In 1985, Jello Biafra, the singer of the punk band the Dead Kennedys, came across a painting by the Swiss surrealist artist H. R. Giger in a copy of Omni magazine. “I was absolutely floored,” Biafra says in a new interview (audio) posted on the website of his record label, Alternative Tentacles. “Best stuff I’d seen since Bosch.”

The encounter of the two iconoclastic artists led to one of the opening salvos in the 1980s culture wars—and an emotionally satisfying victory of artistic freedom over censorship, even if it turned out to be only a pyrrhic one.

When Giger died last week at 74, after a fall, he left behind a trail of images that linger in the mind much like the nightmares that troubled his sleep. His visual style, which mixed gothic decay with serpentine futurism, left a deep impression on anyone who experienced it in the 1979 sci-fi classic Alien (for which he won an Oscar for visual effects). But Giger also had a powerful effect on visual culture in an entirely different arena, far from multimillion-dollar Hollywood franchises.

His artwork became the center of a legal case around the Dead Kennedys’ third album, “Frankenchrist,” after Biafra inserted a poster of Giger’s “Landscape XX” (also known as “Penis Landscape”) in the record sleeve. “This picture is like Reagan America on parade,” Biafra recalls thinking the first time he saw it.

Biafra initially wanted to use “Landscape XX“ as a gatefold cover for the album, with “Frankenchrist” written in candy-cane lettering. But making the record retail-friendly by wrapping it in colored plastic proved too expensive, and when the distributor and other band members objected to using the image openly, he decided to include it as a poster instead. The album had a sticker on the cover, warning that “some people may find [the poster] shocking, repulsive, or offensive. Life can sometimes be that way.”

“Frankenchrist” was released in October of that year—a spectacularly bad time, as it turned out, to test the limits of free speech in America. The US Senate was in the midst of hearings on “potentially offensive content” in popular music. Months earlier, the Parents Music Resource Council, or PMRC, cofounded by Tipper Gore (then the wife of US senator and future vice president Al Gore), had succeeded in pressuring record companies to add warning labels to albums by artists such as Prince and Twisted Sister.

But, Biafra recalls in last week’s interview, the movement had not yet coalesced behind an obscenity prosecution. “They needed a pigeon,” he says. “They needed someone to actually charge with a crime.”

That changed when a 14-year-old girl bought a copy of “Frankenchrist” at a store in California’s San Fernando Valley as a birthday present for her 11-year-old brother. Though she later said that she found the Giger poster “gross…but not harmful,” her mother lodged a complaint with the state’s attorney general. A few months later, nine police officers stormed into Biafra’s apartment in San Francisco and his record label’s offices, seizing copies of the album and demanding to know where Giger lived.

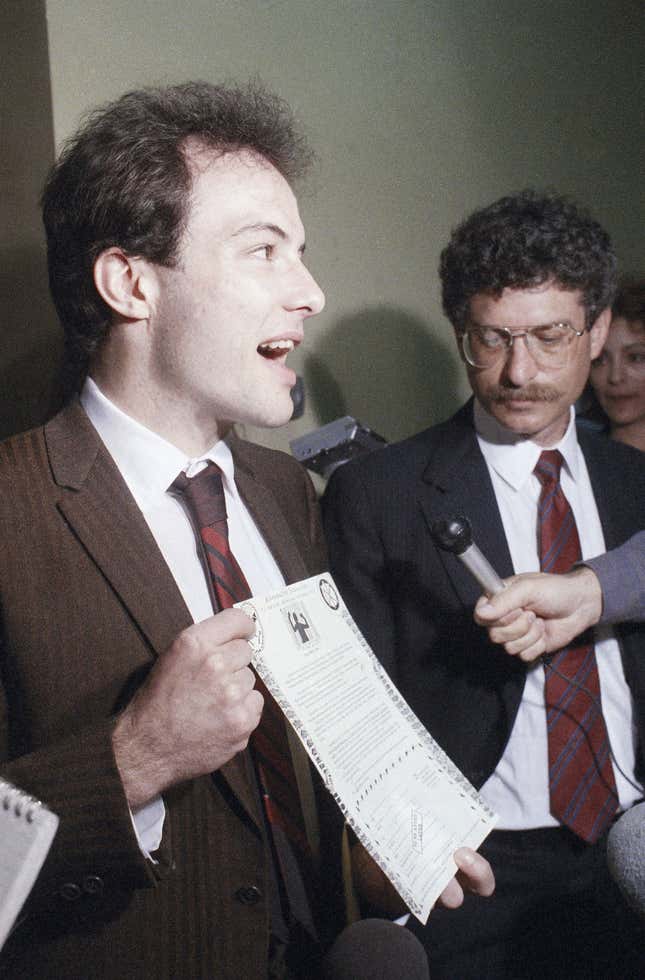

Biafra and Michael Bonanno, the general manager of Alternative Tentacles, were arrested and charged with distributing harmful material to a minor, under California Penal Code section 313.1, which carried a possible one-year jail term and $2,000 fine. (Similar charges against the album’s distributors and pressing plant were quickly dropped.) “We were the first people to be prosecuted over an album in American history,” Biafra says.

In court, the prosecutor, Michael Guarino, called the poster “pornography” and compared Giger to Richard Ramirez, the serial killer. “Giger sees people the way Ramirez sees people,” he said. “They are objects to hurt. They are not human.” The defense argued that “Landscape XX,” which had hung in Vienna’s Museum of Modern Art and the Bronx Museum, was ugliness as social commentary, not obscenity. In the end, their argument carried the day. The jury deadlocked 7-5 in favor of acquittal, and the judge declared a mistrial. A few of the younger jurors asked Biafra to autograph the poster. (It was no longer included in the record after the trial, though it was available long afterward by mail order from Alternative Tentacles—with proof of age.).

The case reverberated for years. “If any of us had been convicted, there would have been a precedent set where even an artist or a crew member working on a project that someone deemed obscene would be responsible for the whole project,” Biafra told the Miami Herald after the trial. Even though Biafra was acquitted, many chain stores still pulled his band’s—and his label’s—records from their shelves. The trial was twice re-argued on the daytime talk show Oprah, with Biafra and Gore as sparring partners. And Giger’s work became a banner to raise in the culture wars’ skirmishes over censorship.

Though Giger didn’t appear at the trial, Biafra got to know the Swiss artist after the case, he recalls in the interview. They met in New York City at an opening of Giger’s artwork, where the theatrically gruesome metal band Gwar made a surprise appearance in full costume. (Already nervous about showing Giger’s work, the gallery owner fled, Biafra remembers.) Later, Biafra visited Giger at his home in Zurich. Inside, the walls were all black; outside, amid the weeds, stood the artist’s sculptures, with mushrooms growing from their backs. A model train passed straight through the house in a tunnel that “of course, was a thinly disguised vagina,” Biafra says.

Meanwhile, the prosecutor had a surprising change of heart. ”About midway through the trial we realized that the lyrics of the album were in many ways socially responsible, very anti-drug and pro-individual,” Guarino told the Washington Post in 1997 (paywall). “We were a couple of young prima donna prosecutors.” He was even more pointed eight years later in an interview for the public radio show This American Life: “I just felt I was on the wrong side of history.”