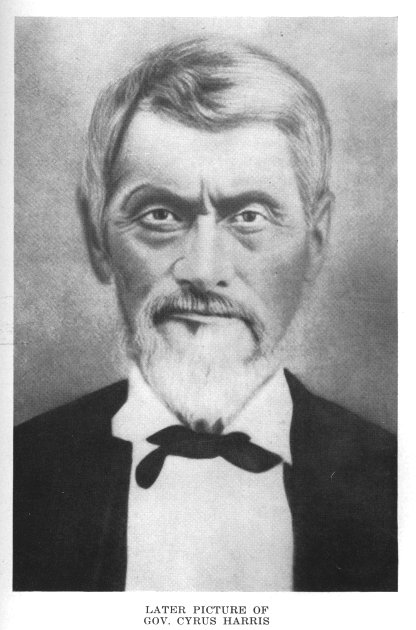

The administration of political affairs of the new Chickasaw Nation under its new constitution was initially undertaken by

Cyrus Harris,4 who became its first governor, in August, 1856. His background is one of more than passing interest.

The collapse of the Jacobite Uprising in Scotland, fomented by the Scottish adherents of James the Pretender, in 1715, and

the ensuing years of reprisal exacted by the English, influenced the emigration to America of many of the grim Highlanders.

The inflow continued for many years. The first contingent of these people to settle in Georgia arrived at Savannah, in January,

1736, and among these earliest arrivals was young Logan Colbert. He doubtless came with the party led by John Mohr McIntosh

which sailed from Inverness, Scotland, on October 18, 1735, on the ship "Prince of Wales" commanded by Capt. George Dunbar.

Soon after landing at Savannah, courageous young Colbert abandoned the white settlement, ventured to the far West and settled

among the militant Chickasaw Indians who then ranged along the eastern banks of the Mississippi from the mouth of the Ohio

to the vast stretches of the lower river. It was an adventurous undertaking and his life story, if known, doubtless

3Among whom should be mentioned the late Charles D. Carter, for many years a Congressman from Oklahoma; Reford Bond, Chairman

of the State Corporation Commission; Jessie R. Moore, a former Clerk of the State Supreme Court and today, a member of the

Board of Directors of the State Historical Society and its Treasurer; Douglas H. Johnston, Governor of the Chickasaws since

1898, (with the exception of the term that Palmer S. Mosley was chief); Judge Earl Welch, a Supreme Court Justice; W. C. Lewis,

United States Attorney for the Western District of Oklahoma; Ben Harrison, a Secretary of State; Otis Leader, a noted World

War veteran; and former Governors Lee Cruce and William H. Murray, who became members of the Chickasaw Tribe by intermarriage.

4The Indian Champion (Atoka, Indian Territory), April 18, 1885; H. F. O'Beirne, Leaders and Leading Men of the Indian Territory (Chicago, 1891), I, 209; H. B. Cushman, A History of the Choctaw, Chickasaw and Natchez Indians (Green. ville, 1899), 513 et seq. Under the new constitution the title of "Governor" was substituted for "Chief."

Page 376

would be one of dramatic interest. He seems to have cultivated a sympathetic understanding with the Indians, married into

the tribe and became a character of much prominence among them and a renowned leader in their wars against the French. The

descendants of Logan Colbert in Oklahoma today, recall with much pride, the emigrant Scotch lad of the early days of the eighteenth

century.5 He met a tragic death at the hands of a negro slave who was accompanying him on a trip back to Georgia.

Major William Colbert, a son of Logan Colbert, became a famous war chief among the Chickasaws and early in life took an active

part in the political affairs of the tribe. He represented his people at Washington, upon numerous occasions, and in the very

early days, was received by President Washington, in Philadelphia. At the solicitation of Washington he led a contingent of

Chickasaw warriors in support of Gen. Anthony Wayne at the battle of Fallen Timbers, Ohio, on August 20, 1794, against Little

Turtle and the Northwestern Confederation of Indians. Major Colbert served nine months in the 3rd Regiment of United States

Infantry in the War of 1812, concluding his military career by an effective participation in the war against the recalcitrant

Creeks. As a commissioner from the Chickasaws, he was a signer of the treaty of October 4, 1801,6 and the treaty at Washington, of September 20, 1816.7 By the terms of the latter treaty, he was granted an annuity of $100 for the remainder of his life and was also styled a

major-general. He also signed the Chickasaw treaty of October 19, 1818.8 The major signed these treaties by mark, which would indicate his lack of any scholastic training, although he is recognized

as a character of pronounced native courage, ability and fine judgment. Major Colbert married a Chickasaw Indian woman by

the name of Mimey and lived at Tokshish, Mississippi,

Page 377

some four miles southeast of Monroe, and doubtless was largely instrumental in securing the establishment of the celebrated

mission at that place. He was a contemporary of the famous Chief Piomingo of the Chickasaws, and passed away at an advanced

age, sometime shortly before the Chickasaw removal of 1837-8.

An interesting character among the Chickasaws in Mississippi was Mollie,9 daughter of Major William Colbert. As a young woman she married Christopher Oxbury, a mixed-blood Chero-

9The life story of Mollie Colbert, the attractive Indian princess daughter of Major William Colbert of the Chickasaws, is one

of romantic interest. After the death of Christopher Oxbury, her Cherokee husband by whom she had several children, she married

James G. Gunn, a wealthy English planter. Gunn was a native of Virginia, fought with the British in our war of the Revolution

and after the war removed from Viriginia to the remote edge of white settlement and located among the Chickasaw Indians and

in what is today Lee County, Mississippi. He never composed his disdain for the new United States Government and would suffer

no observance of the Fourth of July to be held upon his plantation, although he thoughtfully observed the birthday of George

III. He died in 1826. Rhoda, the only child of James and Mollie Gunn was famed as a celebrated beauty and of her engaging

qualities much has been written. Perhaps the story which is handed on down, of her romantic marriage to Humming Bird, a Chickasaw

warrior, is more or less legendary. From his home at Mill Creek, C. N., Gov. Cyrus Harris, on August 10, 1881, wrote an interesting

letter to Harry Warren of the Mississippi Historical Society in which he narrates many interesting details, some of which

divest the romance from this oft repeated story about the marriage of Rhoda. He says, "Molly Gunn, my grandmother, was the

wife of the old man James Gunn, who died rich, leaving one child, Rhoda. She (Rhoda) died two years ago, on Red River (Indian

Territory) at her half-sister's, who was my aunt, a full-sister of my mother and a half-sister of my Aunt Rhoda. My grandmother's

first husband, my mother's father, was a Cherokee, named Oxberry. After his death, she married old man James G. Gunn. Rhoda

married Samuel Colbert, a nice man, but they separated and she married Joseph Potts, a white man. He died during the Civil

War (1862) by taking strychnine by mistake. He died at my house. Aunt Rhoda had two sons living, Taylor and Joseph Potts.

Her first child by Sam Colbert was a girl named Susan. She married and went off and never was heard of since. Malcolm McGee

was my step-father. He had one daughter by my mother and named her Jane. My sister Jane married Robt. Aldridge, a white man

who lived at Tuscumbia, but after they came to this country (Indian Territory) he got so trifling she drove him off. He then

went to Texas and died. They had one daughter who is yet living. Jane afterwards married a nice gentleman by the name of William

R. Guy and soon after she and Mr. Guy were married they went after sister Jane's father, old man McGee, and had him with them

at Boggy Depot, Chickasaw Nation, but he, being very old, lived but a few months after getting there. I saw the old man die

and was at his funeral. Old man McGee was a little over one hundred years old when he died. He was a long time United States

Interpreter for the Chickasaws and it was said he could beat the Chickasaws talking their own tongue. Mr. and Mrs. Guy had

nine children when Mrs. Guy died at Boggy Depot. About a year after her demise, Mr. Guy died at Paris, Texas, being there

on a visit." Harry Warren, "Chickasaw Traditions, Customs, etc.," Mississippi Historical Society Publications (Oxford, 1898-1914), VIII (1908) 546 n.; Harry Warren, "Missions, Missionaries, Frontier Characters and Schools," loc. cit., 587-8. E. T. Winston, "Father" Stuart and the Monroe Mission (Meridian, Miss., 1927), 50-51.

Among the nine children of Mr. and Mrs. William R. Guy above mentioned were William Malcolm Guy, who was born at Boggy Depot,

on February 4, 1845, and was Governor of the Chickasaw Nation, in 1886-8; Cerena Guy, who married Ben W. Carter and became

the mother of Hon. Charles D. Carter, a former congressman; and Mary Angelina Guy, who married Capt. Charles LeFlore and became

the mother of Mrs. Lee Cruce, the wife of the second Governor of Oklahoma.

Mollie Gunn seems to have been a member of the Presbyterian Church at Monroe Mission, but the following disquieting notation

appears in the old church records: "April 5, 1834, the following persons having been under suspension from the privileges

of the church for a length of time and giving no evidence of repentance, but continuing impenitent, were solemnly excommunicated,

viz: Mollie Gunn, Nancy Colbert, Sally Frazier, James B. Allen, Benjamin Love and Saiyo." Her father, Major Colbert, also

appears to have run counter to church discipline as it appears from the same record, "September 7, 1834. Session convened

and was constituted by prayer. Mr. William Colbert, a member and an elder of this church, having been cited to appear before

the session to answer the charge of intemperance, appeared accordingly, and having confessed his sin, expressed deep contrition

for the same, and promised amendment; the session resolved that it is a duty to forgive him after requiring him to make a

public confession before the congregation and promising to abstain in the future. Concluded in prayer. T. C. Stuart, Mod.

Examined and approved by Presbytery at Unity Church, March 7, 1835." The old major passed away a year or two later. See Winston,

op. cit., 40-41.

It is of interest to know that the Chickasaws had no clans as did most of the other tribes, but were distinguished by distinctive

House names, the ancestry being traced back through the mother. Mollie Colbert and her descendants were of the House of Inchus-sha-wah-ya.

Page 378

kee, a proficient interpreter and a person of high standing among the Chickasaws. They lived upon her comfortable estate three

miles south of Pontotoc, Mississippi, where her daughter Elizabeth or Betty was born. Her interesting home stood upon an ancient

mound, the highest point in that part of the State, and surrounded by 1,000 acres of beautiful table-land. All of her children

were born there as well as her famous grandson, Cyrus Harris, who was born there on August 22, 1817. The identity of the father

of Cyrus Harris is somewhat confused. He is reputed to have been a white man by the name of Harrison, the name being subsequently

shortened to Harris. Elizabeth's marriage to him was of brief duration, as she soon left him and returned to the home of her

mother, where her son, Cyrus Harris, was born. The father declined to remove with the Chickasaws, at first, although he later

attempted to join his son in the old Indian Territory. Cyrus Harris declined to have anything to do with him. Elizabeth married

Malcolm McGee,10 very shortly but again returned to her mother at

10Malcolm McGee, of Scotch parentage who had recently emigrated from Scotland, was born in New York City about 1757, his father

having been killed shortly before, at the battle of Ticonderoga, in the French and Indian War where he fought with the Colonial

troops. While he was quite young, his mother removed to and settled on the north bank of the Ohio River, in southern Illinois,

at Ft. Massac, and immediately across the river from the Chickasaw country. McGee had no schooling, but served as an interpreter

among the Chickasaws, for forty years. It is said, "He assumed the Indian costume and conformed to all their customs except

their polygamy." He married Elizabeth, a daughter of Christopher and Mollie Oxbury as his second wife, about 1819, and had

one daughter, Jane. Shortly thereafter Elizabeth left him, taking the child with her. The mother later returned the child

and she was placed by McGee in the home of Dr. T. C. Stuart, to be educated at Monroe Mission. In 1849, Malcolm McGee removed

from Mississippi to the old Indian Territory, where he lived at the home of his daughter, Jane (Mrs. William R. Guy), at Boggy

Depot, and where he died on November 5, 1849. Cyrus Harris became the guardian of their minor children whom he reared and

educated. For further details, see Winston op. cit., 84 et seq., and Cushman, op cit., 509 et. seq.

Page 379

Pontotoc.11 Mollie sold her famous home about 1830, to Robert Gordon, who thereafter erected the spacious plantation home "Lochinvar"

upon the site and where his son, Col. James Gordon, afterwards a United States Senator from Mississippi, was born. After the

sale, Mollie removed with her children, including Elizabeth, to Horn Lake, in what is today DeSoto County, Mississippi, where

she passed away shortly before the removal of the Chickasaws, in 1837-8. Elizabeth removed in the party with her son, Cyrus

Harris, to the old Indian Territory, late in 1837, where she died some years later, at Mill Creek, at the home of her famous

son.

The educational advantages of Cyrus Harris were very limited. In 1827, he was sent to the Monroe Presbyterian Mission, of

which school Dr. T. C. Stuart was in charge. In the succeeding year, he was entered at a small Indian school in Giles County,

Tennessee, under the tutelage of Rev. William R. McKnight. He returned home, in 1830, and after a few years' residence with

his mother and grandmother, who were then living at Horn Lake,

Page 380

he made his home with his uncle, Martin Colbert, near the same place.12

The Chickasaw Indians, in 1835, began intensive preparations for their en masse removal to the West. A government land office had been established at Pontotoc and, through interpreters, the individual

land holdings of the Indians were being identified and immediately bought up by land speculators. Young Harris sought employment

at Pontotoc, as he spoke both Chickasaw and English with tolerable fluency. He first became engaged in the trading store of

Capt. John Bell, but later was used as a contact man by Captain Bell and Robert Gordon, who were jointly engaged in purchasing

lands from the Indians, who were about to remove to the West. The sale of these lands was practically completed in 1836, and

the Chickasaws began their final plans for the emigration. Harris became an interpreter at the numerous Councils which were

held and at which the details for removal were arranged.

Cyrus Harris with his mother, Elizabeth, left Horn Lake, on November 1, 1837, for Memphis, to join a party of the emigrants

led by A. M. M. Upshaw, the emigrant agent. Within the next few days they crossed the Mississippi and proceeded overland to

Ft. Coffee. He tarried for a brief two weeks in camp at Skullyville and in the following year settled on the Blue River, in

what is today Johnston County, Oklahoma. His initial years in the West were simple and unexciting, having those idyllic, pastoral

qualities so engaging to the Indian of that period. Early in life, he evidenced an interest in the political affairs of his

people, and in 1850 was dispatched as a delegate to Washington, in company with Edmund Pickens. Upon his return home, he disposed

of his place on the Blue and removed to Boggy Depot where he lived for about a year, after which he established his home on

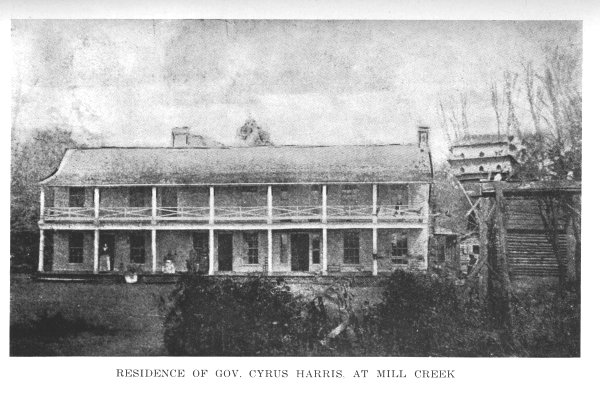

Pennington Creek, about one mile west of Tishomingo. He removed again in No-

Page 381

vember, 1855, to Mill Creek, northwest of Tishomingo, where he continued to reside until his death.

Cyrus Harris again was sent as a delegate to Washington, in 1854, and upon the adoption of the new constitution, in August,

1856, was chosen as the first governor of the Chickasaw Nation. In this memorable first election there were several candidates,

but when the results were totaled, it appeared that no one of the aspirants had secured a majority of the votes cast, and

as a consequence, the choice was delegated to the legislature, with the result that Cyrus Harris was chosen by that body by

a majority of one vote. The young governor organized the new government, served through the two year term and was succeeded

by Dougherty (Winchester) Colbert. He was reelected in the fall of 1860, but again was defeated by Dougherty Colbert, in August,

1862. These were the opening days of the Civil War and the Chickasaws were the first of the Five Tribes to evidence their

open preference for the Confederacy. Resolutions of secession from the Union were approved by Governor Harris, on May 25,

1861. An influencing factor in taking this action was the abandonment by the United States Government of Ft. Washita, thereby

leaving the Chickasaws at the mercy of the Plains Indians. It is said of Governor Harris that as he reviewed the Chickasaw

troops marching away to war, the tears ran down his cheeks as he stated that, "This was the first time in history the Chickasaws

have ever made war against an English speaking people." In the fall election of 1866, Cyrus Harris again was reelected as

governor and succeeded himself in 1868. His executive ability once more was recognized when he again was elected governor

of the Chickasaws, in 1872. He was chosen to the highest position among his people in the West, upon five different occasions,

which was a record to be unequaled among the Chickasaws. It was a marked evidence of the high esteem and regard in which he

was held by his people.

Page 382

A complete survey of the public life of Cyrus Harris, would involve a history of the Chickasaw Nation from 1856 to 1888. He

was in intimate touch with its political life during that period. They were the years of tragedy and of the reconstruction

after the Civil War. It was with unfaltering steps that he led his people through this crucial period. The matter of the establishment

of educational facilities received his marked attention. An appropriation of $2500 to repair the academies was approved by

him on September 18, 1872, and on September 21, 1872, he approved the establishment of a boarding school at Wapanucka.

The famous governor possessed a rare vision of approaching difficulties for his people which lay far in the years ahead. The

specter of the allotment of tribal lands in severalty and the destruction of their communal life, had not, as yet, engaged

the thought and attention of the Indians. Governor Harris saw its approach and in his message to the legislature on September

2, 1872, sounded a note of warning in courageous words, "Before closing my brief address, I wish to detain you a few moments

on a subject of much importance. Although it is unpopular among our people and I must candidly confess that I, as one interested,

could not consistently give my consent to its approval, had we any shadow of remaining as an independent nation, holding our

lands in common. But can we, with any degree of certainty, continue the hope of holding lands in common, when railroad agitators

and land speculators are using all available means to open our country to the settlement of the whites. Notwithstanding the

Indian policy of the President of the United States to consolidate and settle in the Indian Territory, all Indian tribes under

the jurisdiction of the United States, we hear, in the halls of Congress, the advocation of extending Territorial Government

over the Indian country. From this we must suppose that we are liable at any moment to be robbed of the rights to our lands.

The country we occupy, we hold under a patent granted by the United States to the Choctaw

Page 383

Nation, in which the Chickasaws have, by the consent of the former, acquired an interest...But we are told by these that seem

to know, that land held in common, does not meet with the approbation of the Government of the United States, although, by

that Government, we are promised protection against the inroads of any other tribe and from the whites; and also agreed to

keep us without the limits of any State or Territory. But can we depend on this much longer in consideration of the great

railroads and border states banded against us? If we can, I again say, let us live in peace, holding our lands as in the days

of old. Well, then under these circumstances, let us look a little ahead and perhaps we may imagine that something more than

usual is approaching.... There are many matters which could be enumerated to show why it is necessary to prepare for the approaching

events. Well, then, under all these circumstances, should we undertake to continue the holding of all our lands in common?

Or should we make an effort to divide all of our lands severally, as provided for in Articles 11 and 33 of the Treaty of the

28th of April, 1866? This is an important question and should be well considered and should not be delayed. By the plan latterly

mentioned, if successful in carrying into effect, will at once put a check upon the ingress of those who seek the downfall

of our nationality."13 His vision was thirty years ahead of what actually occurred but his surmises were accurate. The governor evidenced a distrust

of the Government in fulfilling certain of its treaty engagements, against which evasions the Indians had no recourse. Through

his firm reconstruction policy, the former slaves of the Chickasaws were denied tribal membership, but the adventurous whites

who were drifting into the Territory presented a more serious problem, but one which he doubtless felt was capable of solution.

His earlier experiences in Mississippi with the land speculators provoked grave apprehensions in the heart of Governor Harris,

as to consequences, if the influx of white settlers should assume

Page 384

proportions. The Chickasaw legislature, in 1876, rather complicated the situation by admitting the intermarried whites into

full tribal membership. An economic advantage thus was created and eagerly sought by designing white men. Marriage was easily

accomplished by the adventurous white man and thereby his tribal membership became fixed.14 Such marriages were not, of necessity, permanent and were easily dissolved by agreement and decree of divorce granted before

a court of competent jurisdiction and the white man was then at liberty to marry a white woman who at once acquired the tribal

status of her husband. Governor Harris in his message to his legislature on September 2, 1872, touched upon this question

in language which disclosed his complete understanding of the situation, "I would also call your attention to the mode and

manner in which the bonds of matrimony are dissolved. The records of the Courts of the Nation show that nearly all the divorces

granted are to parties who mutually agree to a dissolution, many of whom, perhaps, could have lived together in peace the

remainder of their lives but for the easy matter of procuring a divorce by mutual consent. I would recommend that there be

fines imposed in all cases of divorce by mutual consent, or, repeal the law authorizing divorce in toto. By repealing the divorce law, you put a check upon all who only marry for a foot-hold in the Nation, caring but little for

the women whom they take for wives."15 The advent of the whites in succeeding years and their participation in tribal government began to imperil the political

life of the Nation, as the native Indian understood it. Governor Harris was a progressive leader, but none the less a staunch

friend of the full-blood members of his tribe and as equally devoted to their interests. In

Page 385

his campaign for a reelection in 1874, these people supported B. F. Overton, who was elected governor, and reelected in 1876.

The concluding gesture of Governor Harris was made in the fall of 1878, when his candidacy for governor was inspired by his

legion of friends throughout the Nation. He was supported by the progressive mixed-blood and white citizens and probably received

a majority of the votes cast and should have been inducted into the governorship. His election was declared by the legislature

and on September 23rd, he took the oath of office. On the following day, a somewhat disorganized session of the lower house

of the legislature, acting under the inspiration of Governor Overton, reversed the former action, went through the form of

throwing out a sufficient number of votes cast for Harris and declared the election of B. C. Burney, by a majority of five

votes. The campaign had been tense but the aftermath was more so.16 Great dissatisfaction prevailed and threats of violence presaged armed strife. Governor Harris immediately withdrew from

the contest, conceded the election of Governor Burney and further trouble was averted. It was a patriotic finale to his long

and faithful service as a trusted leader of the Chickasaws. He gracefully retired to his home at Mill Creek, and announced

the conclusion of his public career. His interest thereafter, in the political concerns of his people, was not entirely negligible

nor passive. He emerged from his retirement and gave a militant support to William M. Guy, his nephew, who was elected governor

of the Chickasaws in the fall of 1886, on the Progressive ticket. The lines of cleavage between the "white" Indians and the

more conservative full-bloods, was clearly defined during the campaign with William L. Byrd representing the latter. The adopted

and intermarried whites were disfranchised by act of the legislature on April 8, 1887, and at the ensuing election of August,

1888, Byrd defeated Governor Guy, who was a candidate for reelection. The full-bloods triumphed again

Page 386

in 1890, when Byrd, who strove vainly to preserve the political life of the tribe for the native Indians, was reelected. But

the influence of the whites soon thereafter began to evidence itself and gather control. Rigor mortis already had set in on the political and communal life of the Chickasaws and the time was soon to arrive when the Government

was going to probate the estate and distribute the proceeds. Governor Harris, who had so accurately presaged the finale, passed

away on January 6, 1888, at his home at Mill Creek, in what is today Johnston County, Oklahoma, where he is buried.

Cyrus Harris was a farmer and, to some extent, engaged in the cattle business, which was an overshadowing industry during

that period. He was married three times. His first wife was Kizzia Kemp, sister of Joel Kemp. Upon the death of Tenesey, his

second wife, he married Hettie Frazier, a widow of Ishtehotobah, the venerable and beloved King of the Chickasaws.

No character during his generation impressed so strongly and effectively, the political life of the Chickasaw Nation as did

Cyrus Harris. Although practically devoid of trained educational advantages, nature had endowed him with unusual ability and

powers of discernment. He was a progressive and despite his early experiences in Mississippi, seemed in his later years to

compose his vision to the influence of the white members of the tribes, nevertheless he was unfaltering in his fidelity to

the best concerns of his people as he understood them. His high, patriotic character is evidenced in his generosity and self-sacrifice

in withdrawing from the post election troubles of 1878. Cyrus Harris was a character of the highest integrity and ever will

adorn the pages of Chickasaw Indian history, as one of its outstanding leaders.

Return to top

Electronic Publishing Center |

OSU Home |

Search this Site

|